|

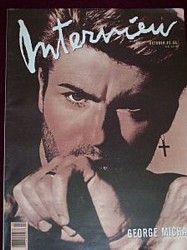

Title: Tom's Wild Years Source: Interview Magazine (USA), by Francis Thumm. October, 1988. Thanks to Larry DaSilveira for donating article Date: Livingston. 1988 Key words: Francis Thumm, Cold Feet, Musical influences, Childhood, Sam Jones, Nessum Dorma, Bette Midler, Ox-Bow Incident, Big Time, Kathleen, Studio recording, The Black Rider, Jack Nicholson, Bob Dylan, Harry Partch Magazine front cover: Interview Magazine (USA). October, 1988 |

Tom's Wild Years

Between takes in Montana, character musician Tom Waits catches up with longtime friend Francis Thumm.

Since his first appearance twenty years ago on the floors of little-known late-night clubs in the backstreets of L.A. Tom Waits has been creating a universe all his own, an American dystopia sung in ballads, blues, laments and elegies. His vision and character are as American as Bruce Springsteen's. But where Springsteen sings of the American dream Waits is stuck somewhere in the lost latitudes of an American nightmare.

His world is one of "sad-luck-dames", "crumbling beauties" and drunken sailors on shore leave. Doughnuts "have names that sound like prostitutes". Waitresses have "Maxwell House eyes and scrambled yellow hair": the dawn "cracks out a carpet of diamonds across this cash crop car lot, filled with twilight Coupe de Villes."

Waits was born in 1950 in the back of a cab in Pomona California and grew up in Whittier, San Diego and Los Angeles. He lived - like a character in one of his songs - inside a car, worked as a doorman at a local nightclub(1) and started singing in bars in his teens. At 23 he released his first album "Closing Time", a compilation of his own ballads and folk blues. Years later after his fabled stint at the Tropicana Motel(2) on Santa Monica Boulevard in L.A. after the drugs, the time with Rickie Lee Jones, the nights spent swimming in the alcoholic haze of seedy barrooms and back-alley dives, the days spent hitchhiking to club dates and gigs, he developed the cigarette-stained and Scotch scratched voice that has become his trademark and his success.

The line between Tom Waits the person and Tom Waits the persona - the raconteur, the troubadour, the Gila monster of Lounge Lizards - has always been thin. It used to be hard to separate the man behind the microphone from the characters in his songs, for Waits confused the facts from his own life with those of his characters, routinely remythologizing himself in his own self referential universe. In the last few years however Waits has stepped out of the shadows cast by his own characters. Since working in film he feels more comfortable with creating characters that, according to Waits, "have their own anatomy, their own itenerary, their own outfits."

At 38 Tom Waits is entering a new phase of productivity and, as it happens has settled down. In the past year alone he has appeared in Hector Babenco's Ironweed and Robert Frank's Candy Mountain, toured the United States with his theatrical Franks Wild Yearsshow, made the concert film Big Time and acted in the upcoming feature Cold Feet directed by Robert Dornhelm. Early next year he will work with the theatre artist Robert Wilson on a new musical drama in Munich(3).

With his flurry of high-profile film appearances, Waits has moved in from the margins and has come closer to the mainstream than ever before. He's done this without compromise: the commercial world has simply caught up with him, and his soup-kitchen style has been exonerated and even romanticized. He has matured musically as well, moving on to new lyrical landscapes, leaving behind the dingy urban barroom for the more eclectic terrain of small-town Americana. In his last few albums he has mixed nursery rhymes, Kurt Weill, country music, pump organs, and Southeast Asian instruments into his rich "junkyard" orchestration. Tom's wild years in short, seem to have come to an end, and the most productive ones are just beginning.

Part of the change has to do with Kathleen Brennan, a playwright and short story writer whom he married eight years ago in Watts at the Always and Forever Wedding Chappel on Manchester Boulevard open twenty hours. Brennan and Waits have written songs and theatrical pieces together and have co-produced two children as well, daughter Kellesimone and son Casey.

Francis Thumm first met Tom Waits in 1969 and has collaborated with him, as a performer and co-arranger on several albums. Of his friendship with Waits Thumm writes. "It is divided between a mutual love of music and a compulsion to engage in elaborate and colorful histories of events and personalities that never existed. We would attend a concert by Arthur Rubinstein and follow it with an improvised conversation between two late-arriving plainclothes security guards who were blaming their incompetence on blocked chakra while stationed at Club Nahqui - a legendary watering hole with drawing rooms named The Hall of Yells, Rat Landing, and The Cherry Room."

Waits was filming Cold Feet when Thumm tracked him down in the backwoods of Montana, in a small place called Livingston. The interview began, in typical Waitsian fashion far beyond midnight outside an isolated ranch in the countryside. Waits grabbed a matchbox and let off a round of firecrackers. Thumm poured himself a Ballantine's Scotch and lit up a Partagas cigar: Waits did the same, and the conversation lasted long into the early Montana morning.

FRANCIS THUMM: You were in the swimming hole today and you said. "This is the best summer I've had in a long, long time." Being out in Montana on this location. Didn't you often go to Mexico on a ranch when you were a child?

TOM WAITS: When I was a kid, yeah. But my wife and I have been grid locked in L.A. for so long, and I would like to exchange the dynamic so that going into town would be what going into the country is now. Now we're living out here, where it's beautiful because of the mountains, the prairie, and the wide open spaces: it takes the top of your head off. There are so many rocks around here. God's marbles. I like what my daughter says. "All the sparkle rocks are good people who died. All the little ones you're not interested in are bad people."

FT: You're out here working on a film called Cold Feet. What kind of a story is it?

TW: I don't know what you'd call it. I guess it's a road picture. I play Kenny, a highly malfocused individual who I think is from Miami. He has a mother fixation, gold chains, blond hair, and a pinkie ring. He's made twenty-three consecutive hits without a famous last word from any of them. I like him because he's a hothead. I play the third side of a triangle including a shrew of a woman named Maureen and a dishonest cowboy named Monty. I'm working with good actors: Rip Thorn, Sally Kirkland, Keith Carradine, and Bill Pullman. Robert Dornhelm the director is great.

FT: What are some of your earliest memories of music and sound, and which people left a musical impression on you?

TW: Well Mario Lanza used to play golf with my dad, and my mom used to get her hair done with Yma Sumac. I went to a baseball game with Little Walter, and he told me I should get into show business as soon as possible. But I think the clearest memory I have is from when I was about 8 years old: I had a friend who lived in a trailer van(4) by a railroad track, and his mom was enormous. I think she had got in the trailer, put on weight, and couldn't get out. There was a lamp, a TV, and a beverage, and she always seemed to be in the same spot. Anyway, when he played, it was the first time I ever heard anybody play in a minor key, and I really recognized it as minor and was attracted to it. I still am. He taught me three chords-an A-minor blues progression-and I completely flipped. When I went to school the next day, sharing day, I got up in front of the class and played the guitar. Everybody else was sharing marbles and rocks. That was a big moment for me.

Then there was Uncle Robert. He had a tremendous rose garden, and he was a blind organist in a Methodist church in La Verne, California. In fact, after they tore the church down he took the pipe organ into his living room. I remember listening to him play the organ. And as his eyesight began to fail his performance seemed to drive into more interesting places.

Other sounds I remember: a train that went by my backyard in Pomona and my mother's steam iron when it was boiling.

FT: You played trumpet in junior high, didn't you?

TW: First trumpet. I had a Cleveland Greyhound silver trumpet(5), which was given to me by my uncle, and I played reveille and laps for the raising and lowering of the flag each day, which was one of my early performances, I guess.

FT: Why did you abandon the trumpet in favor of the guitar?

TW: I always liked the shape of the guitar and, of course, the hole in the middle. I think that's what most boys are attracted to in a guitar- the curves.

I hitchhiked to Arizona with Sam Jones(6) while I was still a high school student. And on New Year's Eve, when it was about 10 degrees out, we got pulled into a Pentecostal church by a woman named Mrs. Anderson. We heard a full service, with talking in tongues. And there was a little band in there - guitar, drums, and bass along with the choir.

FT: Was that the first time you heard music like that?

TW: Yes it was the first time I ever heard church music, with sexual innuendoes.

FT: Well. You had heard Motown at that time, so you were going in backward right?

TW: Yeah I mean. I had heard the church in the street, but that's the first time I heard the street in the church. There have been other exciting musical things: the Japanese Tango Orchestra right off Times Square. The first time I heard Puccini's Nessum Dorma(7), Gershwin's Second Prelude, and mariachi music.

FT: Was that when you used to go to Mexico with your dad?

TW: The music down there was never an event, it was always a condiment, and I liked that. It's still like that where I live in L.A. I go down to the liquor store, and there's a guy standing on the street corner with an accordion and a guy with an upright bass.

FT: Here. if you took an accordion and an upright bass into Denny's they'd arrest you.

TW: Well, here it's not the practical, it's the - what's the word I'm looking for - the "turbulence" and "urban". Here it's commerce, not culture.

When I was a kid I hung out with a gang of Mexican kids in a town called San Vicente. And in the summer, we used to go out into the desert and bury ourselves up to our necks in sand and wait for the vultures. The vultures weigh about seven pounds 'cause they don't eat right. They're all feathers. You wait for the buzzards to start circling over you, and it takes them about a half-hour to hit the ground. You stay as still as a corpse under the sand with just your head showing, and you wait for the vulture to land and walk over to you, the first thing they do is try to peek your eyes out. And when they make that jab, you reach out from under the sand, grab them around the neck, and snap their head off..

I'll tell you, the best thing I ever saw was a kid who had a tattoo gun made out of a cassette motor and a guitar string. The whole thing was wrapped in torn pieces of T-shirt, and it fit in your hands just like a bird. It was one of the most thrilling things I'd ever seen, that kind of primitive innovation. I mean, that's how words develop, through mutant usage of them. People give new meaning, stronger meaning, or they cut the meaning of the word by overusing if, or they use it for something else.I just love that stuff.

FT: When did you first get the impulse to write words and music of your own?

TW: Real young I heard Marty Robbins "El Paso" and the fact that it was a love story and that crime was involved really attracted me. [laughs] But it's not like once you've developed the ability to write songs, it's something that will never leave you. You're constantly worried that it may not come when you want it to. It still comes down to this: you may like music, but you want to make sure music likes you as well. You sometimes frighten it away. You have to sit in a big chair and be real quiet and catch the big ones. Then try to get something you consider to be innovative, within your own experience. It takes a long time. I'm just starting to feel that I can take some chances now; I wrote in a very traditional way for a long time. Sat at a piano with a cigarette and a drink and did it in kind of a Brill Building style. I was always fascinated with how these guys could go into a room, close the door and come out with ten songs. You may think you're doing good, but then you hear Thelonious Monk, Jimmy Reed, Keith Richards, or Mississippi John Hurt, and you realize that these guys are all blessed in some way, and when are you going to wake up with the golden fleece?

FT: When did you first see yourself as a songwriter?

TW: Actually, even after I had made records. I didn't feel completely confident in the craft until maybe Small Change. When I first put a story to music. I fell I was learning and getting the confidence to keep doing it. "Tom Traubert's Blues" "Small Change" and "I Wish I Was in New Orleans" gave me some confidence.

FT: Some of your earliest tour bookings were legendary. For instance, you opened for Buffalo Bob and the Howdy Doody Revue(8) in Georgia.

TW: And Bob called me Tommy.

FT: You didn't like that, did you?

TW: I couldn't stand it and I told him. "Bob. please don't make me hurt you. I have a breaking point."

FT: That's a weird line to use with a guy who holds a puppet with a plastic head.

TW: And it was very strange, having seen him when I was a child....

FT: And there you were yelling at him.

TW: He had had a big place in my life as a child. Later, when he was having a come-back. I was his opening act. We did matinees at 10 a.m. for screaming children and women in curlers, and there was candy in the piano. Show business was starting to look like a nightmare.

FT: Bette Midler attended some of your earliest New York concerts(9). What was that like?

TW: Well, she came in with all the feathers and ermine and red hair on fire, trailing ten or twelve people behind her. She was moving turbulence. She was in the audience, and I think we became friends right away.

FT: What did she say about your performance?

TW: She said. "You need some feathers, girls, hula skirls, and beaded curtains, and then you might have something." I wrote some songs for her. like "I Never Talk to Strangers" and "Rainbow Sleeves."(10) As soon as I met her, I felt like I had already known her she can do an hour on your hair. We can talk about anything. I love her musical impulses; she has a great sense of history in terms of her involvement in show business. She wanted to open a lounge act together, featuring us as Edie and Edie Wednesday. We've been friends for a long time, you know, since '74.

FT: When you were on tour in those days you created a mythology of street people but didn't the dividing line between the imaginary world and the real world begin to blur?

TW: There's a tunnel that goes back and forth.

FT: Like the time you were in the Chelsea Hotel watching TV?

TW: Well the story now has come to be known as the Ox-Bow Incident, because that's the film I was watching, in my underwear at the Chelsea, in the middle of February; it was 40 below.

FT: I'd like to ask why you were in your underwear when the weather was 40 below?

TW: Well. I'm in my room, I'm well protected. I've got steam heat, and I'm really comfortable. I'm looking out the window, and the snow's coming down. It's getting to the good part in the movie. I got a little Myers' rum. It's about 2 in the morning, and all of a sudden the key goes in the lock and the door opens. My first thought is. OK, the night clerk, uh room check, cleanup maid. I look over and coming into the doorway is a guy in a down jacket with his hand inside his coat, looking real nervous, looking scared, and he has a girlfriend with him. All of a sudden there are three of us in the room. It's a small room. The door closes behind him, and the first thing he does is reach inside his jacket. He tells me. "It's O.K. buddy, you can stay" I'm about to reach for the phone to call down, because I know there's something wrong here and I know that this is my room. But he doesn't want me to use the phone, so I don't. His girlfriend goes into the bathroom and starts crying, and he comes over to me very calmly and says. "It's O.K. man, you can sleep here; we'll sleep over there" and he starts watching the TV with me.

Well. I'm trying to get my pants on and be real comfortable, and I say. "Listen, you know it's a hotel and there's lots of room, and I think that... you guys are having a problem here. I know how it is. You want your own privacy, and I want my privacy; let's get you a room. Let's call down and get you a room." I reached in my pocket and pulled out a $100 bill, and I said. "Here. I want you to have this. Get yourself a room." and he couldn't believe this, but I realized that maybe that $100 was the best $100 I would ever spend. Anyway, he went downstairs, got himself a room, and I, of course, figured I'd never see the $100 again. I thought. It's worth it because he's gone. He came back fifteen minutes later and gave me change. And he was blessing himself and blessing me and talking about Mother and Mother Mary, and the baby Jesus, and St. Vincent de Millay, and the Pope, and he was crossing himself and bowing and saying things in Spanish. And I went back to The Ox-Bow Incident. It was just wrapping up; the hanging had already taken place.

What had happened was, the girl had stayed in my room the night before. She picked up another John on the street and had figured. I'm gonna hang onto the key - you know. use the room tomorrow night for nothing. By then of course, it was my room. This happens a lot at the Chelsea, and they never change the locks or the keys.

FT: Your new concert film Big Time, directed by Chris Blum is being released in October. You play a character with a pencil thin mustache who sweats a great deal. He works at the theatre, goes home to sleep and dreams he has the starring musical role. And you're weaving his activities through the concert.

TW: Well. it's never done as a linear piece of fiction. It was just a way to try and create some kind of other dimension and stability. Concert film is a bit of an orphan because you're filming something that happened live. There are inherent problems with it. Even when it's great you think. It's great, but shouldn't we have been there? Is that all you want me to feel-that I missed it, that it happened and I wasn't there?

FT: There's some unusual direction from Chris Blum - the colors, mood, pacing and camera angles seem out of Fellini at times. And the atmosphere is more like that of a mad carnival than a concert film.

TW: I told Chris. "Film it as if you were at a Mondo Cane voodoo ceremony - if you get caught, you get killed." because I didn't want cameras on the stage. This excited him. We did it in only two nights of concerts - six cameras the first and two the next. If we had had more money, we could have done the scene with the Chinese ladies, the midgets, and the Portuguese horses.

FT: Big Time is your first ever concert film. You've seen the final version. How would you encapsulate it?

TW: It's Swabbie night at the Copa shot through the lens of an African safari rifle. Basically it's an action film.

FT: I've always felt that Kathleen, your wife, has had a great influence on you and your career.

TW: We've been married for eight years and we're partners. Kalhleen's a great collaborator She's quick - she can catch a bullet in her teeth. She has a pet snake, reads The Wall Street Journal, has a '64 Caddy, and loves periodicals. She's from Johnsburgh. Illinois; that's the last place you can get margarine before you cross the Wisconsin border. No one makes me laugh like Kathleen. She got me listening to Frankie Laine, Rachmaninoff, and John McCormick. We write together, and she wants to do a two-character drama about a singer and his giant bald-headed limo driver who has a US Road Atlas tattooed on his head, wherever he itches his head that's where they play next. She's great in emergencies and she's brutally honest. Her own writing - her stories - is strange, bizarre and wonderful. Tragic and very Irish. She's real black Irish. Kathleen has a great sense of story and of the architecture of a story. I have a tendency to go back over familiar ground, and she's much more of a pioneer.

FT: So she'll remind you if you're repeating yourself?

TW: Always. When we write songs together. I fight her all the time because she's usually right and I feel compelled to, Kathleen has great musical instincts. She's a bit pedestrian at the piano, which is good because playing the piano is like being in a truck - you may be able to go some places in it, but you don't have this weightless ability to do any kind of flying or dipping or plunging. She doesn't let the piano stay in the room. She goes out the window with it, and that's what I love: it's very beautiful.

Lately I like to get inside the piano with timpani mallets and lie across the strings and bang on them, because after a while the hand has a memory, and when it goes somewhere, it knows what to do - how to wrap around something, or what to do on the keyboard. And you have to kind of give it a stroke. You have to put an electric fence around it so it doesn't go where it wants to go, because the hand has an intelligence all of its own, almost separate from you. I'm Just learning how to deal with it. Kathleen has been a big part of that.

FT: In what way?

TW: Because she's a woman; she has four-dimensional ability. You get very linear sometimes in music; you know the logical steps.

FT: And you rely on old formulas.

TW: Yeah. And you know what makes you safe and you don't want to be unsafe. Kathleen has helped me to feel safe in my uncertainty. And that's where the wonder and the discovery are. After a while you realize that music - the writing and enjoying of it - is not off the coast of anything. It's not sovereign, it's well woven, a fabric of everything else: sunglasses. a great martini, Turkish figs, grand pianos. It's all part of the same thing. And you realize that a Cadillac and the race track, Chinese food, and Irish whisky all have musical qualities.

FT: I heard that Duke Ellington sometimes used to give his musicians a description of something or somebody, rather than technical musical directions, to get them to play the way he wanted.

TW: Yeah, that happened in Chicago when we recorded the Frank's Wild Years album. On "I'll Take New York" they approached the whole recording like a Strasberg kind of thing [laughs] I said. "let's go with Jerry Lewis on the deck of the Titanic, going down, trying to sing 'Swanee'" I sang the song right into a Harmon trumpet mute and just explained that I wanted the whole thing to gradually melt in the end.

FT: You did that with quite a lot of songs on Frank's Wild Years. I think you gave some of those songs a nervous breakdown. They were fairly conventional, written for the stage, and when you went to make the album, they got transformed.

TW: It's a matter of pulling the play into the song; once I separated the music from the story. I felt compelled to put some optical illusions in the songs. Some were more susceptible than others, but I was trying to make them more visual.

I worked with great people. It has to do with the chemistry of the people that you work with. Mark Ribot was a big part of the thing 'cause he has that kind of barbed-wire industrial guitar, Greg Cohen is solid; he plays both upright and electric bass. Ralph Carney plays three saxophones simultaneously. Bill Schimmel doesn't play the accordion, he is an accordion. They enjoy challenges. Michael Blair will play everything. He plays every instrument in the room and then goes looking for things to play that aren't instruments. They all are like that, and it's like a dismantling process-nothing carries its own physical properties by itself.

You can talk to them like actors, and they'll go with the drug, and that's what I like. You have to really know your instrument; you have to understand the power of suggestion to be able to do that. I can literally talk colors. I can say, "We want kind of an almond aperitif here" or "industrial hygiene with kind of a refrigeration process on this" and they say, "Yeah. I'm there. I'll go there." And that's exciting. Like Mark Ribot - we were playing after hours in a club in Copenhagen(11) I think it was, and he knocked over a bottle of some foreign liquor; it was spilling all over the floor and he's splashing around in the liquor, jumping up and down playing the guitar, yelling. "Play like a pygmy, play like a pygmy." And everybody knew exactly what he meant. When you find who you communicate with on that level, it's very exciting, because they'll go anywhere with you.

And they were all the best part about the movie Big Time, including Willie "The Squeeze" Schwarz, even though they weren't on camera that much. Sorry, boys.

FT: You recently recorded the Seven Dwarfs' work song "Heigh-Ho."(12) for a Disney album produced by Hal Willner, and it sounds like a rap meltdown-like you're being squeezed through some serious machinery. It's not anything like the Dwarfs of my childhood. Why did you do that?

TW: You listen to those songs now as an adult and you can't really escape back into what they represented for you when you were that age. Work takes on new meaning when you do it for a living We used tools-machinery from an airplane hangar and some jail doors and pile drivers. I played it for my daughter, and she said, "That must be where they push the witch off the cliff into the boiling water."

FT: You're scheduled to work with Robert Wilson beginning next February in Munich.

TW: What I like about Robert Wilson is, he'll go through his calendar when you're talking about doing something, and he'll say very seriously, "Well. I have a little time in 1998." And he's not joking. And in 1998 you'll get a call.

FT: What project is this?

TW: I don't even know. At the start it was called a "cowboy opera"(13) and I don't know what that meant. He's very oblique; he'll tell you, "There are three principal characters in this, Tom, and all the other people will be carrying spears. Now I want you to go away and write something." It challenges you because it deals with big symbols. I want to work on it with Greg Cohen; he just finished arranging and producing an album - all the Hanns Eisler music- for Dagmar Krause for Island Records. He uses oboe, bass clarinet, low brass, low reeds, and it's real wooden, he uses almost no percussion, but all his percussion is handled by the attack of the low reeds: [sings] "Cha. chung. chung. chung. chung." I love that. I know Wilson is right into the Eisler stuff and loves the German composers, but I don't know anything about the rest of it.

FT: Well, you saw Einstein on the Beach.

TW: It was real long, but it's the closest thing to film I've ever seen in the theater because of what he does with the light. And everything is timed, which helps you to be safe with certain things - the way they move around, like in an aquarium, swimming very slowly. He uses the top of the proscenium as much as he uses the bottom. It felt like waking up on an airplane in the middle of the night: you're going across the country and you just wake up a little bit, and everyone in the plane is asleep, and you just hear the "shhhh" and you go ding, and the stewardess comes over with a Coca-Cola, and you look out the window and you don't know where you are; there's clouds, there's some light, and you don't care that you don't know where you are. You're safe in not knowing. It's Texas in Berlin. It's Aunt Jemimah and Max Schmelling doing the cha-cha-cha.

FT: What was it like working with Jack Nicholson in Ironweed?

TW: He comes into the trailer with a tape, a little cassette, of his favorite music. A little Billie Holiday, a little Robert Johnson, the '60s groups, albums that never came out, some obscure stuff - it was a great compilation. We were all listening and reading Weekly World News and the Enquirer. It was in the morning, and everybody's saying "This is nice" Jack was sitting, getting his hair done or whatever, and everybody had forgotten that he had provided us with his favorite selections. And at one point everybody was clapping along with the music, and Jack stood up, turned the music down, put his arms in the air, and said, "Jack's tapes." What I liked about that is that you're not listening to Robert Johnson, you're listening to "Jack's tapes."

His other famous expression was "Continuity is for sissies." If anybody got too fussy about hair or makeup, he'd say. "Wait a minute, continuity is for sissies" I love that. Frenchie in the makeup trailer got in a big argument with him about where the best place to live is. She said. -"Oh, Paris, of course, you know. Paris is so cultural." And he said. "The West is the best, babe." He said, ' I've never been in Paris, but I have admired it from from a few oblique angles." And he gave me one of those eyes like, "You know what I mean?"

FT: Well, what about Nicholson as an actor?

TW: He relaxes his butt, and when his butt's relaxed, he's so central, he doesn't miss a thing going on in a room. When somebody else is working and he's off camera, he'll go. "Look at old Jeff working out there." He's always doing that because he's a real big fan.

FT: You also worked with Meryl Streep in Ironweed.

TW: She said she based her character, Helen, on the treble clef. I like that. The shape-like a quail, only with its head tacked in a little bit. Her preparation and commitment and concentration within the characters are devastating.

FT: Which actors would you like to work with? Don't you and Nick Cage do a Jerry Lewis routine?

TW: Yeah, Nick loves Jerry Lewis. Nick has been an inspiration to me as an actor because he's such an innovator. He's somewhere between Zorro, Jerry Lewis and Elvis. He's an inventor and he's fearless.

FT: You've been asked by several musicians to produce their albums.

TW: I've been asked by several good young groups. I don't know. because it takes a lot of commitment and you're helping somebody go through this whole kind of nervous Lamaze experience with their music, and you really gotta have clean hands. So it makes me nervous. I haven't done it yet. I'd like to.

FT: You've always loved Bob Dylan and he spoke very highly of you in that Biograph album(14). If he ever approached you to work with him on an album, would you?

TW: Oh Christ, yes.

FT: Much of Swordfishtrombones - the sound, the instrumentation, the song styles, even the record cover - was a bold departure from anything you'd done before. What impelled you to do that?

TW: I don't know. It's like the moles underneath Stonehenge; that's one of the largest mole communities on the globe, and they have a whole hierarchy there. They actually salute moles who have had the courage to tunnel beneath great rivers, because of the risk involved. If you make one bad move, you bring the whole river back up to the tunnel and wipe out a whole community. They also have punishments for those who have done that.

FT: In ancient Greece they tried you if you were too adventurous with their music system.

TW: You could go to jail for that.

FT: Yeah, that's a Harry Partch story(15) . He talked about Timotheus. Who was banished from a city because he added two strings to a three-string lyre, and Partch says. "My lyre has seventy-two strings, and I shudder to think what would have happened to me in ancient Greece."

TW: God, they would have boiled him.

Notes:

(1) Worked as a doorman at a local nightclub: Further reading: The Heritage

(2) His fabled stint at the Tropicana Motel: Further reading: Tropicana Motel.

(3) A new musical drama in Munich: that would be The Black Rider at the Thalia Theatre in Hamburg/ Germany

(4) I had a friend who lived in a trailer van: Similar story as told in 1993: Tom Waits: "I have learned a great deal about music from other musicians, and from listening to the world around me. But when I was a kid growing up in Whittier, there was a red-headed boy named Billy Swed(1) who lived with his mom in a trailer by the railroad tracks. Billy is the one who taught me how to play in a minor key. Billy didn't go to school. He was already smoking and drinking at the age of 12, and he lived with his mom at the edge of a hobo jungle on a mud rain lake with tires sticking up out of it. There was blue smoke, dead carp, and gourds as big as lamp shades. You could get lost trying to find their place--through overgrown dogwood and pyrancantha bushes, through a culvert under a freeway, and through canyons littered with mattresses and empty paint cans. While Billy taught me how to play, I noticed that he liked to draw on his jeans with a pen. Every inch was covered with these strange forbidden hieroglyphic tattoos that I was constantly trying to decipher. I was certain it was his own musical notation and that he had hundreds of songs written on his pants. Billy's mother was enormous. I would look at her and then at the door to the trailer, and then back to her, and faced my first real math problem. How could Mrs. Swed ever get through that door? As an eight-year-old, I remember thinking that Mrs. Swed was like a ship in a bottle and she would never be able to leave. Somehow the trailer, the swamp, and Mrs. Swed all came out of Billy's guitar in a minor key. It was New Year's Day after a week of heavy rain when I went back to their spot to see them again, but Billy and his mom were gone. But the secret knowledge of the chords he taught me was to outweigh all I learned in school and give me a foundation for all music." (Source: "Tom Foolery: Swapping Stories With Inimitable Tom Waits" Buzz Magazine (USA). Date: May, 1993)

(5) I had a Cleveland Greyhound silver trumpet: This might actually be true. There's also an early cover of "Music World" magazine (June, 1973) with Waits holding a trumpet.

- Q (1973): Did you always want to be a musician? TW: "Yeah, I guess so, I couldn't think of anything else I really wanted to be, seems to be today nobody wants to be anything but, nobody wants to be a baseball player anymore or anything - everybody wants to be a rock n roll star. I was always real interested in music, it never really struck me to write until I guess about the late 60's, about '68 or '69 I started writing, up until then I just listened to a lot of music, played in school orchestras, played trumpet in elementary school, junior high, high school, went through all that and hung around with some friends of mine that played classical piano and picked up a few little licks here and there, played guitar and stumbled on the Heritage." (Source: "Folkscene 1973, with Howard and Roz Larman" (KPFK-FM 90.7). Date: Los Angeles/ USA. August 12, 1973)

- TW (1985): "I played the trumpet when I was a kid, but I gave it up. I like it because it was easy to carry. It was like carrying your lunch. A piano, you have to go to it. You never hear anybody say "Pass me that piano, buddy."" (Source: "The Beat Goes On". Rock Bill magazine (USA). October 1983, by Kid Millions)

- TW (1985): "I played the bugle at school. When the flag was raised in the morning and lowered in the afternoon. That happens every day at every school in America. Da-da-DA. I can still remember the smell of that bugle case. Bad eggs and a stale T-shirt." (Source: "Dog Day Afternoon" Time Out magazine (UK), by Richard Rayner. Date: New York, October 3-9, 1985)

- TW (1987): "A Cleveland Greyhound (trumpet). It was a silver trumpet, and I played taps at the end of the school day and got there early and played reveille as the flag went up." It was the first and last instrument on which Waits took lessons. From cheap Mexican guitars he moved on to the piano--and from playing Jerome Kern and George Gershwin he moved on to playing around with music of his own." (Source: "Tom Waits Makes Good" Los Angeles Times: Robert Sabbag. February 22, 1987)

- JS (2003): "Tom Waits allowed that trumpet was his first instrument and that playing bugle for the Cub Scouts was his first gig." (Source: "Raitt, Waits, Buffalo jam with S.F. schoolkids" Joel Selvin, Chronicle Senior Pop Music Critic. Thursday, October 23, 2003. San Francisco Chronicle)

(6) I hitchhiked to Arizona with Sam Jones:

- Tom Waits (1999): "I have slept in a graveyard and I have rode the rails. When I was a kid, I used to hitchhike all the time from California to Arizona with a buddy named Sam Jones. We would just see how far we could go in three days, on a weekend, see if we could get back by Monday. I remember one night in a fog, we got lost On this side road and didn't know where we were exactly. And the fog came in and we were really lost then and it was very cold. We dug a big ditch in a dry riverbed and we both laid in there and pulled all this dirt and leaves over us Ike a blanket. We're shivering in this ditch all night, and we woke up in the morning and the fog had cleared and right across from us was a diner; we couldn't see it through the fog. We went in and had a great breakfast, still my high-water mark for a great breakfast. The phantom diner." ("The Man Who Howled Wolf" Magnet magazine, by Jonathan Valania. Astro Motel/ Santa Rosa. June-July, 1999).

- Tom Waits (2002): "I had some good things that happened to me hitchhiking, because I did wind up on a New Year's Eve in front of a Pentecostal church and an old woman named Mrs. Anderson came out. We were stuck in a town, with like 7 people in this town and trying to get out you know? And my buddy and I were out there for hours and hours and hours getting colder and colder and it was getting darker and darker. Finally she came over and she says: "Come on in the church here. It's warm and there's music and you can sit in the back row." And then we did and eh. They were singing and you know they had a tambourine an electric guitar and a drummer. They were talking in tongues and then they kept gesturing to me and my friend Sam(10): "These are our wayfaring strangers here." So we felt kinda important. And they took op a collection, they gave us some money, bought us a hotel room and a meal. We got up the next morning, then we hit the first ride at 7 in the morning and then we were gone. It was really nice, I still remember all that and it gave me a good feeling about traveling." (Source: ""Fresh Air with Terry Gross, produced in Philadelphia by WHYY" radio show. May 21, 2002)

- In Waits' 1974 press release for The Heart Of Saturday Night a Sam Jones is listed as one of his favourite writers. Sam Jones is also name checked in "I wish I was in New Orleans" (1976) "And Clayborn Avenue me and you Sam Jones and all." He's also mentioned on the booklet of the album "Nighthawks at the diner": "Special thanks to Sam (I'll pay you if I can and when I get it) Jones.

(7) The first time I heard Puccini's Nessum Dorma: "Nessum dorma," from Puccini's 'Turandot':

- Tom Waits (1983): "Coppola is one of the most interesting people I have ever met. He's very obsessed and has a great sense of family and loyalty, but his real mistress is film, images and drama. He's the first one who ever interested me in opera, something I never dreamed of ever being interested in. He played me a Puccini aria called 'Nessun Dorma' and it just undressed me, I became unwrapped." (Source: "Swordfish Out of Water: Tom Waits" Sounds magazine by Edwin Pouncey. November 15, 1983)

- Tom Waits (1999): "I heard "Nessun Dorma" in the kitchen at Coppolas with Raul Julia one night, and it changed my life, that particular Aria. I had never heard it. He asked me if I had ever heard it, and I said no, and he was like, as if I said I've never had spaghetti and meatballs-`Oh My God, O My God!' and he grabbed me and he brought me to the jukebox (there was a jukebox in the kitchen) and he put that on and he just kind of left me there. It was like giving a cigar to a 5 year old. I turned blue, and I cried." (Tom Waits, Artist Choice/ HearMusic: October, 1999)

(8) Buffalo Bob and the Howdy Doody Revue: First mentioned in the self written press biography for The Heart Of Saturday Night (1974). Howdy Doody (w. Buffalo Bob, born Robert Schmidt on November 27, 1917) was one of the first American television shows for children. In 1947, NBC brought The Howdy Doody Show to television sets across the US. The TV show went off the air in 1960. From 1970 to 1976 Howdy Bob toured with his show and made hundreds of appearances across the US. There's no confirmation Waits actually ever opened one of these shows. It's still a great story... Buffalo Bob died in 1998 at the age of 80.

- David Fricke (1999): "The gig with Fifties TV star Buffalo Bob and his marionette, Howdy Doody, was a double whammy: at 10 A.M., in front of housewives and kids. "I wanted to kill my agent. And no jury would have convicted me," Waits says, only half-kidding. "Bob and I didn't get along. He called me Tommy. And I distinctly remember candy coming out of the piano as I played. "Jesus," he sighs. "That's when you need the old expression, 'You gotta love the business.'" (Source: "The Resurrection Of Tom Waits", Rolling Stone magazine (USA), by David Fricke. June 24, 1999)

(9) Bette Midler attended some of your earliest New York concerts: those concerts would be at The Bottom Line (New York/ USA): April 22-23, 1975 (opening for Peter Bergman & Phil Proctor of the Firesign Theatre).

- Bette Midler (1978) on meeting Tom Waits in 1975: "My idea of a good time in L.A. is to go to the Fatburger with Tom Waits. Fact, Peter Riegert and I schlepped him over there last night for fries and a malted. "The Fatburger is a local junk-food pit, and Tom Waits is - do you know Tom Waits? - oh, he's won-der-ful. I first ran into him at the Bottom Line in New York. He was singing 'The Heart of Saturday Night.' and I just fell in love with him on the spot. "We got passingly acquainted that first night, and then I ran into him out here someplace, and I suggested we get together for a visit. Tom lives ... well, sort of knee-deep in grunge, so he was reluctant for me to see his apartment. I grew up in lots of clutter myself, and delicate I ain't, so I kept after him till he finally invited me over. He acted ultra-shy at first, but he finally ushered me around, and he's got his piano in the kitchen, and he only uses the kitchen range to light his cigarettes, and then there's this refrigerator where he keeps his hammers and wrenches and nuts and bolts and stuff like that. He opened the fridge door and with an absolute poker face he said, 'I got some cool tools in here.' You ever hear a cornier line than that? I howled for an hour, and we've been buddies ever since. "Tom can always get me tickled, and he really helped jack up my spirits after the disaster of that gay-rights benefit in Hollywood." (Source: "Bette Bounces Back" Bette and Aaron: One Sings, The Other Doesn't. Grover Lewis. New West: March 13, 1978). Further reading: Anecdotes

(10) Rainbow Sleeves: though "Rainbow Sleeves" was only recorded by Rickie Lee Jones ("Girl At Her Volcano" Warner Bros, 1983), Waits claims he originally wrote it for Midler:

- Tom Waits (1985): "Yeah, that was written for Bette Midler. She did it on the road, and then on a TV show once. Bette's one of my oldest friends. She's a real touchstone for me." (Source: "The Marlowe Of The Ivories" New Musical Express magazine (UK), by Barney Hoskyns. Date: May 25, 1985)

(11) After hours in a club in Copenhagen: that must have been during or after the show of October 31, 1985: Falke Halle. Copenhagen/ Denmark (Rain Dogs tour). In 1993 Waits told the same story, changing Copenhagen into Holland.

- Tom Waits (1993): "He (Marc Ribot) also gets himself whipped up into a voodoo frenzy. He gets the look in his eye that makes you want to back off. Y'know? It's like, "goddamn!" We were in some after hours place in, I dunno, Holland, in the corner, there was no stage, it was a club with normally no live music. We just got into the corner and plugged in and started to play. And everybody just pushed the tables and chairs back and it was real wild. And Ribot banged into a speaker box, and there was a bottle of Vat 69 on it, and it tipped over, and it was full, and it just kept spilling out onto the floor, and he was getting under the stream of liquor, which was splashing onto the floor, and liquor was going everywhere, and you looked at his face and it was like an animal, he'd been, like worked up--." (Source: "Tom Waits Meets Jim Jarmusch" Straight No Chaser magazine Vol. 1 Issue 20 (UK), by Jim Jarmusch. Date: October, 1992 (published early 1993))

(12) The Seven Dwarfs' work song "Heigh-Ho": Stay Awake (Interpretations of Music from Vintage Disney Films). Various artists. December, 1988 Label: A&M Records (A&M CD 3918 DX 003644). "Heigh Ho - The Dwarfs' Marching Song" (first release). Re-released on Orphans, 2006. Read lyrics: Heigh-Ho

(13) It was called a "cowboy opera": that would later turn out to be The Black Rider. Further reading: The Black Rider

(14) He spoke very highly of you in that Biograph album: unknown/ unidentified album

(15) That's a Harry Partch story: San Diego multi-instrumentalist. Developed and played home made instruments. Released the album" The World Of Harry Partch". Major influence for the album 'Swordfishtrombones'. Partch died in San Diego, 1974. Further reading: Partch, Harry 1; Partch, Harry 2; Partch, Harry 3;