|

Title: Tom Waits & Robert Wilson's Alice Source: The Late Show. BBC TV documentary. Presented by Beatrix Campbell. Aired March 4, 1993. Camera, Robert Payton. Sound, Bruce Wills. Production Assistant, Maggi Gibson. Editors, Mike Duly, Tamra Ferguson. Director, Mark Cooper. Transcription from tape by "Pieter from Holland" as published on the Tom Waits Library Date: aired March 4, 1993 Keywords: Alice, Robert Wilson, Poor Edward Picture: Beatrix Campbell |

Tom Waits & Robert Wilson's Alice

Beatrix Campbell: [in the studio] Robert Wilson is one of America's foremost theatre directors. (..?..) his native country and in Europe but on the scene in Britain, where a naturalistic stage tradition remains mistrustful of his vision of theatre and spectacle. Wilson thrives on collaboration, especially with composers and musicians. Among them Philip Glass, David Byrne and Jessye Norman. His latest pairing is with singer songwriter Tom Waits. And it's his most surprising. While Wilson's theatre is minimalist and formal and indebted to expressionism, Waits' music is shot through with dirt, noise and good old romanticism. Their first musical collaboration in 1990, The Black Rider(1), was a huge hit all over Europe. A few months ago Waits and Wilson reconvened at Hamburg state funded Thalia theatre to create Alice(2), based loosely on Lewis Carroll's Victorian classic. Alice is a surreal musical exploration of the relationship between the author and the real child who inspired him. The Late Show's Mark Cooper went to Hamburg to see what these American visionaries had made of an English literary heirloom.

[Waits at the Piano(3): performs "There's Only Alice"]

[Footage of December, 1992 theatre preview at the Thalia Theatre: actors performing "There's Only Alice"]

Mark Cooper: Moving between the fantasy world of "Alice In Wonderland" and the real life relationship between its author Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell, the child from whom he drew his heroin, Alice is a collaboration between director Robert Wilson, songwriter Tom Waits and writer Paul Schmidt.

Robert Wilson: I don't know, maybe it's because we're both from the Mid-West or.. I don't know, we're very different men, different lifestyles, different esthetics, we dress differently. Even our ideas about art are quit different. I'm a little more formal and cooler and he's a little freer. But somehow it works together. I think that our work's, that our work is stronger together then it is separate. Because we are different, we are counterpoints.

Tom Waits (at the piano): I think the best collaboration is really the uh, is the uh, the blind crippled midget on the shoulders of the sighted giant. So, I guess Wilson's the uh sighted giant and that I'm uh the crippled midget.

Paul Schmidt: They both got their extremes, I mean when they got this collaboration I sat in the middle between America's greatest minimalist and America's greatest maximalist, (laughs) between Wilson and Waits and that's the tension that I think works.

[Footage of Waits performing "Tom Traubert's Blues": from The Old Grey Whistle Test, BBC-2, 1977]

Mark Cooper: Tom Waits released his first album Closing Time in 1973. He quickly distinguished himself from other singer-songwriters of the period, with his beat, jazz and Tin Pan Alley influences, the romantic richness of his lyrics and his gravel voice delivery. During the last decade Waits' music has grown steadily dirtier, his arrangements and instrumentation(4) ever wilder.

[Footage of Waits in the studio, and video clip for "I Don't Wanna Grow Up", 1993]

Mark Cooper: Robert Wilson emerged from the avant-garde theatre of New York in the late sixties.

[Footage from: A Letter From Queen Victoria, 1974]

John Rockwell (European Arts correspondent, New York Times): Robert Wilson's theatre consists of images, rhythm, spirituality, and collaboration. I think he derives enormous emotional import from pictures and light, stage pictures and light. He is without question the leading master and inspirer of what one might call imagistic theatre or, what has been called in a book about Wilson, the theatre of visions.

[Footage from: Einstein On The Beach, 1976]

Mark Cooper: Wilson achieved international fame with a collaboration with Philip Glass, Einstein On The Beach. This 4-hour production was revived last year and toured the world to renewed acclaim. In 1990 Wilson teamed up with fellow Americans Tom Waits and William Burroughs for The Black Rider, a musical extravaganza based on an old German folktale. The Black Rider was mounted with the repertory company of Hamburg's Thalia Theatre.

[Footage from The Black Rider at the Thalia Theatre: Hamburg, 1990]

Mark Cooper: The Victorian cleric Charles Dodgson, penname Lewis Carroll, was also a mathematician, poet and photographer. He frequently photographed Alice Liddell, the inspiration for the Alice books. These photographs and his diaries reveal a man obsessed.

Paul Schmidt: One of the things that we started with, was the notion of Dodgson as a photographer. We know he took pictures of little girls, that's what he liked to do. And when you think of the image of what a camera was in those days. Those enormous boxes with the long snouts sticking out in front of them, the lens and the great black cloth from the photographers head. And the braces that people had to sit in, to hold the pose. It must have been a terrifying experience. It might have been a terrifying experience for a young child.

[Footage of December, 1992 Alice theatre preview at the Thalia Theatre: Alice in front of the camera]

Paul Schmidt: One of the things we were trying to do was to balance to take the character of Dodgson and portray him first as the photographer as this slightly uninnocent figure, and then the second part is the White Knight, from the second Alice book, from "The Looking Glass", which is clearly, which Dodgson means as a portrait of himself, and is one of the most wonderfully gentle old people in literature. So it was trying to show that relationship of how a world of grown ups can scare children and threaten children, and at the same time that it's love and it means to be love.

[Footage of December, 1992 Alice theatre preview at the Thalia Theatre: "Fish And Bird"]

Robert Wilson: There are various levels of the narrative. There's the text by Paul Schmidt, which is one thing, and you have the lyrics of Tom which are another. And they're sort of counterpoints and sometimes it's like a grid or something, that can be lined out so that the visual imagery or this visual story is lined up with Paul's text and Tom's music. And sometimes they're like grids that are going out of phase, and sometimes they line up. But often they're sort of counterpoints to one another.

[Footage of Alice rehearsals]

Tom Waits: That's the great thing about the workshop, you can go and get inspired and watch what Bob does up stage, watch what the actors do, and I come every day with maybe a few new songs and find out how they work. The theatre is uh. you realize why they call it "the fabulous invalid". You have to get it to stand up. Bob wants everybody to do it: "Do it, do it right now. Whadda ya got?"

[Waits at the piano: performing "Jabberwocky"]

John Rockwell: Waits', if you will, American music, serves as a kind of., the moment in which the pretences and the denials and the self-deceptions drop away and true emotional, this is true for the ballads, as far as the carnival bumptiousness and the rockiness is concerned, uh I don't know. You could argue that there's a circus element to Alice herself, to the stories to the very nature of these fantastical characters that is mirrored in that kind of music.

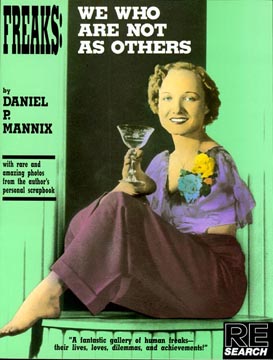

Tom Waits: We were trying to make the song text a different, some different things one would normally associate with "Alice In Wonderland". So, oh we did some things. We had a song called "Poor Edward"(5) which is a true story actually. I took the same melody of "Alice" and. There's a true story about it [takes out a book](6)... a circus freak that was uh born with a woman's face on the back of his head [tries to find the article in the book]. Uh, sorry girls.. ooh. oooh!

Paul Schmidt: A lot of fun fairs that I know of in America are called Wonderland. You get that all the time. It seemed to me it was kind of a natural connection. And the other interesting thing that Tom really found, was sort of the underside of Victorian life, I mean we think of proper Victorian England, but you look at some of the freak shows and things that grew up in the nineteenth century, it was sort of a darker underside of it. And that's where a lot of Tom's images plug in beautifully. I think they really reflect terrifically, there was a tension between some of those images and the surface innocence of the Alice story.

Tom Waits: [still trying to find the article on Poor Edward] Anyway I'll just tell it. Uhm, poor Edward. He came from a very wealthy family and he was, you know, heir to a big fortune and, but he had this curse and he said that the face on the back of his head was his devil twin, and it spoke to him at night. And ultimately he couldn't take it anymore and he went and checked into a hotel and hung himself. So. I used that as an idea for a song for the play because I feel in any kind of obsession you feel like you are attached to somebody. And that to separate you, would kill you both. And so uh, that's what the song is about. [plays "Poor Edward" at the piano]

Mark Cooper: Wilson has been called a theatre-artist. And he begins all his productions by drawing and sketching and even sculpting. The staging of Alice is based on these preliminary artworks. The shape, structure and look of each scene begins for Wilson with a precise visual image.

[Shots of Alice curtains and actors performing: "Everything You Can Think Of Is True"]

Robert Wilson: Well I don't try to analyze it. I don't think about it psychologically. Usually it rings a bell to me and then I say: "Okay, that's enough." And I trust my intuition. It usually seems right, I think it's right. Martha Graham said once, the American choreographer, she said: "The body doesn't lie." So I think that sometimes if you're insecure about what to do, if you just sort of close your eyes and take a breath and say: "Shall I do this, or shall I do that? Mmm this seems right." It's usually the right thing.

Annette Paulmann: Bob doesn't talk a lot about his work. He can't explain why he said: "Well you have to enter left and use the stage on right and two minutes and fifty seconds." And if you ask him "Why?" he said: "Do it." So.

Stefan Kurt: Yeah and it's not only formal you know. Most of them say: "Okay you are some sort of robots doing that, and that must be awful to work in that way and." But it's okay. It's very formal and it gives you a structure where you can work with, but you have to fill it by your own and that's. Uh I like it very much.

[Footage of December, 1992 Alice theatre preview at the Thalia Theatre]

John Rockwell: You're dealing with a story which in its outer form is very familiar to Anglo-Americans to what the "Alice In Wonderland" story is. Yet by bringing in the element of the relationship between Dodgson/ Carroll and the historical Alice, exploring it for its kind of psycho-sexual child molestation implications, yet without being censorious about that, and with seeing it as something complex and moving and beautiful if troubled, you add an element which is very moving and emotionally affective. And then by having the final scene being the old Alice in her seventies or eighties reflecting back on this eternal partnership and essentially marriage, uh it adds yet another element.

Tom Waits [at the piano] This is kinda Lewis Carroll. You know he fell on the ice of a pond and he broke his watch one day and he never got it fixed. And he said, that's what happened to him. He said, as long as his watch was broken he could always stay in this world you know, that he invented for him and for her, so.

[Footage of December, 1992 Alice theatre preview at the Thalia Theatre: "You Haven't Looked At Me"]

[Waits at the piano performing "You Haven't Looked At Me"]

Notes:

(1) The Black Rider: further reading: The Black Rider

(2) Alice: further reading: Alice

(3) Waits at the piano:

- Mark Cooper (1999): "Alone, Waits decamped to a small hotel amid Hamburg's filthy strasses to work on the orchestration for a six-week stint, toiling against the clock to make the pre-Christmas opening night and, by all accounts, pining for Californian family life. "It was a pretty fraught time for Tom," recalls Mark Cooper, who directed a short documentary on the production for BBC's Late Show. "When we arrived he was involved in all the fine-tuning and the sheer stress was obviously getting to him. We set up all this gear and lit a piano in the centre of a room, which maybe looked too glamorous. He threw a complete paddy and demanded we shoot him at a broken down, out-of-tune upright piano in the corner of the room. He insisted that we just use the sound from the camera and a single light. Of course he was right--it worked brilliantly. Footage reveals "Alice" to be far more accessible than the harsh and brittle "The Black Rider", with a collection of superb songs exquisitely performed by the Thalia players. "'Alice' was magnificent," summarises Cooper. "It had brilliant music and fantastic ballads presented beautifully by Wilson." (Source: "Tom's Lost Classic". MOJO magazine, Paul Gorman. Sept./ Oct. 1999)

(4) Instrumentation: further reading: Instruments

(5) Poor Edward: aka: "Chained Together For Life". Read lyrics: Poor Edward

(6) Takes out a book: The book Waits is holding is "Freaks: We Who Are Not As Others" by Daniel P. Mannix. This long out of print classic book based on Mannix's personal acquaintance with sideshow stars, holds many names/ stories Waits used in the Black Rider/ Alice. Originally published by Pocket Books in 1976, re-released by RE/Search Books in 1990.

Freaks: We Who Are Not As Others. RE/ Search, 1990