|

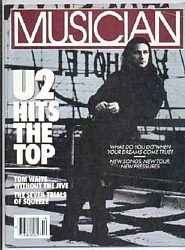

Title: Tom Waits Is Flying Upside Down (On Purpose) Source: Musician magazine (USA), by Mark Rowland. Thanks to Larry DaSilveira for donating article Date: Traveler's Cafe/ Los Angeles. October, 1987 Key words: Franks Wild Years, Musical transition, Voice, Family life, Christianity, Charles Bukowski, Commercials, Copyright, Prince, Commercial success, Jack Nicholson, The Replacements, Studio recording Magazine front cover: Musician magazine (USA), October, 1987 |

| Accompanying picture |

Tom Waits Is Flying Upside Down (On Purpose)

It's always the mistakes," Tom Waits is saying. "Most things begin as a mistake. Most breakthroughs in music come out of a revolution of the form. Someone revolted, and was probably not well-liked. But he ultimately started his own country."

A few years ago, Tom Waits started his own country. Quite literally the born traveler (he debuted in this life from the back seat of a taxi), he proceeded to stockpile the place with the exotic goods of a worldly imagination. A wheezing accordion from a seedy tango palace, blues licks honed on a razor strap. A marimba high jacked to the South Seas during a performance of the Nutcracker Suite. A crusty doughnut from an abandoned flophouse, sloshed down with a German drinking song, or something like that. A thousand and one nocturnal images to make your heart race and your head itch, conjured by a rasping voice on the lam from the Surgeon General. Waits planted one flag called Swordfishtrombones (demarcating latitude and longitude), then another titled Rain Dogs. And while neither has exactly jammed the Voice of America, they're the kind of signposts you like to have around when someone - maybe yourself - starts to wonder if popular music still has the originality or vitality to really matter.

Waits' latest chapter, Frank's Wild Years, first appeared in somewhat altered costume last summer as a one-man opera for the Steppenwolf Theater Company in Chicago. Waits sees it as the end of a trilogy (the album title and central character are taken from a song on Swordfishtrombones}, and, like its predecessors, it's an unusually large collection of tunes (seventeen) that invites neither easy assimilation nor casual dismissal. This is music designed to insinuate itself into your consciousness (the context of a play might quicken the process), but, also like Rain Dogs, the various puzzle parts eventually align themselves into a theme.

To summarize, Frank's Wild Years takes the form of a reminiscence, the story of a guy who decided to let fantasy navigate his life's course (in the original song, he escapes middle-class bondage by torching his house). It's a kind of American Dream. Several songs set the tone for fabulous exploits: the murky excitement of a getaway in "Hang On St. Christopher," a tribal rhumba called "Straight To The Top," a siren song about "Temptation." But Frank's fantasy life turns out to be just that; the presence of a more jarring reality occurs during a reprise of "Straight To The Top" as a pathetic lounge number (it's the twisted Vegas parody Waits fans have long fantasized about) and a truly nightmarish "I'll Take New York," which begins as an unwieldy siege and ends with what's left of Frank's hopes careening down an elevator shaft. By journey's end he's become mournful, drowning his sorrows in weepers like "Cold Cold Ground" and the "Train Song," the latter a minor masterpiece that's as timeless as great gospel. The album's coda, "Innocent When You Dream," sounds like a whisper from the hollows of a broken man's memory. It's a strange, funny and soulful saga, spiced with a cauldron of musical surprises Waits stirs together with shamanistic skill.

He has help. Much of what separates Waits' past three albums from his early career, after all, is the way he's expanded his musical palette, from solo piano man to chief alchemist for a gang of complementary dispositions. Those cohorts include guitarist Marc Ribot, percussionist Michael Blair, bassist and horn arranger Greg Cohen, Ralph Camey on saxophone and William Schimmel on a variety of equipment, from accordion to Leslie bass pedals. Waits' instruments include pump organ, guitar, mellotron, even something called the optigon, but nothing so astonishing as that voice - here marinating a tender ballad, there howling through a circle of hell, finally settling into a familiarly phlegmatic, lung-crunching groove. He'll never have Whitney Houston's pipes, but he's the better singer.

Of all the pop songwriters who have followed in Bob Dylan's footsteps (that is, everyone), few suggest superficial comparison less than Waits. And yet, more than anyone else, he has done the one deed crucial to Dylan's entire mythology: shattered his chosen form despite deep feeling for its traditions, then found his voice by reconstructing shards from the rubble into a new kind of pop musical language. Dylan's "mistakes" set off an instant revolution; that won't happen with Waits, but it's a good bet he's already planted the seeds for future subversions.

Ironically, part of the tradition Waits deep-sixed includes his first seven albums, from 1973's Closing Time through 1980's Heartattack And Vine. It's a period of his career he now seems to view as germinal as best, though it produced a wealth of fine songs, some popularized in versions by more conventional singers (Springsteen's "Jersey Girl," the Eagles' "Ol' 55"(1)), lyrics and melodies spun into webs of deceptively sturdy construction. His former persona - a combination thread of 50s beatnik, 40s vaudevillian, 30s melodist, and so on into the nineteenth century - may seem dated, but that was always deliberate. Along with Waits' deprecating humor and the prevailing wisdom that his face-on-the-barroom-floor theatricality accurately reflected a chosen lifestyle, it had earned him a cult following for life, or at least what was likely to remain of it.

But Waits has always shunned cliches, even tragic ones. Subtly at first, he found escape hatches from encroaching stereotypes. His work began to include movie scores (such as the underrated One From The Heart, which included duets with Crystal Gayle, of all people) and film appearances - Rumble-fish, Cotton Club and most notably Jim Jarmusch's Down By Law. He has a role opposite Jack Nicholson in the forthcoming film adaptation of William Kennedy's Pulitzer-winning novel Ironweed. In 1980 he married Kathleen Brennan; they've since become songwriting partners. (She co-wrote the libretto for Frank's Wild Years and collaborated on several of the songs.) They have two children.

Tom Waits recently sat down for talk and a few beers in one of his favorite joints, the Traveler's Cafe. A Filipino coffee shop and bar not far from downtown Los Angeles, it's the kind of place that looks closed even after you walk inside. We settled into a weathered booth, as far from the light of afternoon as the middle of a Trader Vic's, though these surroundings emanated considerably more warmth and raffish charm.

The same could be said for Waits. Attired in a black leather jacket, nondescript gray shirt and day-old stubble, he looked and occasionally played the role of house raconteur; as anyone who's followed his career knows, he's a fine storyteller and a funny guy. But he also leavened the humor with insightful observations that, beneath the wisecracking surface, suggested a core of emotional vulnerability and generosity of spirit. He's not the sort you'd presume to "know" after one or two encounters, but it's clear the music of Tom Waits has acquired its special character in large part because he has character. The best mistakes require no less.

MUSICIAN: Your approach to music has changed dramatically over your last three albums, beginning with Swordfishtrombones. Can you reconstruct that transitional period?

WAITS: I don't know if I can reconstruct it really - it wasn't religious or anything. You get to an impasse creatively at some point, and you can either ignore it or deal with it. And it's like anything, you go down a road and... hopefully, there's a series of tunnels. I'd started feeling like my music was very separate from myself. My life had changed and my music had stayed pretty much its own thing. I thought I had to find a way to bring it closer. Not so much with my life as with my imagination.

MUSICIAN: Was it also a matter of getting more confident?

WAITS: Not so much [with] subject matter. I mean, my voice is still a barking dog at best. You get a little taller, you see a little further; you grow up. Hopefully we all keep growing. That sounds a little corny but... you have to decide whether you're going to give this up and start working in the salt mines, or take chances. I never take the chances that I would really like to, if I had more courage. But it's a beginning.

MUSICIAN: Have the results surprised you?

WAITS: No, I knew who I was working with. You surround yourself with people who can know when you're trying to discover something, and they're part of the process. Keith Richards had an expression for it that's very apropos: He called it "the hair in the gate." You know when you go to the movies and you watch an old film, and a piece of hair catches in the gate? It's quivering there and then it flies away. That's what I was trying to do - put the hair in the gate.

MUSICIAN: You've said that when you're writing you'll sometimes put together words by feeling, and later understand why they fit. Do you put together your music that way, or are you following through a fairly concrete plan?

WAITS: It's like when you're in a film and you see where the camera is, and then invariably one will look to the left out of the frame and see something infinitely more interesting. That's what I try to look out for. It's not a science. It's like when you hear music "wrong" or when you hear it coming through a wall and it mixes in - I pay attention to those things. That's the hair in the gate. You can't always do it, and sometimes it's just distraction. Other times it's imperative that you follow the rabbit, and roll.

MUSICIAN: Do you feel by now you've got control of your voice? I don't mean literally your voice, but your ability to communicate.

WAITS: You always work on your voice. Once you feel as though you have one, whatever you tackle will come under the spell of what you're trying to do. You want to be able to make turns and fly upside down - but not by mistake. You want it to be a conscious decision, and to do it well. You don't want somebody to say, "Well, he went for the bank there and lost control and he went right into the mountain and thirty-seven people died." You want 'em to say, "Well, he decided to take his hands off the controls and sacrifice the entire plane and its passengers. And I must say it was a spectacular flight. The explosion set off sparks that could be seen all the way to Oxnard. Remarkable." I think you have to work on yourself more than you work on the music. Then whatever you're aiming at you'll be able to hit between the eyes.

MUSICIAN: You did wait a long time before taking your musical leap. So maybe that was a crucial part of the process.

WAITS: It's strange. It's all a journey. You don't know where it's going to take you, the people that you meet and the changes your life will bring. I can say I wished I'd jumped off earlier, but I don't know if I actually jumped off anything or else, you know, just redecorated. But I know that the last three records are a departure from what I was doing; I'm very aware of that. I don't write the same way. I used to sit in a room with a piano, the Tin Pan Alley approach. I thought that's how songs were written.

MUSICIAN: That's how songs were written.

WAITS: Yeah, you go to work and write songs. I still do that, but now sometimes I break everything I've found. It's like you give a kid a toy and they play with the wrapping. I do that now.

MUSICIAN: Forty years ago the kind of music you played might be more or less dictated by where you grew up.

WAITS: You think you're a victim of your musical environment. To a degree you are.

MUSICIAN: But now it's different. You have access to everything, and what you lose are your roots.

WAITS: Your world is only as large as you make it. What you decide to include and to affect you is very much up to you. What you ultimately do with it is something else. It's like the blind men describing the elephant, you know? "It's a small apartment, it's a trailer, it's a large billfold." As far as influences, it takes a long time for something to find its way into what you do. You have to plant it, water it, let it grow. You know where they say in Genesis that man was made from clay(2)? Now they're saying that clay, genetically, contains all the information of every life form. It's all in the clay. You hit it with a hammer, a light comes from it. They've done experiments with Egyptian pottery made on a wheel thousands of years ago - they play the plates backwards and receive a recording, a very primitive recording of what took place in the room. Your ghosts. So, I'll buy that.

MUSICIAN: So you have to search for your roots, in the right places.

WAITS: The first stroke is always the most important. Kids do that. I watch kids draw and go, Jesus, I wish I could do that. I wish I could get back there. I wish I could go through the keyhole. You become very self-conscious as you get older, and less spontaneous, and you feel very victimized by your creative world, your creative person.

MUSICIAN: What can you do about it?

WAITS: You try and work on it. With music, I mean, some people believe you're cutting off a piece of something that's alive. It's like the guy who had a prize pig with all these bandages over it. And his neighbor asks, "What happened to the pig?" The first guy says, "I use it for bacon. I can't kill such a beautiful pig, I just take a slice off him now and then. "So, you don't want to kill the pig.

MUSICIAN: The way you describe it, it seems the process of growing as a musician - or anything - is about finding the doors that let you out of the boxes you put yourself in. And inevitably you're dissatisfied in retrospect no matter what you do.

WAITS: That's just human nature. Somebody has to take it from you, just to allow it to dry. The process of "mixing" makes me insane. I feel like I'm underwater without scuba gear.

MUSICIAN: So who finally puts the cork in the bottle?

WAITS: I do. Or my wife hits me with a frying pan.

MUSICIAN: On Frank's Wild Years you two collaborate on several songs. Did that require much adjustment on your part?

WAITS: It's good. She's very unself-conscious, like the way kids will sing things just as they occur to them. It was

chemistry. I mean, we've got kids. Once you do that together, the other stuff is simple.

MUSICIAN: Has family life changed your outlook?

WAITS: No, but if you don't get that bug off the back of your seat he's gonna go right down into your pocket, [smiles] That's what I like about this place.

MUSICIAN: It's been a favorite of yours for a while. But you moved to New York while making Rain Dogs. Where are you settled now?

WAITS: I don't know where I'm living. Citizen of the world. I live for adventure and to hear the lamentations of the women... I've uprooted a lot. It's like being a traveling salesman. People sit at a desk all day - that's a rough place, you know? I've lived in a lot of different towns. There's a certain gypsy quality, and I'm used to it. I find it easy to write under difficult circumstances and I can capture what's going on. I'm moving towards needing a compound, though. An estate. But in the meantime I'm operating out of a storefront here in the Los Angeles area.

MUSICIAN: It seemed you were living on the edge more during the early 70s, in a physical sense. That you've become more settled. Do you worry how that might affect your inspirations?

WAITS: It's never been settled - my life is not what I would call normal or predictable. But yeah, you think about it because what's going on becomes the reservoir for your stuff. You want details? When I was living in New York it was a very insane time. But these songs [Frank's Wild Years] were written to be part of a story.

MUSICIAN: Did you sense certain parallels between Frank's life story and your own?

WAITS: No, it's just indicative. A drawing that maybe a couple of people would know where those things match up. Your friends and family know, it's a record of something, but not a photograph.

MUSICIAN: Your father's name is Frank. Is that a coincidence?

WAITS: My dad asked me the same thing. Well, Frank did have his wild years. But this is not verbatim. My dad's from Texas. His name is actually Jesse Frank, he's named after Jesse and Frank James. When you came to California in the 40s it was a lot hipper to be named Frankie, after Frank Sinatra, than to go with Jesse - they think you're from the dust bowl. "What did you get here in, a Model A?" But no, Dad, it's not about you.

MUSICIAN: Frank lets fantasies rule his life, but without any direction or sense of reality his life becomes very self-destructive.

WAITS: The laws that govern your private madness when applied to the daily routine of living your life can coagulate into a collision.

MUSICIAN: His "Train Song" is like a mourn of regret, it says, "I ruined my life." And then "Innocent When You Dream" is there to soothe the pain.

WAITS: Well, that's where it starts. When you're young you think everything is possible and that you're in the sun and all that. I always liked that Bob Dylan song, "I was young when I left home and I rambled around and I never wrote a letter to my home, to my home. Never wrote a letter to my home." You don't always know where you're going till you get there. That's the thing about train travel, at least when you say goodbye they get gradually smaller. Airplanes, people go through a door and they're gone. Very strange. They say now that jet lag is really your spirit catching up to your body.

MUSICIAN: So much of the record deals with dreams; they're mentioned in the songs, and the music itself has a dream-like quality. Is that where some of the album came from?

WAITS: Real life, you know, it's very difficult. These are actually more like daydreams. And sometimes a song may find you and then you find it.

MUSICIAN: "Innocent When You Dream" is a centerpiece of the record and suggests that dreams are a source of rebirth.

WAITS: Sure to be a Christmas favorite. Wait'll you get the promotion guys out on the road with that one.

MUSICIAN: Well, it does have a religious quality. And a love of mystery. The music brings that together: The search for mystery is implicit in the sound of the music, and it takes on the aura of a spiritual quest. Not to solve the mystery, but to find it.

WAITS: Let's face it, all of what we know to be religious holidays fall on what were pagan ritual celebrations. I don't want to get out of my area here, but Christianity clearly is like Budweiser: They came in, saw what the natives were doing, and said, "We're gonna let you guys do the little thing with the drums every year at the same time. You're working for Bud now. Don't change a thing. The words are gonna be a little different, but you'll get used to that. We're gonna have to get you some kind of slacks though, and a sports jacket. Can't wear the loincloths anymore. These are fine, they're more comfortable." I don't want to oversimplify. I do believe very much in Billy Graham and all the real giants-

MUSICIAN: Of the industry-

WAITS: They're like bankers. They understand the demographics, and they feel the country like a giant grid, or a video game. Same way politicians do. But even magic tricks were originally designed to get people to understand the magic of the spirit. Turning wine into water: It's the old shell game.

MUSICIAN: And that aspect is a wonderful thing, I think; it puts you in touch with the idea of mystery, the unknowable.

WAITS: In this country we're all very afraid of anything that isn't shrink-wrapped with a price on it, that you can take back to the store if you don't like it. So we've pretty much killed the animal in capture.

MUSICIAN: But your music tries to convey that mystery, as voodoo did, or still does, I suppose, in certain places.

WAITS: Yeah. My dad wanted to have a chicken ranch when I was a kid. He's always been very close to chickens. Never happened, you know, but he has twenty-five chickens in the back yard. And my dad was saying there are still places, down around Tweedy Boulevard in south-central L.A., where you can buy live chickens, and most of the business there is not for dinner. It's for ritual. Hanging them upside down in the doorway for, uh...I don't know a lot about it, but at a certain level you get music - the Stones know all about that. You know that tune on Exile On Main Street, "I Just Want To See His Face." [laughs] That will put you in a spell.

MUSICIAN: You seem attracted to that side of life, though; the seediness of "9th & Hennepin," or the world of Nighthawks At The Diner, or Western Avenue the way Charles Bukowski describes it.

WAITS: I haven't been around 9th and Hennepin in a while, and I only know these things from my own experience. Though I think there must be a place where it all connects. I like where Bukowski says - I'm not quoting exactly - "It's not the big things that drive men mad. It's the little things. The shoelace that breaks when there's no time left." It makes it very difficult for me to drive, you know. 'Cause I'm always looking around. It makes for a very dangerous ride with the family.

MUSICIAN: Do you feel you can impart lessons from your life's experience in a song?

WAITS: You can learn from songs. If you hear it at the right time; like everything else, you have to be ready or it won't mean much. Like going through someone else's photo album.

MUSICIAN: Or if you're in a bad love affair, all the songs on the radio suddenly achieve profundity.

WAITS: Sometimes when I'm really angry at somebody or if I'm in line at the Department of Motor Vehicles, I try to imagine people that I want to strangle; I imagine them at Christmas in a big photograph with their families, and it helps. It's kept me from homicide.

MUSICIAN: You've called this record the end of a trilogy, which suggests you're preparing to move in another direction.

WAITS: I don't know, maybe the next one will be a little more... hermaphroditic. But I'm a real procrastinator. I wait till something is impossible to ignore before I act on it.

MUSICIAN: That's surprising, there's enough songs on your last three albums to make about six normal-sized records.

WAITS: More for your entertainment dollar! That's what we say down at Waits & Associates. Go ahead, shop around, compare our prices. Come back on down.

MUSICIAN: Well, you have written a lot of songs here.

WAITS: And none of them will be used for beer commercials. It's amazing, when I look at these artists. I find it unbelievable that they finally broke into the fascinating and lucrative world of advertising after years on the road, making albums and living in crummy apartments; finally advertising opened up and gave them a chance for what they really wanted to do, which was salute and support a major American product, and have that name blinking over their head as they sing. I think it's wonderful what advertising has done, giving them these opportunities to be spokesmen for Chevrolet, Pepsi, etc.

MUSICIAN: Do you ever get approached by major advertisers?

WAITS: I get it all the time, and they offer people a whole lot of money. Unfortunately I don't want to get on the bandwagon. You know, when a guy is singing to me about toilet paper(3) - you may need the money but, I mean, rob a 7-11! Do something with dignity and save us all the trouble of peeing on your grave. I don't want to rail at length here, but it's like a fistula for me. If you subscribe to your personal mythology, to the point where you do your own work, and then somebody puts decals over it, it no longer carries the same weight. I have been offered money and all that, and then there's the people that imitate me too. I really am against people who allow their music to be nothing more than a jingle for jeans(4) or Bud. But I say, "Good, okay, now I know who you are." 'Cause it's always money. There have been tours endorsed, encouraged and financed by Miller, and I say, "Why don't you just get an office at Miller? Start really workin' for the guy." I just hate it.

MUSICIAN: It's especially offensive if, as you say, you see music as something organic.

WAITS: The advertisers are banking on your credibility, but the problem is it's no longer yours. Videos did a lot of that because they created pictures and that style was immediately adopted, or aborted, by advertising. They didn't even wait for it to grow up. And it's funny, but they're banking on the fact that people won't really notice. So they should be exposed. They should be fined! [bangs his fist on the table] I hate all of the people that do it! All of you guys! You're sissies!

MUSICIAN: I think a lot of people notice, but the resistance isn't organized. Nike claims they only got thirty letters about using the Beatles to sell sneakers.

WAITS: I must admit when I was a kid I made a lot of mistakes in terms of my songs(5); a lot of people don't own their songs. Not your property. If John Lennon had any idea that someday Michael Jackson would be deciding the future of his material, if he could I think he'd come back from the grave and kick his ass, and kick it real good, in a way that we would enjoy. Now I have songs that belong to two guys named Cohen(5) from the South Bronx. Part of what I like about the last three albums is that they're mine. To that point I didn't own my copyrights. But to consciously sell them to get the down payment on a house, I think that's wrong. They should be embarrassed. And I rest my case.

MUSICIAN: When you began was there concern that your voice lacked the qualities of a classic singer?

WAITS: In terms of what was going on at the time? "Are you gonna fit in? Are you gonna be the only guy at the party with your shirt on inside out?" I was never embarrassed, but I'm liking it more now. Learning how to make it do different things.

MUSICIAN: I like your falsetto on "Temptation."

WAITS: Oh yes, a little Pagliacci.

MUSICIAN: It's true you sang several of the new tunes through a police bullhorn?

WAITS: I've tried to simulate that sound in a variety of ways - singing into trumpet mutes, jars, my hands, pipes, different environments. But the bullhorn put me in the driver's seat. There's so much you can do to manipulate the image, so much technology at your beck and call. But still you gotta make choices. A lot of this stuff is 24-track; I finally allowed that and joined the twentieth century, at least in that regard.

MUSICIAN: Certainly not in the sense of giving the music an aural sheen.

WAITS: I don't want the sheen. I don't know, I'm neurotic about it, and yet Prince is really state-of-the-art and he still kicks my ass. So it depends who's holding the rifle.

MUSICIAN: Prince has complained about not hearing enough "colors" on the radio, that too many talented people deliberately seek to emulate a formula instead of finding their own voice. Do you agree?

WAITS: To an extent. The business machinery has gotten so sophisticated, people want their head on his body. It's a melting pot, and the nutrition gets boiled out. Prince is rare, a rare exotic bird! There's only a few others. To be that popular and that uncompromising, it's like Superman walking through the wall. I don't think we can do it, you know. But this record goes into a lot of different musical worlds. "I'll Take New York" was a nightmare - Jerry Lewis going down on the Titanic.

MUSICIAN: I like the North African horn parts on "Hang On St. Christopher," which give it a vaguely menacing quality.

WAITS: [hums a snatch] That just happened in the studio... I think in music the intelligence is in the hands. The way your hands rub up along the ends of a table. You begin to go with your instincts. And it's only dangerous to the degree that you only let yourself discover the things that are right there. You'll be uncomfortable and so you'll keep returning to where your hands are comfortable. That's what happened to me on the piano. I rarely play the piano because I find I only play three or four things. I go right to F# and play "Auld Lang Syne." I can't teach them, so I make them do something else.

MUSICIAN: Are you more free on guitar?

WAITS: Not necessarily. I like picking up instruments I don't understand. And doing things that may sound foolish at first. It's like giving a blow torch to a monkey. That's what I'm trying to do. Always trying to break something, break something, break through to something.

MUSICIAN: You use a lot of "found" items in the music.

WAITS: That's a trap too. Though there's something in the fact of a studio with instruments you've spent thousands of dollars renting, to walk over to the bathroom and the sound of the lid coming down on the toilet is more appealing than that seven-thousand-dollar bass drum. And you use it. You have to be aware of that. And it makes you crazy. When the intervals and the textures begin to disturb you more than the newspaper, or your rocking chair or the comfort of your mattress, then I guess you're in for the long haul.

MUSICIAN: Well, you still have a few possibilities left.

WAITS: Which is fine if it hasn't been done. You have to feel it hasn't been done until you do it. Tape a bottle of Scotch to the tape recorder. Give a Telecaster to Lawrence Welk(6). We'd all like to hear what that's like. They're very conscious decisions. You have to believe it's unique to your experience.

MUSICIAN: I think it's encouraging that you're getting more successful as you explore these musical boundaries.

WAITS: What do you mean by success? My record sales have dropped off considerably in the United States. I do sell a lot of records in Europe. It's hard to gauge something you don't have real contact with. We have no real spiritual leadership, so we look to merchandising. The most deprived, underprivileged neighborhoods in the world understand business. Guns, ammo, narcotics... But yes, SALES HAVE DROPPED OFF CONSIDERABLY IN THE LAST FEW YEARS... and I want to talk to somebody about it. I used to play Iowa. I haven't been to Iowa in some time.

MUSICIAN: Have you considered moving there?

WAITS: Ah, I could never live in Iowa. No offense to people who do. When I tour it's like, people want to see you in one way, and they want to get familiar with you. When I find someone I like, I don't buy every record they ever made. Rarely. But I'm like, "Oh yeah. I know that guy." We all do that. And then it's - "Oh, you're still around, huh?" It's like birdwatching. "The oriole is back at the birdbath, no crows this year." What does that mean? We watch it like weather. We actually think that the media is like cloud formations. And we'll make judgments - "I heard he was up at the Betty Ford Center." And I like folk tales, and the way stories and jokes travel. But the media understands it as well. Fashion operates in that world. The top designers for the biggest companies go down into bad neighborhoods to find out how people are rolling their pants. It's all now, NOW. Which gets me railing again.

MUSICIAN: But there's still a funny parallel there with what you do, because even your description of "junkyard orchestration" implies the gathering of random elements-

WAITS: My personal version of that. The thing is, when you hit a vein, you make a breakthrough, there are a lot of people who want to go through that door. Whether you made it with a screwdriver or an M-16, there'll be a lot of traffic. So I don't tap into a national highway. I really think you have to be careful. Everybody looks at the country as this big girl they want to kiss. Like they're courting this big broad, you know? Gonna take the baby out, yeah, show her a good time. Does this sound silly? I'm just talking off the top of my head.

MUSICIAN: Is it upsetting that by taking chances you seem to lessen the likelihood of reaching a wider audience?

WAITS: Music is social, but I'm not making music to be accepted. I think everyone has to go out on their own journey.

MUSICIAN: Is it helpful to have developed a separate vocation as an actor?

WAITS: [takes mock offense} What, you don't think I can make a living just playing my music, is that what you're insinuating? But it helps with the groceries?

MUSICIAN: No, I mean does one complement the other? Your acting helps enlighten your music, or vice-versa?

WAITS: Like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. I don't know; you hope to see things. I think it's part of the same thing. Actors see what they do as conceptually [as musicians], they regard the same by-laws. I can't honestly say I'm accomplished as an actor. I have a lot of respect for those that are.

MUSICIAN: You just worked with Jack Nicholson in Ironweed-

WAITS: That was great for me. He's a badass. He lives in the ether, he walks like a spider. Got great taste. He knows about everything from beauty parlors to train guards. Hell kick your ass, he's a giant. He's got himself a place on the board of directors historically, and he does it with his feet. You see him and you know it's not like watching a wild horse. He knows what he's doing. He's like a centaur.

MUSICIAN: You appreciate people that can combine that animal instinct with intellectual control. Keith Richards seems like that.

WAITS: He is, he's the best. He's like a tree frog, an orangutan. When he plays he looks like he's been dangled from a wire that comes up through the back of his neck, and he can lean at a forty-five-degree angle and not fall over. You think he has special shoes. But maybe it's the music that's keeping him up.

MUSICIAN: Reading Ironweed, in the first scene when your character and Nicholson's are on your way to work in the cemetery, reminded me of your song "Cemetery Polka."

WAITS: Did it? Every time I buy a pair of shoes I get nervous. Wondering how long these shoes are going to be with me. Every time I see photographs of dead people, I always look at their shoes. It looks like they only got them a couple of weeks ago, they were the last pair [laughs], "All out of brown, all we have are black Oxford." But that "Cemetery Polka" was ah, discussing my family in a way that's difficult for me to be honest. The way we talk behind each other's backs: "You know what happened to Uncle Vernon." The kind of wickedness that nobody outside your family could say. That kind of stuff.

MUSICIAN: Do you ever feel your songs should be more personal?

WAITS: I don't like songs that are like some kind of psychiatry. I don't even want to know, in most cases, what the original idea was. Usually I hate pictures of the family and that kind of stuff. Sometimes it catches you in an odd moment you like. But with songs you have to make decisions about what it turns into, and I don't like it too close to what really happened. Occasionally truth is stranger than fiction, but not always.

MUSICIAN: Do you feel part of a fraternity with certain artists?

WAITS: You mean rate my fellow performers? I know the magazine is big on this.

MUSICIAN: Yeah, it's a tic.

WAITS: If you talk too much about people it kind of demystifies them, you know. And it's like watching things that are moving; you may like them today and not tomorrow. People who have careers are moving targets. Who would have known some guy you liked would go and do commercials for Honda? And then you're embarrassed to dig him, 'cause they tampered with their mythology. The guy was doing a beautiful tailspin, he went into a double flip with a camel-hair thing and then - right into the crapper. I like the Replacements(7), I like their stance. They're question marks. I saw them at the Variety Arts Center downtown; I liked their show. I particularly liked the insect ritual going on at the foot of the stage. There was this guy trying to climb up, and they kept throwing him back, like a carp. No, you can't get in the boat! It was like something out of Mondo Cane. [laughter] And it was really great to watch. And I liked the fact that one of the kids - Tommy? - had dropped out of high school. Being on the road with this band, the idea of all his schoolmates stuck there with the fucking history of Minnesota, and he's on a bus somewhere sipping out of a brandy bottle, going down the road of life.

MUSICIAN: Do you know why you became a musician?

WAITS: I don't know. I knew what I didn't want to do. I thought I'd try some of what was left over.

MUSICIAN: Were you from a musical family?

WAITS: Not like Liza Minelli, alright? Contrary to popular belief, we don't have the same mother. I took her out a couple of times: Nothing ever happened!

MUSICIAN: Were your folks encouraging?

WAITS: I think when children choose something other than a life of crime, most parents are encouraging. Music was always around when I was a kid, but there wasn't a lot of "encouragement"- which allowed me to carve my own niche. When you're young you're also very insecure, though. You don't know if you can lean on that window, if it'll break. It goes back to what I was saying about flying upside down by choice. There's a time when you don't understand, when you're not focused, not like the sun through a magnifying glass burning a hole in the paper. I used to do that every day when I was a kid. And when the glass broke I'd get another. It was no big deal. I didn't really know what I was doing when I started. I have a better idea now. In a way, I'd like to start now. A lot of great guys, only one third of them is visible, the rest is beneath the ground. Took them ten years just to break the surface. But when I started I thought, "Ah, I'd better get something going here." I still have nightmares about the stage where everything goes wrong. The piano catches fire. The lighting comes crashing to the stage, the curtain tears. The audience throws tomatoes and overripe fruit. They make their way to the front of the stage, and my shoes can't move. And I always play that in my head when I'm planning a tour. The nightmare that you will completely come unraveled.

MUSICIAN: You've suggested taking Frank's Wild Years on the road with a "Cuban Dream Orchestra." What does that mean?

WAITS: What will I take on the road? The thing is, in the studio everyone can change instruments, you have cross-pollination. On the road you have to just get up and do it. It makes me nervous. You know those things you play at a carnival, the little steamshovel that always misses the watch? I never get what I really want on the road. It's always vaudeville.

MUSICIAN: So you're more comfortable in a studio?

WAITS: Well, I don't want to do things in there that make it impossible to reproduce onstage. Basically I work with instruments that can be found in any pawn shop, so it's just nuance. I have a band that I trust. They're like having a staff of people that can rob a bank, or they can wear women's clothing if necessary. Be interior designers, or restaurant workers. They're everything. And that's different. I can't do this by myself. But I just hate the way most equipment and instruments look on a stage.

MUSICIAN: The way they look?

WAITS: The wires and all that. These necessary, utility items make me feel like I'm in an emergency ward. I want to take the Leslie bass pedals(8) and raise them up to a kitchen table so you can play them with your fists. Which is what we did in the studio on "Hang On St. Christopher. " I'm trying to put together the right way of seeing the music. I worry about these things. If I didn't, it would be easier.

MUSICIAN: Do you have any idea what motivates you?

WAITS: I've said for a long time I've been motivated by fear. But I don't really know. And if I ever knew what it was, I don't know if I'd want to tell Musician magazine, no offense. If I knew it would probably make me very nervous.

MUSICIAN: Maybe if you knew it wouldn't motivate you anymore.

WAITS: This is really getting metaphysical. Is this for Omni magazine? Yeah, I do believe in the mysteries of things, about myself and the things I see. I enjoy being puzzled and arriving at my own incorrect conclusions.

MUSICIAN: Any advice for younger musicians?

WAITS: Break windows, smoke cigars and stay up late. Tell 'em to do that, they'll find a little pot of gold.

Sidebar:

SWORDFISHMEGAPHONES

Tom Waits contends that most of what's played on his records can be found in a local pawn shop; locating some of them in a music store might prove more difficult. The current apple of his musical arsenal, for instance, is a police bullhorn, through which Waits fashioned many of the vocals you hear on Frank's Wild Years. Not just any horn, of course, but an MP5 Fanon transistorized megaphone (with public address loudspeaker). "It's made in Taiwan," Waits adds proudly.

Waits also plays a variety of keyboards, including a Brunello de Montelchino pump organ, a Farfisa organ and the famous Optigon, a keyboard made between 1968 and 1972 and marketed by Penney's stores. The Optigon plays pre-recorded sounds, which can be selected from its library; Tom particularly likes "Polynesian village" and "romantic strings." Not too surprisingly. Waits prefers "mostly tube stuff' to digital equipment.

Microphones of choice include a Ribbon ("Dave Garroway") and RCA high-impedance mikes; Waits usually sings through a Shure Green Bullet (used mostly by harmonica players). Also an Altec 21D vocal mike- "because Sinatra used it."

On guitar, Waits likes his Gretsch New Yorker "with old strings" played through an old Fender tweed basement amp. When recording, he says he uses a lot of heavy compression with room sound; to do that he'll sometimes push the track into the room through Auratone speakers, and then mike that. It's not his only technique, "but I don't want to give away all my secrets."

Notes:

(1) Springsteen's "Jersey Girl," the Eagles' "Ol' 55": Live 1975-1985. Bruce Springsteen, 1987. Sony Music/ Legacy Records/ On The Border. The Eagles, 1974. Elektra/ Asylum LP 1004 (re-released by Elektra Entertainment in 1990). Further reading: Discography - Covers

(2) In Genesis that man was made from clay: Genesis (chap. ii., 7): "And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground.". Further reading: The Genesis Site

(3) When a guy is singing to me about toilet paper: refers to Waits's old friend from the late 1970's Dr. John doing a commercial for toilet paper. "Dr. John was born Malcolm John Rebennack in New Orleans in 1940. He said he grew up on Bayou Road, in the neighborhood where Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton were born. He started playing piano when he was 6, studying with his mentor, Professor Longhair. His parents gave him guitar lessons with Fats Domino's guitarist, Walter "Papoose" Nelson. His father was a sound system repair man who sold rhythm and blues records on the side, so Dr. John said he got the first listen to anything he wanted. He spent most of his time in school writing songs, so he dropped out during his junior year in high school. His first album to gain critical acclaim was 1968's Gris-Gris (a Creole term for home-brew magic), which he said he recorded on Sonny and Cher's studio time. He created the "Dr. John the Night Tripper" stage persona in the 1960s. It is based on the legend of a 19th-century New Orleans hoodoo man, spiritualist and snake oil salesman. He used to have snake-handling dancers, flaming limbo sticks on stage as he appeared out of a cloud of smoke, dressed in glittery feathers and Mardi Gras beads. The bejeweled alligator skin he wore onstage and glitzy gris-gris charms are gone -- they burned in a studio storage fire a few years back... Dr. John sings the Popeye's jingle, and he has done commercials for cookies, toilet paper and dog food. (He just got a year's supply for his half-lab, half-bloodhound Lucy -- he calls her "loosely." "She ain't wrapped too tight in some ways," Dr. John said.)" (Source: "Dr. John doesn't want a cure for the blues", Augusta Chronicle by Wendy Grossman. September, 1998)

(4) To be nothing more than a jingle for jeans: This is before Herb Cohen, made a deal with the European branch of jeans producer Levi Strauss & Co. to use Screamin' Jay Hawkins's version of "Heartattack And Vine" for a TV-commercial (called "Procession", 1993). Further reading: Copyright

(5) I made a lot of mistakes in terms of my songs/ Two guys named Cohen: refering to Herb Cohen possesing and exploiting the rights to Waits's Asylum songs. Further reading: Copyright

(6) Lawrence Welk: host of an American musical TV series. The Lawrence Welk Show, was first seen on network TV as a summer replacement program in 1955. Although the critics were not impressed, the show went on to last 27 years. His format was simple: easy-listening music, what he referred to as "champagne music," and a "family" of wholesome musicians, singers, and dancers. Most of the regulars stayed with the show for years, but a few moved on--or who were told to move on by Mr. Welk. In 1959, for example, Welk fired Champagne Lady Alice Lon for "showing too much knee" on camera. After receiving thousands of protest letters for his actions, he attempted to have Alice return, but she refused. Welk himself was the target of endless jokes. His thick accent and stiff stage presence were often parodied. But viewers were delighted when he played the accordion or danced with one of the women in the audience. Fans also bought millions of his albums which contributed to the personal fortune he amassed, a fortune including a music recording and publishing empire and the Lawrence Welk Country Club Village. The final episode of The Lawrence Welk Show was produced in February 1982." (Source: "The Lawrence Welk Show", by Debra Lemieux. The Museum of Broadcast Communications � 2004 Copyright)

(7) I like the Replacements: Waits often expressed his appreciation for The Replacements. He contributed vocals to the track "Date To Church" w. The Replacements (I'll Be You (single), The Replacements, 1989. Sire (Sire 7-22992-B, Sire Australia MX-302453). Also released on "Just Say Mao" (Vol. 3 of Just Say Yes), various artists. July 11, 1989. Warner Brothers/ Sire Records (Sire 9 25947-2) and "All for Nothing, Nothing for All", The Replacements, 1997. Reprise (Reprise 9 46807-2). Further reading: TwinTone Records, Paul Westerberg homepage

(8) Leslie bass pedals: A Hammond organ is an electromagnetic instrument, with an inside consisting of tons of wires, cables and tubes. The sound from the organ is produced by small cogwheels which are rotating in front of magnetic coils. The tone produced are amplified and transformed into different soundings by so called drawbars, theoretically giving the organist 252 million different sound and tone combinations to choose from. Another important ingredient in the making of the Hammond sound, is the famous separated Leslie speaker cabinet. Inside the Leslie you'll find a speaker mounted on a rotating disc, and when the disc is in motion, a periodical sound change occurs and the pitch is sounding to be alternately higher and lower. The Leslie Rotating Speaker was named after its inventor, DonLeslie. First models began to appear around 1940. It is designed as a sound modification device, not a hi-fi speaker. The pairing of the Leslie Speaker with another device, for instance the famous Hammond B3 organ, constitutes a musical instrument. Here Waits only plays the bass pedals of a Hammond B3/ Leslie combination. Further reading: Instruments