|

Title: Waits/ Wilson Woyzeck Promo Interview Source: Promo interview with Robert Wilson and Tom Waits, by Peter Laugesen. Transcription by Keith A. Durrans. Excerpts as published in 2002 Woyzeck theatre program. Excerpts also published as "The Poor Soldier Gets Those Proletarian Lovesick Blues" (The Independent. November 19, 2000) Date: Betty Nansen Teatret, November 2000. Key words: Robert Wilson, Woyzeck, Theatre, Creative process Picture: Promo interview screenshot. Tom Waits and Robert Wilson, 2000 |

Waits/ Wilson Woyzeck Promo Interview

Waits: We met in New York City. My wife and I had written a play called "Frank's Wild Years"(1). We asked Bob if he would direct the play, and one thing led to another. We didn't actually do that project, but we went on ultimately to do two other projects together. We did "The Black Rider" and "Alice", both with the Thalia Theatre(2). I agree that we're different men with different approaches to work with. The fact is, I think that if two people do know all the same things, then one of them becomes immediately unnecessary. There's something that I deeply respect about Bob's world view, it's sensitised me for the way that I think that now I see the world. I never noticed furniture before and now I notice chairs all over the world(3), everywhere I go. The key word really is `play', because I really get a lot of pleasure out of working with Bob and plumb the depths of myself, I think in a lot of ways. You lose track of the time. I mean how often do you get to go into a room and tell somebody about how the light should be, how the floor should be and everything you should hear and what you want everyone to say. It's ' great pleasure to go into a room where you can have something to say about all those details. So a true pleasure to work together. What with you Bob?

Wilson: Well ... I realised when Tom and I first met that I wasn't so aware of his work. Then I heard him playing the piano and I immediately was touched by it. When I heard Tom touch the keys somehow he touched me, he got me. From the beginning there was this attraction. I can't explain it because it's so complicated . . . it's funny, it's sad, it's touching, it's noble, it's elegant. It's his signature, it's something personal. As Tom said we're different and I think that that's the attraction. They say opposites attract and somehow we complement each other, but there's a lot of overlap too. He can talk to me about direction or the look of a stage, or a character, the development of a piece, and Tom doesn't mind if I say something about the music or the sound. There's a real trust, and I think that's very rare that you can trust each other. In that way it's a real operation. When I look back at "The Black Rider", I don't remember who did what, sometimes it was like it just happened.

Waits: Well I think Bob's in charge.

Wilson: I think there's no one in charge. I think my responsibility is to provide a space where I can hear Tom's music. Can I make a picture, a colour, or a light, or setting for where we can listen to this music. Often when I go to the theatre I find it very difficult to listen, the stage is too busy or things are moving around too much and I lose my concentration. If I really want to concentrate deep, I have to close my eyes to hear. I try to make a space where we can really hear something, so what we see is important because it helps us to hear. I think that's one of the reasons I'm attracted to Tom; his understanding of his body and that his body is his resource, his movements, how the music comes from that .... It's deeply rooted in the body, and so often I feel that the work doesn't get deep inside the bodies, but I think in Tom somehow it does. His feet are on the ground.

Waits: I think all things really do aspire to this whole condition of music. And Bob has a way of seeing and hearing - and you do start hearing and seeing really extraordinary things in very ordinary places if you just close one eye or tilt your head. Well the thing about working with Bob that you notice immediately is that he has a tremendous amount of leadership quality and that is something that comes immediately evident.

Wilson: It's really surprising though, because all the time I was in school I was almost terrified to speak. I would come home from school, go in my room, close the door, lock the door and stay alone ... never any leadership quality. I always feel like I'm six years old when I have to get up and tell somebody what to do, but then somehow it's the other side of you. It surprises myself that sometimes I can say OK now everyone be quiet or shut up. The thing that's great about Tom is that he of course writes songs for himself but he's able to write music and other people can sing it. You can look at the pieces that I've done with Tom, they can stand on their own without Tom having to sing the songs. I think that was a great test for Tom that he came in as a composer, can find a voice for other people or his music could be transposed to other singers, other personalities whose voices are very different to his. In that sense he's a real composer.

Waits: Yeah it's a challenge, it's a real challenge, I was wondering if I was going to be up for the challenge. It was sometimes where I was real cold, but it's ultimately very satisfying. But like I said it's hard sometimes when somebody else is doing your song. What I like about Bob is that if he's telling somebody how to move on-stage he'll come on up and he'll show them how to move, he'll do this most spontaneous and mystical physical movement. That is captivating and then he'll go like this and ask them to try on the same movements. They're never completely the same, but they break eggs for the cast each time he does that. And sometimes you can do that with the songs as well; you can sing it for them. Technique is not important, emotional telegraphing and truth is what is important and it requires no technique except emotional technique, but no actual, as to how many notes you can hear or how fast you can get there and how you fly it off those and the other notes, it doesn't really matter. That's what everybody wants to do when they come to the theatre they want to connect.

Wilson: That's the most important thing, if you can connect with the public. I think you start thinking about a lot of ideas then you dig deep down into the piece and gets very complicated. In the end you want to come back to the surface and sort of forget about everything and just sit there and experience it. So every night you can experience it on a different level or different wave that you don't want to fix any one idea ... oh well this is this or this is that. He is crazy, well maybe he's not crazy, maybe it is love, maybe it's not love... But in order to get there, to get the surface sort of simple and mysterious I think you have to dig down and find out all these different facets to these characters and this story so it is multi-faceted. But in the long run I hope it could be very simple and then I forget about all of those stories. Then I find other stories, so you get that surface to resonate, to kind of go in there and somehow fight with boxing gloves sometimes, it'll come to you or you'll go to it. It's like letting a child go. You watch him grow and walk on its own feet and there comes a time where you realise as a director, or someone who's helping make it that you no longer can do it and you've got to let these kids do it ... you just sit back and look at it. I think abstractly. I can just listen to the colour of the voice. Theatre is something plastic- make this quicker or make this slower or more interior, deeper... You can tell if the actors are thinking too much, if they're forcing an idea. Often you feel like it's blocked in the head. Open it up, receive, let it come to you.

Waits: I told someone the other day that the song doesn't begin at the beginning of the song. You don't want to feel the sense of stopping and then planting your feet, looking up to the balcony, throwing your head back and starting a song. You really do want to kind of create a condition of music that starts at the beginning of the play, or it starts in the lobby, so that it's all music really - what you're seeing and what you're feeling and what you're hearing.

Wilson: But for me I think it's all music in a sense of the deeper emotional presentation is in the music. Somehow it all has to be about a truth. I touch this glass and it's cool; that's truth. I touch my forehead and it's warm; that's truth, I don't have to express it. Somehow your feeling is your expression. So if you're just speaking the text, or if you're singing it, whatever, you don't really have to express it, your feeling is your expression. That is about truth.

Waits: You really have to give it away and at the same time you really are kind of spotting somebody who's on the trapeze. You can't tell them to get down and let you up there so you can show them how to do it. You kind of talk them through it or want to say the right things. You want to be able to have them retain their confidence and at the same time be able to receive new ideas. Those are sometimes two mutually exclusive things. Some people take lecturing very well and others just want you to go away and let them do it the way they want to do it. It's difficult so you learn by doing. It's like Bob was saying -you're making all of these discoveries, sometimes you reach to pull out the carrot and you only get the top, sometimes you dig for hours and no water. But the deeper that you go in the work the deeper the experience will be for the audience. I mean ideally that's what we're all trying. There's always surprising things that you didn't even know were in the play. Somebody comes and tells you something after it's started and you just kind of nod and say: I don't remember anything about that in the play. So we all have a 360 view or beyond that really. It's hard to describe how you do what you do. I collaborate on the music with my wife, Kathleen Brennan. I guess starting really is the hard part. I didn't know the story and had to find out all about it. In some ways it's like writing music for a murder mystery and a children's story at the same time. It's real tragedy, but at the same time it's a great story. You don't really start in the beginning. You start somewhere in the middle and split off and half of you goes down this way back to the beginning and the other of you goes off towards the end. I'm not sure exactly how we collaborate on music. Sometimes we start with titles. Kathleen will have a series of titles, and sometimes that's all you need is the title and you begin from there and the title itself stimulates ideas. And a lot of times we come here to the theatre and we're sitting out in the dark and Bob's doing something on stage an idea for a song will come if you're in the right condition for it. And with Bob you always have to be ready to improvise, which is a really great muscle to develop, something that a lot of people stop doing when they grow up and the good part about working here is that you get to stay in shape using your imagination all the time. Bob will say - give me something here, we need something here, we need some music right now, just go down there and... It's really as simple as that, learning how to create on the spot and Bob really gives you a chance to do that. And I guess that's why it's so compelling to work here in this way.

Wilson: Actually we don't talk a lot about it beforehand. Often I find if I talk too much about a piece beforehand I go to rehearsal and I am trying to make in the rehearsal what I've been talking about instead of letting the piece talk to me. So if you go there and look at it and try to respond to it. I don't know, it's always better to just do it. Like Tom said I don't know how you do it, but you learn to walk by walking and you can talk about it all you want but you've got to get out there and do it. So you just go and do something. Pretty much we start with a blank canvas or blank book and start sketching it out. When I first came to Europe to work I was working in Germany and I found it so strange that the actors had been in rehearsal for three months and they had been sitting at table and reading books and talking about the production. I thought - how could they read books for three months and still talk about it? I'd just get up and do it. The German actors found it very difficult because they wanted to talk about it first and have some ideas before they get up and do it. As Tom said it's always difficult to get started, but once you do just something, anything and then look at that and let that talk to you and then say let's do the next thing, I'll let the next thing happen. One way of directing is for me, writing a piece or creating a work by doing it and not sitting in a room talking about it, or at a desk writing something or making drawings, but actually getting in the space and seeing the actors; listening to the actor; looking at their body; hear the kind of sounds they make and let that talk to me and give me the direction of where to go. I, in the late sixties began working in formal proscenium theatres, and I know at that time it was a bit strange. There was an exhibition at the Whitley museum - "All Against Illusion"- well that was the sixties, and I was fascinated by illusion. Nevertheless I came from this period. I wanted to put it inside of a box and look at it 2-dimensionally and then I became more interested in formalism and the kind of distance of looking at things. The kind of freedom that one could have and that one was sitting in the audience, one was free to imagine and think whatever. It was not coming out of what the popular theatre was, which were the psychologic, naturalistic theatre groups coming from a more artistic background. I think without John Cage, Alan Caprow, Robert Morris and Rauschenberg I probably couldn't have been doing what I was doing, but I took it and went somewhere else with it. My work definitely came from those roots. Also from a dance-orientation, although the work wasn't so much dance and then again in some ways it is. Martha Graham said that for her all theatre was dance and in some ways I feel the same way, we're always dancing, it's always movement. So I usually start with the body first, with the movement first and later let the other things come.

Waits: You have to have kind of an innocent bravery because, like for example on this, trying to get started just looking for songs. Kathleen said - well it's a circus story really. You know it starts with the Ferris wheel and the whole thing and this gal Marie is a Coney Island baby(4), and so we started there. And she had this beautiful melody on the piano, and it was like the way a kid would play the piano and when I heard it I said, god that is just so simple and so beautiful, and I hung onto it and put it onto a tape recorder and I carried around. And now it's the opening melody in the story. It's the first thing you hear, what sounds like a child's piano lesson and it really works. So I think it's hard to say where ideas come from. I think you just have to be ... we were talking earlier, sometimes you scratch and you scratch and you can't find any seeds and a moment later there isn't enough pots and pans to catch it in. The beauty of that is that it could be a very ordinary thing that you get an idea from. Something falls, a pigeon flies in or you hear a siren. The other night when we were playing in here and we heard a siren went by the theatre and I thought for a moment it must be part of the sound department's ideas. Bob must have told somebody that I want a siren right here, but of course it was just something that happened. That type of thing happens all the time and that's what I love about doing this is - that there is a place where life overlaps.

Wilson: What's great about Tom too is he's never afraid to leave his mistakes. A lot of times we waste time trying to cover up our mistakes.

Waits: I guess you could also say there are no mistakes really. I mean there are no mistakes, in music there are no mistakes. It all has to do with how you resolve a particular problem that you're trying to solve in a piece of music and a lot of breakthroughs come through mistakes.

Wilson: To me one of the attractions of this play is that it's not dated. I mean who would ever think that this was a play from the 19's Century? It's much more contemporary modem than most modern plays. These big sort of blocks of architecture, construction. All of the contemporary playwrights I can think of are nowhere near as modem as this - it's classical but it's very modem. It's not timeless but it's full of time. It's a classical construction because his mind was thinking in a very classical, structural way. 500 years from now this'll still be interesting because there's no shit, there's no garbage. There is like this brick is here, this brick is here, this brick is there and that brick is there. And it holds up, it stays together. It's structurally very soundly constructed. And you don't get involved with unnecessary things like hology and all these other things, it's very direct. And at the same time it's about the mysteries of life - something that's very concrete and something that's not at all. He must have been a genius of his age to construct these few works that he did.

Waits: Well you know with stories the hard part of getting the truth out of anybody is that the people who really know what happened aren't really talking and the people who don't have a clue are diving across the table for the microphone. And who knows what really happened in the actual story, it really doesn't matter anymore because it's now a story. And once something becomes a story it's like a hammer or it's a tool or it's a vehicle. It deals with madness and children and obsession and murder-all the things that we care about and care about as much now as we did then. It's wild and sexy and curious and catches your imagination and makes you wonder about the people in it and it makes you reflect on your own life. So I guess those are all the things you want from a story and find them interesting 500 years later. The first thing that you realise, and it's widely talked about, is that it's a proletariat story. A story about a poor soldier who is manipulated by the government and has no money, is used to experiment on and slowly becomes mad. I guess if they had anti-depressants in those days they could have straightened him right out.

Wilson: It's also a love story. I haven't figured out how to do it and don't know how successful we'll be in doing it. It's a very strange love story. There's Marie and Woyzeck standing there both looking straight ahead. These two people are somehow separate and together.

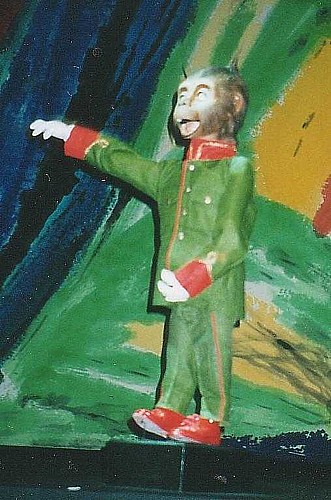

Waits: No more writing the songs for other singers. My voice is going to be the voice of the monkey at this point(5).

Wilson: I've got a little monkey in this play and that's Tom.

Waits: I'll be embodied somewhere.

Wilson: He's right down front too.

SOMETIMES YOU REACH TO PULL OUT THE CARROT AND YOU ONLY GET THE TOP

Excerpt from Peter Laugesens interview with Robert Wilson and Tom Waits, Betty Nansen Teatret, November 2000.

Edited and translated by the editors of the Woyzeck 2002 program.

Why Woyzeck?

Waits: Woyzeck deals with madness and children and obsession and murder - all the things that we care about. It's wild and sexy and curious and catches your imagination and makes you wonder about the people in it and it makes you reflect on your own life. So I guess those are all the things you want from a story and find them interesting 500 years later. The first thing that you realise, and it's widely talked about, is that it's a proletariat story. A story about a poor soldier who is manipulated by the government and has no money, is used to experiment on and slowly becomes mad.

Wilson: To me one of the attractions of this play is that it's not dated. I mean who would ever think that this was a play from the 19th Century? It's much more contemporary modern than most modern plays. All of the contemporary playwrights I can think of are nowhere near as modern as this - it's classical but it's very modern. It's not timeless but it's full of time. It's a classical construction because his mind was thinking in a very classical, structural way. 500 years from now this'll still be interesting because there's no shit, there's no garbage. There is like this brick is here, this brick is here, this brick is there and that brick is there. And it holds up, it stays together. It's structurally very soundly constructed. And you don't get involved with unnecessary things, like psychology and all these other things, it's very direct. And at the same time it's about the mysteries of life - something that's very concrete and something that's not at all. Georg B�chner must have been a genius of his age to construct these few works that he did.

Waits: Well you know with stories the hard part of getting the truth out of anybody is that the people who really know what happened aren't really talking and the people who don't have a clue are diving across the table for the microphone. And who knows what really happened in the actual story, it really doesn't matter anymore because it's now a story.

Wilson: It's also a love story. I haven't figured out how to do it and don't know how successful we'll be in doing it. It's a very strange love story. There's Marie and Woyzeck standing there both looking straight ahead. These two people are somehow separate and together.

Where do ideas come from?

Wilson: I think you start thinking about a lot of ideas then you dig deep down into the piece and (it) gets very complicated. In the end you want to come back to the surface and sort of forget about everything and just sit there and experience it. It's like letting a child go. You watch him grow and walk on its own feet and there comes a time where you realise as a director, or someone who's helping making it that you no longer can do it and you've got to let these kids do it ... I, in the late sixties began working in formal proscenium theatres, and I wanted to put it inside of a box and look at it 2-dimensionally and then I became more interested in formalism and the kind of distance of looking at things. The kind of freedom that one could have and that one was sitting in the audience, one was free to imagine and think whatever. It was not coming out of what the popular theatre was, which were the psychologic, naturalistic theatre groups coming from a more artistic background. It also came from a dance-orientation, although the work wasn't so much dance and then again in some ways it is. Martha Graham said that for her all theatre was dance and in some ways I feel the same way, we're always dancing, it's always movement. So I usually start with the body first, with the movement first and later let the other things come.

Waits: It's hard to describe how you do what you do. I collaborate on the music with my wife, Kathleen Brennan. Sometimes we start with titles. Kathleen will have a series of titles, and sometimes that's all you need is the title and you begin from there and the title itself stimulates ideas. Or Kathleen had this beautiful melody on the piano, and it was like the way a kid would play the piano and when I heard it I said, god that is just so simple and so beautiful, and I hung onto it and put it onto a tape recorder and I carried it around. And now it's the opening melody in the story. It's the first thing you hear, what sounds like a child's piano lesson and it really works. And a lot of times we come here to the theatre and we're sitting out in the dark and Bob's doing something on stage an idea for a song will come if you're in the right condition for it. And with Bob you always have to be ready to improvise, which is a really great muscle to develop, something that a lot of people stop doing when they grow up and the good part about working here is that you get to stay in shape using your imagination all the time. Bob will say - give me something here, we need something here, we need some music right now, just go down there and... It's really as simple as that, learning how to create on the spot. It can also be a very ordinary thing that you get an idea from. Something falls, a pigeon flies in or you hear a siren. That type of thing happens all the time and that's what I love about doing this is - that there is a place where life overlaps.

Wilson: Actually we don't talk a lot about it beforehand. Often I find if I talk too much about a piece beforehand I go to rehearsal and I am trying to make in the rehearsal what I've been talking about instead of letting the piece talk to me. So if you go there and look at it and try to respond to it. I don't know, it's always better to just do it. Like Tom said I don't know how you do it, but you learn to walk by walking and you can talk about it all you want but you've got to get out there and do it. So you just go and do something. Pretty much we start with a blank canvas or blank book and start sketching it out. When I first came to Europe to work I was working in Germany and I found it so strange that the actors had been in rehearsal for three months and they had been sitting at table and reading books and talking about the production. I thought - how could they read books for three months and still talk about it? Id just get up and do it. The German actors found it very difficult because they wanted to talk about it first and have some ideas before they get up and do it. One way of directing is for me, writing a piece or creating a work by doing it and not sitting in a room talking about it, or at a desk writing something or making drawings, but actually getting in the space and seeing the actors, listening to the actor, looking at their body, hear the kind of sounds they make and let that talk to me and give me the direction of where to go.

How do you collaborate?

Waits: We met in New York City. My wife and I had written a play called Frank's Wild Years. We asked Bob if he would direct the play, and one thing led to another.

Wilson: When Tom and I first met that I wasn't so aware of his work. Then I heard him playing the piano and I immediately was touched by it. When I heard Tom touch the keys somehow he touched me, he got me. From the beginning there was this attraction. I can't explain it because it's so complicated ... it's funny, it's sad, it's touching, it's noble, it's elegant. It's his signature, it's something personal.

Waits: I agree that we're different men with different approaches to work with. The fact is, I think that if two people do know all the same things, then one of them become immediately unnecessary.

Wilson: We're different and I think that that's the attraction. They say opposites attract and somehow we complement each other, but there's a lot of overlap too. He can talk to me about direction or the look of a stage, or a character, the development of a piece, and Tom doesn't mind if I say something about the music or the sound. When I look back at The Black Rider, I don't remember who did what, sometimes it was like it just happened, There's a real trust, and I think that's very rare that you can trust each other.

Waits: The key word really is 'play', because I really get a lot of pleasure out of working with Bob and plumb the depths of myself, I think in a lot of ways. You lose track of the time.

Wilson: I think my responsibility is to provide a space where I can hear Tom's music. Can I make a picture, a colour, or a light, or setting for where we can listen to this music. Often when I go to the theatre I find it very difficult to listen, the stage is too busy or things are moving around too much and I lose my concentration. If I really want to concentrate deep, I have to close my eyes to hear. I try to make a space where we can really hear something, so what we see is important because it helps us to hear.

Waits: Bob has a way of seeing and hearing - and you do start hearing and seeing really extraordinary things in very ordinary places if you just close one eye or tilt your head. Well the thing about working with Bob that you notice immediately is that he has a tremendous amount of leadership quality and that is something that comes immediately evident. There's something that I deeply respect about Bob's world view, it's sensitized me for the way that I think that now I see the world. I never noticed furniture before and now I notice chairs all over the world, everywhere I go.

Wilson: It's really surprising though, because all the time I was in school I was almost terrified to speak. I would come home from school, go in my room, close the door, lock the door and stay alone ... never any leadership quality. I always feel like I'm six years old when I have to get up and tell somebody what to do, but then somehow it's the other side of you. It surprises myself that sometimes I can say OK now everyone be quiet or shut up. The thing that's great about Tom is that he of course writes songs for himself but he's able to write music and other people can sing it. You can look at the pieces that I've done with Tom, they can stand on their own without Tom having to sing the songs. I think that was a great test for Tom that he came in as a composer, can find a voice for other people or his music could be transposed to other singers, other personalities whose voices are very different to his. In that sense he's a real composer.

Waits: Yeah it's a challenge, it's a real challenge, I was wondering if I was going to be up for the challenge. It was sometimes where I was real cold, but it's ultimately very satisfying. But like I said, it's hard sometimes when somebody else is doing your song. You really have to give it away and at the same time you really are kind of spotting somebody who's on the trapeze. You can't tell them to get down and let you up there so you can show them how to do it. You kind of talk them through it or want to say the right things. You want to be able to have them retain their confidence and at the same time be able to receive new ideas. Those are sometimes two mutually exclusive things. Some people take lecturing very well and others just want you to go away and let them do it the way they want to do it. It's difficult so you learn by doing, you're making all of these discoveries, sometimes you reach to pull out the carrot and you only get the top. But technique is not important, emotional telegraphing and truth is what is important and it requires no technique except emotional technique, but no actual, as to how many notes you can hear or how fast you can get there and how you fly it off those and the other notes, it doesn't really matter. That's what everybody wants to do when they come to the theatre - they want to connect.

Wilson: That's the most important thing, if you can connect with the public.

Notes:

(1) My wife and I had written a play called "Frank's Wild Years": Frank's Wild Years (the play) premiered on June 17, 1986 at Chicago's Briar Street Theatre. Further reading: Frank's Wild Years.

(2) We did "The Black Rider" and "Alice", both with the Thalia Theatre: The Black Rider: The Robert Wilson/ Tom Waits play premiered March 31, 1990 at the Thalia Theater, Hamburg/ Germany. Further reading: The Black Rider. Alice (the play) premiered on December 19, 1992 at the Thalia Theater, Hamburg/ Germany. Further reading: Alice.

(3) And now I notice chairs all over the world: refering to Wilson's obsession with chairs, and with Wilson having chairs in most of his theatre productions.

(4) And this gal Marie is a Coney Island baby: refering to "Coney Island Baby" being the theme song of the play (later released on Blood Money, 2002). It might be "Coney Island Baby" was a leftover from Mule Variations (1999), and Waits basically tried to fit the song into the play (as there is no refering to amusement park/ circus romance in the original play at all)

(5) My voice is going to be the voice of the monkey at this point:

Monkey puppet (w. Tom Waits' voice) as featured in the play.

Photography: Tom Waits Library