|

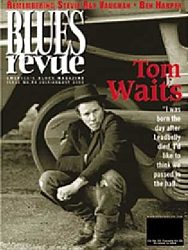

Title: Tradition With a Twist Source: Blues Revue magazine No. 59 (USA). July/August, 2000 by Bret Kofford. Transcription by "Pieter from Holland" as published on the Tom Waits Library. Thanks to Dorene LaLonde for donating magazine Date: July, 2000 Keywords: Mule Variations, Grammy awards, Age, influences, inspirations, songwriting, Johnsburg/ Illinois, Blues, John Hammond Magazine front cover: Photography by Mark Seliger |

Tradition With A Twist

He's somewhere between George Gershwin and a carnival barker, somewhere between Leadbelly and a guy selling vacuums from the trunk of his car. And Tom Waits -- playwright, well-known character actor, scorer of films, writer of stage musicals, Academy Award nominee (for the score to Francis Ford Coppola's 'One From the Heart'), devoted husband and dad -- is comfortable with that considerable breadth.

First and foremost, though, Tom Waits is a songwriter. He's had hit songs -- they've just been recorded by others, including Bruce Springsteen ('Jersey Girl') and Rod Stewart ('Downtown Train'). Recording a Waits song is a badge of honor for musicians in the know. Artists such as Beck, Los Lobos, Ani DiFranco, A.J. Croce and Eddie Vedder cite Waits as a major influence. He's won two Grammys, this year for best contemporary folk album for 'Mule Variations' and in 1992 for best alternative album for 'Bone Machine.' He also was nominated for a Grammy this year for best male rock vocal performance for the song 'Hold On.'

Yet Waits is, in essence, a bluesman. He cites Leadbelly and countless other blues artists as inspirations. Several songs on 'Mule Variations' are well within the realm of the blues ('Get Behind the Mule,' 'Chocolate Jesus,' 'Filipino Box Spring Hog' and 'Come On Up to the House'), and Charlie Musselwhite and John Hammond both appear on the album. Waits is in the process of producing an album for Hammond(1)

The son of schoolteachers from National City, Calif., has come a long way.

During his more than 25 years of recording, Waits, 50, has had long stints with Elektra and Island records. For 'Mule Variations,' he moved to Epitaph, previously known for punk-oriented recordings. Still, Waits' mix of clanging rave-ups, spoken-word landscapes, sing-along romps, roaring blues and tender ballads seems to somehow fit on the label.

The acclaim he has received over his groundbreaking and critically lauded career seems to have had little effect on Waits' ego. Waits was gracious, engaging and forthcoming with 'Blues Revue'. When the lengthy interview ended, Waits said he would call back "if I come up with anything else." He did so the next day, and beautifully played a portion of Gershwin's 'Prelude II' on his piano.

Blues Revue: When you started working on 'Mule Variations,' did you somehow anticipate you would be nominated for best contemporary album?

Tom Waits: Well, I don't go into it like that, thinkin' that. It's a nice thing, but it doesn't really drive me. Grammys are kind of like the Food and Drug Administration. People like to be USDA-approved, with the little sticker on it and everything. It's safer. It's kind of people formulating their tastes for what they like. They like the company of others. But it's a good thing.

BR: Do you think Epitaph is going to put a sticker on the album, that says, "contemporary folk album, of the year"?

TW: Oh sure, yeah. They'll probably do something like that.

BR: Would you even categorize yourself as a folk musician?

TW: Well, I don't know. That's OK, if you are going to call yourself something. I'm folks. I'm among folks. That's not a bad thing to be called if you've got to be in some kind of category. I have a kind of miscellaneous quality to myself, but I'll take folk. I started when I was a teenager playing folk clubs. That's all stuff I was listening to. I've gone a little bit far afield, but it still stays within that realm.

BR: Would you object to being called a blues singer?

TW: Well, I guess I would be flattered if someone said I was a blues singer. I'm not _just_ that, but I like that.

BR: Many of your songs could be classified as blues songs, right?

TW: Yeah, yeah.

(soon the discussion wanders into the qualities of a good tape recorder and other matters.)

TW: We've digressed, haven't we? I'd just as soon we digress the entire time. I never like walking in a straight line. The one thing about getting older, you get taller. We're not as close to the ground, and you miss a lot up here. My little boy(2) found a jewel that had fallen out of a cheap ring this morning. I never would have spotted it. But he's only 6 and he was right down in there. I miss that proximity to the ground sometimes.

BR: One of the good things about getting older is you start heading back to the ground again, you start shrinking.

TW: You start bending over. (Laughs) Yeah, right.

BR: Do you think your albums reflect where you're living at the moment? Your latest album, 'Mule Variations,' has a rural feel. Would you agree with that?

TW: Sure, yeah, it's definitely more outdoors, whatever you call it.

BR: And you're living in a rural area of Northern California?

TW: Yeah, it's a rural area, but . . . It's like people say [they] want to record in this studio because it's part of Georgia or Texas or Louisiana. Recording mostly happens inside your head. When you get to that point it doesn't really much matter where you are because the song really is the landscape. It has a lot to do with what you've been listening to and what you've been absorbing.

BR: So what kind of stuff do you listen to?

TW: Well, I dunno. There's only two kinds of music: There's good music and there's bad music, I guess, without running the risk of being too cliche`. Blind Mamie Forehand(3), 'Honey in the Rock'. That's the song. It's on the Victor label. There's a couple of mistakes on it, and it trails off. I like imperfections. I like things that have a little crack in them. That's how I get into a song. I remember hearing an old demo Roy Orbison did years ago, a song called 'Claudette.' He was just doing a demo at home and he got to a certain point in the song and he hit the wrong chord and said, "Oh shit." So he started over again. And I said, "Whoa, I can get in there." That's the thing with a lot of music. I think when it's expensive and heavily produced it puts off people when they hear it. They think, "Well, gee, my music is small and has bumps on it and has cracks in it."

BR: Do you put the bumps and cracks in on purpose or is that just the way it comes out?

TW: That's kind of just the way it comes out. And I've just stopped caring about it. It's gotten to the point where sometimes I do it or pursue it because it lacks ... what do they call it ... 'distressing.' But that one recording of 'Honey in the Rock,' when she stops and says, "Just taste and see." And someone sounds like they are banging on a telephone bell with a pen or something. They're just keeping time.

You know, we just buy music now. We don't make it any more. And that goes for just about everything. I think it's so important that people develop and subscribe to and have confidence in their own ability to make music, however rough it is. The rougher the better for me.

What have I been listening to? I've got all of those Lomax reissues, 'Southern Journeys', all that Library of Congress stuff that was recently released on CD(4), the Georgia Sea Island Singers(5) and prison songs and field hollars and a lot of Leadbelly. I was born the day after Leadbelly died. I'd like to think we passed in the hall. When I hear his voice, I feel I know him. Maybe I was a rock on a road he walked on or a dish in his cupboard, because when I heard him first I recognized him.

You see, I'm like everybody else in music. I don't have a formal background. I learned from listening to records, from talking to people, from hanging around record stores and hanging around musicians and saying, "Hey, how did you do that? Do that again. Let me see how you did that." And then I kind of incorporated it into what I was doing. I have a good friend, Francis Thumm(6), who used to play the chromelodeum with The Harry Partch Ensemble and he has been a music teacher for a lot of years, he has been a profound influence on me. He is a river to his people. And, Greg Cohen(7), my bass player for many years, is a complete renaissance man. He introduced me to everything from The Seeds to Arnold Schoenberg and everything in between. Mostly, I've depended on the kindness of strangers and people I know. Other musical teachers are Chuck E Weiss(8), who knows everything, and Kathleen Brennan [Waits' wife], who knows everything else.

BR: I interviewed A.J. Croce recently and he cited you as an influence, and you can hear your influence on a lot of other people, like Vic Chesnutt. How do you feel when people cite you as an influence?

TW: That's cool. Why not? Everybody's still really involved in the folk process of listening to each other. Even if you really try to do exactly what you think someone else did the night before, you can't, unless you're some kind of impersonator or impressionist. When you hear breakthroughs in music, it was their attempt to replicate something incorrectly, and that's what puts a hole in the door and lets the light in. You know, Chuck Berry was trying to play guitar the way Johnnie Johnson, his piano player, played keyboards, with the same kind of stride feeling. When I was a kid picking up a needle and trying to learn how someone did something over and over again ... it's kind of how it gets passed along, and I'm proud to be part of that whole tradition.

BR: Alan Rudolph has used your songs in at least a couple of movies(9), including your version of 'Somewhere.' Are you an admirer of Sondheim?

TW: Well, gee, I like those songs from 'West Side Story.' I'm a big fan of Leonard Bernstein. Those are all great songs. That's a great melody.

BR: Speaking of beautiful melodies, I love the little piano part on 'Take It With Me.'

TW: My wife and I collaborated on most of the songs ... and if it's really good it's probably her (laughs). Obviously she's more refined than I am. I'm more throw it against the wall ... Yeah, I like the little part, too. My wife's like a cross between Eudora Welty and Joan Jett. Kathleen is a rhododendron, an orchid and an oak. She's got the four B's: beauty, brightness, bravery and brains. She rescued me. I'd be playing in a steakhouse right now if it weren't for her. I wouldn't even be _playing_ a steakhouse. I'd be _cooking_ in a steakhouse.

BR: What was going wrong in your life at that time?

TW: What wasn't going wrong?

BR: What year did you meet?

TW: 1979. We met on New Year's Eve.

BR: But you did some good stuff before '79.

TW: But I was falling apart. I was all over the road.

BR: OK, what do you write first, the words or the music?

TW: That's one of the oldest questions in the book.

BR: I didn't want to ask it.

TW: But you did. And the thing is, words are music. If you have words, you have sound, and the sounds have a shape to them. And in that sense, in the broader sense, music is organized noise. Monk said there are no wrong notes. It all has to do with how they are resolved. That's how jump-rope songs were. They're a rhythmic phrase. As soon as you have that you have music. So you don't have to wait for the words if you have music. And sometimes you don't have to wait for the music if you have the words. I don't know who said this, but they said all things aspire to the condition of music at its best. Everyone is looking for that in many things.

BR: Charlie Musselwhite plays a lot on the new album. Have you heard his Latin thing ['Continental Drifter']?(10)

TW: The Cuban thing? Yeah, I like it. It seems like it goes together. He was probably worried about translation, disparate musical styles, but there's always an overlap. At some point, Chinese music starts sounding Irish. Who knows why?

BR: So you brought Charlie Musselwhite in because you wanted to use the best harp player you could find?

TW: Yeah, (laughs) he's great. He brings about 300 harmonicas, microphones. And he's up for anything. Some stuff adapt to that cross harp, but the songs that we tried it on did. On 'Chocolate Jesus' just before the song starts you can hear him talking into the mic. He says, "I love it." That's my favorite part of the song.

BR: When you're playing with all these famous people and you hear all these things about people being your admirers, do you ever think, "I'm just another guy who plays music. I don't need all that"?

TW: Well, it's important to remind yourself of that. It's a balancing act. I really do want to stay humble.

BR: One more thing to shatter your humility. I love your song 'Johnsburg, Illinois.' It's such a beautiful song. Is there really a Johnsburg, Illinois?

TW: Yeah, my wife grew up there. It's by McHenry, near the Chain of Lakes. It's the last place you can get margarine before you cross over into Wisconsin.

BR: You can't buy margarine in Wisconsin?

TW: It's the Dairy State. Are you kidding me? If you're even caught with margarine on you ... they search you at the markets.

BR: And at the border station they check you.

TW: Yeah, there's a margarine check.

BR: Tell me about blues artists you like, you grew up listening to.

TW: Well, I used to play on the bill with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. That was a big thrill for me. The song I love the most is that Skip James tune "Look at the People." It reminds me of the Son House tune "John the Revelator," which I'm a big fan of [I listen] to old field hollers and work songs and jump-rope songs and chain gang tunes and call and response. Let's see. What else? Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Of course, Ray Charles, Speckled Red, Koko Taylor, Big Joe Turner, Peetie Wheatstraw, Professor Longhair, Canned Heat.

BR: Is there anyone out there who catches your ear now?

TW: ... T-Model Ford. The stuff on Fat Possum I like a lot.

BR. You worked with David Hidalgo. Do you like his stuff?

TW: Oh, man, yeah, I love those guys. I love Los Lobos. Those guys out of Denver, 16 Horsepower. What about Sparklehorse? He's great. Lou Ann Barton, she's got a great voice ... [Captain] Beefheart, of course. Elvis Costello. He's a renaissance man, he's multidimensional. His song "Baby Plays Around" I thought would be a good song for Little Jimmy Scott, who is someone else I really admire a lot. Howlin' Wolf, of course. The 3M Corporation - Monk, Miles and Mingus. Roland Kirk is up there really high. Sun Ra, Cryin' Sam Collins, James Harman, Tina Turner, Aretha, Daniel Johnston. And I like anybody with "little" in their name. Little Jimmy Scott and, uh ...

BR: Little Charlie & The Nightcats ...

TW: Little Charlie & The Nightcats ... all the Littles, and I like all the Bigs ...

BR: Big Mama Thornton ...

TW: Big Mama Thornton, Big Joe Turner Big Bill Broonzy, Little Anthony & The Imperials, Little Richard ... Zappa, Nick Cave and, of course, The Rolling Stones, can't leave them out. Bill Hicks, Johnny Cash, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Guy Clark, Randy Newman. And Harry Belafonte. My dad had all his records. I just put him on the other night and said, "Man, Harry, you're killin' me." The thing about recording ... it is a pretty miraculous phenomenon when you think about it. You put something that happens in three minutes time and someone can come along a hundred years later and hear what you did in those three minutes. It's rather mystifying. And you get a chance to shake hands with the future and be part of the past.

BR: Do you consider yourself a good piano player?

TW: I play fake piano. I'm a composer, basically. When I sit down at the piano I don't sit down to play something or learn something. I sit down to discover.

BR: So when you hear a really good piano player, like Gene Taylor, you say, "I could never do that."

TW: Jeez, man, get out of here. But that's not my thing. I took a different road. I used to dream about the Brill Building and to write songs in that manner ... I love the whole cabaret tradition. I liked listening to Sinatra when I was starting out. My friends thought I was crazy. They were listening to Blue Cheer. And Leadbelly. It's like when I discovered Leadbelly I discovered mariachi music, Irish music, gypsy music. You make a connection with it and you don't know why.

BR: How's it working out with Epitaph?

TW: Good place to be, compassionate and young.

BR: They haven't had anyone like you before.

TW: No ... they brought me in for adult supervision. Yard duty. They're honest. [Epitaph founder] Brett Guerwitz is an innovator and a visionary and an iconoclast. He's very fair in all ways. He's not a gouger. They see themselves as more a service industry. You make music and they put it out. They're not part of the long tradition of the rape and pillage of artists, and the servitude. You get a lot of respect there.

BR: I read another interview with you where you said the term "you gotta get behind the mule and plow" from Mule Variations is something your dad used to say to you, an old saying about getting to work.

TW: No, that's what Robert Johnson's father said about Robert. He said he wouldn't get up in the morning and get behind the mule and plow. Robert wanted to have his own life and get out of the whole system there, so he flew the coop.

BR: What does Kathleen contribute to the writing process?

TW: We collaborate. Who knows how it really works, if it works? You know, you wash, I'll dry. She stays out of the limelight. That's what she prefers. I'm out there, I'm more song and dance, and she's more behind the scenes. She prefers it there.

BR: In retrospect it looks like she's added depth and textures to your albums that weren't there before.

TW: Well, you're married. You know how it is. She's the brains behind Pa (laughs).

BR: Do you ever listen to your old things and think "That's not very good'"?

TW: Yeah, I do. I can't listen to the old stuff. I've got big ears and I dressed funny. And I have a monochromatic vocal style. I have a hard time listening to my old records, the stuff before my wife.

BR: Where's the threshold where you can say, "Well, I kinda like that one"?

TW: Oh, I dunno Swordfishtrombones, and forward from there. That's a line of demarcation for me. And that's right around the time I got married [1983], and my wife worked on that record with me. She's the one who said, "You can produce your own records, you don't need to go in with a staff and people telling you what to do." That started what became more of a mom-and-pop outfit. Till then I felt like I was trying too hard. You learn what not to play, what not to say, which is critical at all times. And in most cases that which is implied speaks volumes, in music particularly.

(The conversation returns to the blues,)

TW: Well I guess blues is in everything now. It's an ingredient that is so seminal and such a Rosetta Stone or wellspring, but now it's like that which was once a river becomes a road. The place where giant rivers cross, there's a great deal of electromagnetism. I love listening to old gospel stuff. You know that disc that came out that John Fahey's on, Charlie Patton on the cover [American Primitive, Vol. I]? It's just a terrific collection, and the artists on it are just remarkable ... prewar gospel, 1926-36. You can hear that Blind Mamie song on there.

BR: If 50 years from now you're remembered for writing 10 great songs, would that be enough for you?

TW: Well, I've still got some time (laughs). I think what it does come down to, because we're just plain human or we're so product-oriented, we like our products, and we want access to our goods and services, and we want to know what's best. That's what I hate about those "best of" records. You have to see most of this work in context.

I dunno I think you're being a little generous.

Musician's Corner

Tom Waits and John Hammond, longtime and occasional musical associates, have been working together on a new Hammond album recent months.

While the pairing of the musically daring Waits and traditional blues hero Hammond seem a strange one, Waits said the sessions "have been great. I used to open up for him, when I first started playing clubs. Don't let him open the show for you, because everybody will leave after he gets done. He's so good. He sounds like a big train coming. one guy. He gets those chops down so strong."

The two kept in touch over the years, and Hammond played harmonica and guitar on Waits' Mule Variations. They then decided that Waits should produce Hammond's next album

"John is an exceptional in and I admire him. He asked me to produce the record and I said to myself, 'Jesus, how could I say no?' Except I don't know what that means, to produce a record. 'You mean stand around and drink coffee while you play?' "

Waits had only produced his own records, "so I was a little nervous about it and I almost backed out because it was too intimidating. But I picked the studio and the musicians.

"He's doing some of my songs, and he's doing some trad stuff. He's done so many different things it's hard to find a place that he has not explored." Among the Waits songs Hammond has recorded are "Murder in the Red Barn," "Sixteen Shells From a Thirty-Ought Six," "Gun Street Girl" .. "a lot of ammo tunes," said Waits.

Both Hammond and Waits were overjoyed with the supporting cast during early sessions in Northern California. "We're working with Larry Taylor (bass) and Steven Hodges (drums) and Augie Meyers (keyboards). It's going great," Waits said.

Hammond said he is enjoying doing a range of both old and new Waits tunes. "I've known Tom a long time and I've always admired his thing. I've been on some gigs with him and watched him play a lot of blues stuff. He knows that kind of idiom."

To work with musicians such as Hodges, Taylor (formerly of Canned Heat) and Meyers (The Sir Douglas Quintet, The Texas Tornados) "is really dynamic. I'm very impressed. I'm seeing a whole other world," Hammond said. "I'm seeing myself as being able to do this new material It's just a wonderful adventure again."

Notes:

(1) Producing an album for Hammond: "Wicked Grin", John Hammond (Emd/Virgin.) Released: March 13, 2001.

(2) My little boy: That would be Sullivan (born 1993). Other children: Kellesimone (1983) and Casey-Xavier (1985).

(3) Blind Mamie Forehand: "If women didn't often sing the blues in the 1920s, they did sing gospel. Blind Mamie Forehand sang many a spiritual on the streets of Memphis, and her "Honey in the Rock" (recorded in 1927) is a delicate example of the genre.". released on: "Storefront & Streetcorner Gospel (1927-1929)" Document Records. Various Artists. Recorded at: Memphis, TN. Original Release Date: 06/02/1994.

(4) Lomax reissues, 'Southern Journeys', all that Library of Congress stuff that was recently released on CD: "Alan Lomax was the son of famed field archivist John Lomax, who did a series of field recordings for the Library of Congress in in the years before WWII. Alan picked up where his father left off and in 1959 embarked on a landmark tour of the rural South to do further recordings of American Folk Music." A set of 6 CD's was released in 1997 by Rounder Records under the title "The Alan Lomax Collection." The collection will be released by Rounder in segments, the first group of 6 CD's was titled "Southern Journey".

(5) Georgia Sea Island Singers: "African-American heritage, a mixture of English and African dialect, along with work and escape songs, sea chanteys, call-and-response and overlap tunes. Discovered by Alan Lomax, the founder of the group was Miss Bessie Jones who had been encouraged by author Lydia Parrish to share the songs of her heritage which emanated from the southern barrier islands. Frankie and Doug Quimby joined her in 1969 and became the second generation of the Georgia Sea Island Singers. Further reading: Georgia Sea Island Singers.

(6) Francis Thumm: long time friend, musician, teacher. Further reading: Who's Who?.

- Chromelodeon:

- The Chromelodeon was never used on any Tom Waits record. Harry Partch built his Chromelodeon in at the University of Wisconsin. Reeds are inserted for a 43-tone-to-the-octave scale. Thus, an acoustic octave covers that many keys and reeds, successively, and measures some three and a half keyboard octaves. The scale is in just intonation, and each tone is a frequency ratio to a fundamental, shown on the keyboard by colors. With the thirteen sub-bass reeds, and the stops for higher and lower tones in the second cell row, the total range of the instrument is from the lowest piano C to the third C# above middle C, slightly more than five acoustic octaves.

- TW (1983): "Lately I've found an appreciation of Harry Partch who built and designed all his own instruments and died several years ago in San Diego. His ensemble continues under the name of The Harry Partch Ensemble, a friend of mine, Francis Thumm, plays the chromelodeon." (Source: "Skid Romeo" The Face magazine #41, by Robert Elms. Date: Travelers Cafe/ Los Angeles. September, 1983)

- TW (1983): "That's (Underground) Victor Feldman on bass marimba, Larry Taylor on acoustic bass, Randy Aldcroft on baritone horn, Stephen Hodges on drums and Fred Tackett on electric guitar. I had some assistance from a gentleman by the name of Francis Thumm, who worked on the arrangements of some of these songs with me. Who plays gramolodium with the Harry Partch Ensemble headed up by Daniel Mitchell. So he worked closely on most of these songs" (Source: "A Conversation with Tom Waits (Swordfishtrombones)" Island Records music industry white label 12" promo. Date: September, 1983)

(7) Greg Cohen: longtime friend, bass player, brother in law. Further reading: Who's Who?

(8) Chuck E Weiss: long time friend (1970's), musician. Further reading: Rickie and Chuck

(9) Alan Rudolph has used your songs in at least a couple of movies: Only movie known is: "Afterglow" (1997). On soundtrack: "Somewhere" by Tom Waits.

(10) Have you heard his Latin thing ['Continental Drifter']?: Charlie Musselwhite "Continental Drifter". Released in 1999 from Virgin Records. "Continental Drifter is comprised of music which, according to Charlie, "reflects who I am today as a musician and a human being." The tracks on the album are divided into three sections. The first section, "The Band Session" features Charlie and his touring band, whom he says, "can play whatever I have a mind to play." Session two, "The Solo Session," incorporated the Delta sounds Charlie grew up with. For the third section, "The Cuban Sessions," Charlie recorded four tracks with his Cuban friend and colleague, Eliades Ochoa and his group Cuarteto Patria. Many of the album's tracks are entwined with Cuban and Brazilian sounds that have been a major influence on Charlie's music over the years. "My experience with the Cuban and Brazilian musicians whom I have met and played with is that we are all excited by the possibilities of blending the musical cultures, sometimes just for the joy of playing together, sometimes in the hope of fostering understanding and tolerance between our cultures." (Source: Rosebud Agency, 1999)