|

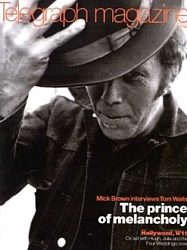

Title: Tom Waits, Hobo Sapiens Source: Telegraph Magazine, by Mick Brown. Photography by Neil Cooper Date: China Lights/Santa Rosa. April 11, 1999 Key words: Mule Variations, Fun, Napoleone's, Public image, Interviews, Commercials, Family, Songwriting Magazine front cover:1999. Photography by Niel Cooper(?) |

| Accompanying picture |

Tom Waits, Hobo Sapiens

The Career Of The Reclusive And eccentric Singer-Songwriter Tom Waits Has Always Been Couloured By His Uncompromising Vision Of American Life, Here, One Of The Greatest Storytellers Of His Generation Shoots The Breeze With Mick Brown, Photographs By Neil Cooper

Tom Waits first made his name by singing songs about that area of town marked out by the pawnbroker, the tattoo-parlour and the Greyhound bus station. These were wonderful stories - funny, sad and wise - in which hookers were saints and skid-row bums were lovingly depicted as 'little boys', and which led Francis Ford Coppola to describe him as 'the prince of melancholy'.

Waits, who has just made his first album in six years, describes his songs as 'little movies for the ears', and there is one song in particular on the new album which is more explicitly cinematic than most. What's He Building? is a mystery story of the suburbs. Against a background of scratchy, Twilight Zone sound effects, Waits assumes the role of a nosy neighbour, narrating a dossier of the strange goings-on next door:

'He has subscriptions to all those magazines. He never waves when he goes by. He's hiding something from the rest of us. He has no dog and he has no friends and his lawn is dying, and what about all those packages he sends? Now what's that sound from under the door? He's pounding nails into a hardwood floor, and I swear to God I heard someone moan low and I keep seeing the blue light of a TV show. What's he building in there?'

Superficially a parable of suburban manners, it can also be read as a satire on the media's invasion of privacy. 'It's about thinking we have a right to know,' growls Waits. 'Y'know, he drives a blue Mazda and doesn't get home until three in the morning. He was karate-chopping his own shrubbery last night - in his underwear. So we put all those things together and we make up a story about someone that bears no resemblance to the truth, and then we make it a serial. And that's what happens with the media. We love looking at each other through keyholes. They ought to make keyhole-glasses, they'd sell a million of 'em, because that's how we prefer looking at each other, down on our knees in front of a keyhole.'

What's he building in there? It's a question that could reasonably be asked of Tom Waits himself.

Ever since he started making records in the Seventies, Waits has been pounding the hardwood floor and karate-chopping the shrubbery to produce the most singular and unusual body of work to be found anywhere in popular music, Is he a musician? A poet? A storyteller? An actor playing a part.

Or a part playing the actor? Time has suggested that Waits is all of these things and more. Over the past 25 years, he has recorded 15 albums; he has written operettas and film music, and as a screen actor he has worked with directors as various as Coppola, Jim Jarmusch and Robert Altman.

What has made his work all the more compelling is the character of Waits himself. With his boho threads and graveyard pallor, he arrived on the music scene looking, and behaving, like a man who had stepped out of a story by Charles Bukowski - an inebriated barfly, down in the gutter but looking up at the stars, with a hatful of sad stories about life's losers and a withering put-down for anyone who tried to get behind the veneer.

Waits has always been a man who would rather tell an entertaining lie than a prosaic truth, who greets any direct question, particularly one pertaining to his personal life, with all the enthusiasm of a dying man who spies an undertaker brandishing a tape-measure at the foot of his bed.

I remember meeting Waits in 1976(1) , on his first visit to Britain, and making the mistake of asking him for his definition of fun. He examined the word as if he'd scraped it off the bottom of his shoe.

'I don't have fun. Actually, I had fun once, in 1962. I drank a whole bottle of Robitussin cough-medicine and went in the back of 1961 powder-blue Lincoln Continental to a James Brown concert with some Mexican friends of mine. I haven't had fun since. It's just not a word I like. It's like Volkswagens or bell-bottoms, or patchouli oil or bean sprouts. It rubs me up the wrong way. I might go out and have an educational and entertaining evening, but I don't have fun.'

That interview, inevitably, took place in a pub. Waits was wearing a thrift-shop suit, blackened with neglect, and apparently hadn't caught sight of a razor in days. It was lunchtime, but he already seemed somewhat the worse for wear. He had come to London to perform at Ronnie Scott's club(2) . For three nights he sat at the piano, peering out at the empty seats through a haze of smoke from the cigarette cemented to his bottom lip, performing his songs of wry and melancholic beauty. On the fourth night they threw him out. 'I think it was my clothes,' Waits says now. 'Every time I tried to go into a restaurant, people would chase me out. I couldn't even get a sandwich.'

Such is the mythology surrounding Waits that there is an Internet site - The Tom Waits Memorial Tour of Joints - dedicated to chronicling the various bars and restaurants across America where Waits either has or 'would' spend his time. These are places whose very names suggest low life and tall stories: the Hi-Boy in Washington DC; Rose's Night Life, 'just north of the South Platte River' in Denver, Colorado, and the Uranium Cafe in Grants, New Mexico.

The China Lights in Santa Rosa, northern California can now be officially added to the list; a quiet, neighbourly and agreeably cheap Chinese diner beside the railway tracks.

Tom Waits has only ever given interviews looking down the barrel of a gun, and in recent years he has avoided the media altogether. It is only the release of his new album, Mule Variations, that has persuaded him to drive the 20 or so miles from his home in the heart of the wine-growing district - where he lives with his wife, Kathleen, and their three children - to take up temporary residency in a booth at the back of the restaurant, behind a plate of steaming chow-mein and a bottomless pot of Chinese tea.

His beaten-up pick-up truck is parked outside, laden down with bags of water-softener for his swimming-pool. This is more incongruous than it sounds: Waits is a man whose milieu has always seemed strictly nocturnal; he is not the kind of person, you would think, who would even recognise a swimming-pool, let alone maintain one.

He is wearing heavy-duty jeans and a denim jacket, motor-cycle boots and a trilby hat. His face is weatherbeaten and lined: the crinkled eyes and the merest suggestion of a goatee shadowing his bottom lip lend him a curiously oriental aspect. There was a period in his life when Waits's voice was most usually described as having been marinated in nicotine and cheap booze. He gave up smoking years ago and nowadays drinks only in moderation, but there is still something alanningly tubercular in his rough, grumbling growl.

'I'll tell you some things I've been thinking about lately.' He puts down his cup of tea, reaches into his bag and pulls out a notebook, which he scrutinises in a parody of academic seriousness. 'Did you know that cockroaches can live for several weeks with their heads cut of!'?'

The delivery is perfectly deadpan. 'Here's something else:

People that observe ants closely say that they actually stretch when they wake up in the morning, and they yawn. Now a scorpion...'

A scorpion?

'If you put a minute amount of liquor on a scorpion, it will go mad and sting itself until it's dead. These are things I find interesting, to keep myself from going crazy. I have a radio show called "Strange and Unusual Facts", and these are some of the things we talk about every week. We broadcast from a little town called Miner's Prayer(3) , Nevada. It's a small station, a very limited range, but a lot of people listen in. They've moved there because of the show - that's what we've found.'

Does Tom Waits really host a radio show in the Nevada desert? You might as well ask whether he was really born 'in the back seat of a yellow cab in the Murphy Hospital parking-lot at a very young age' - the answer he would traditionally give to inquiries about his birthplace. The reference books say that he was born in 1949, in Pomona, California. His parents were schoolteachers who divorced when Waits was young. By the age of 14 he was working as a short-order cook in a pizza parlour, Napoleon's, in a small Californian town called National City - 'a stone's throw away,' he recalls, 'from Iwo Jima Eddie's tattoo-parlour and across the street from Club 29, Sorenson's Triumph motorcycle shop and Phil's Porno.'

'I thought I was gonna be a cook,' he says. 'That's about as far as I could see. But what also happened was that I was mystified by the jukebox, and the physics of how you get into the wire and come out of the jukebox. That's where that came from. I'd listen to Ray Charles singing Crying Time and I Can't Stop Loving You, and I'd think, goddamn, that's something.'

After dropping out of high school, Waits worked in a variety of jobs - 'a jack-off of all trades' - eventually finding work as a nightclub doorman, while living out of the back of his car. It was here that he started writing down conversations overheard at the bar, 'and realising they had music in them'.

By then, he had developed a romantic fascination with the boho mythology enshrined in the work of such writers as Bukowski, the poet Delmore Schwartz, who died in a run-down hotel for transients in 1966, and, above all, Jack Kerouac. Waits discovered On the Road when he was 18 years of age. 'It spoke to me,' he says simply. 'I couldn't believe that somebody'd be making words that felt like music, that didn't have any music in it, but had music all over it.

'I was the bouncer in this nightclub - place must have been really hurting if they had me as their bouncer; everybody got in - and I'd bring my books and my coffee and my cigarettes and put my feet up, and I'd read my Kerouac, and watch the cars go by, and I just felt like I was on fire and I had a reason to live. Because he put some meaning on the most ordinary things. Sitting there, my own ordinary life was just lifted out of that and I was all dusted with something sparkling.'

References to Kerouac have sounded intermittently in his work ever since: he once recorded a song, Jack 'n' Neal, celebrating the friendship of Kerouac and Neal Cassady, and he has recently recorded a song called On the Road(4) for a tribute album, which incorporates snatches of the writer scat-singing at a party. But what he shared most with Kerouac was a sympathy for the outsider. Like Kerouac's books. Waits's songs turned loneliness into an adventure, being dead-beat into a state of grace.

Waits began his recording career in the early Seventies, after being discovered singing at the Troubadour club in Los Angeles by a man named Herb Cohen, who managed Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart. (Waits would later recall that he had met Cohen outside the club: 'He was exposing himself. Actually, it was so cold that he was just describing himself.')

His first albums were peopled with America's flotsam and jetsam: barflies and losers; the stripper who makes you 'harder than Chinese algebra'; the small-town studs who boast of getting 'more ass than a toilet seat'; low-rent hoodlums and sad-eyed peroxide waitresses promising love over easy ('They all cooked dinner on my stove').

These were songs that had a way of sidling up on you like a stranger in a bar with a story to tell ('The dreams aren't broken down here,' Waits croaked, 'they're just walking with a limp'), romantic celebrations of the bare and enduring fact of existence under even the most straitened of circumstances. The characters in his songs may have lost their shirts and their temper, but never their human dignity.

Working on the principle that to write about something you must live it, Waits cultivated the habits as well as the appearance of a skid-row derelict. He dressed cheaply and made a point when on the road of staying only in the most insalubrious places. His 'home' was a room in the notorious Tropicana motel in West Hollywood(5) - better known as the place where the soul singer Sam Cooke was shot dead. There was a piano where the refrigerator should have been, and the gas-stove was 'just a big cigarette lighter'.

For a long time, Waits admits, he was in danger of being overtaken by the low life he wrote about. He drank too much. He made bad friends. 'I wanted to experience what it was like to be on the road the way I imagined it would be for all the old-timers that I loved, so I would stay in these down-joints because I was absorbing all the atmosphere in those places; the ghosts in the room.

'You want to be where the stories grow, and you think if you live in those places they'll come up through the sidewalks and out of the cracks in the wall - and they do. But you have to be very clear about who you are and who it is you're projecting, and there was a time when I was very unclear about who I was. I became a caricature of myself.'

Whatever the moment of truth, how far he fell and how he stopped falling, Waits is reluctant to say. Interviews 'aren't supposed to be depositions', he says, 'and they're not therapy I'm not entirely sure how I want to characterise what I feel about all that, because I'm still trying to figure it out.

'But I do know you have to protect yourself. Y'see, most of us expect artists to do irresponsible things, to be out of control. Somehow we believe that if you're way down there, you're going to bring something back up for us, and we won't have to make the trip. Go to hell with gasoline drawers on and bring me back some chicken chow-mein while you're at it. This is part of the tradition of artists; the problem with that is that you have people who will write you a ticket to go to hell; they support your bad habits. So you got to be careful.'

He pauses, reflecting on this. 'The fact is that everybody who starts doing this to a certain extent develops some kind of a persona or image in order to survive. Otherwise it's very dangerous to go out there. It's much safer to approach this with some kind of persona, because if it's not a ventriloquist act, if it's just you, then it's really scary.

'The whole thing's an act. Nobody would really show you who they are - nobody would ever dare to do that, and if they do, they change their mind after a while because it gets to a point where you don't know what's true any more. The dice is throwing the man, instead of the man throwing the dice.'

It was the film director Francis Ford Coppola who was to prove the catalyst in Waits's life when, in 1979, he asked Waits to write a suite of songs as the soundtrack for his Las Vegas romance One from the Heart. Waits spent 12 months on the project, turning up each day at his office at Coppola's Zoetrope studios. He fell in love with, and married, Kathleen Brennan, a script editor on the film. And the commission led to Coppola's casting Waits in his first film role, in Rumble Fish. Since then he has appeared in two more Coppola films and had starring roles in Jim Jarmusch's Down by Law and Robert Altman's Short Cuts. He has recently completed a new film called Mystery Men(7) , with Geoffrey Rush and Eddie Izzard. 'It's about low-rent super heroes; the guys who never get to save the day or win the girl or any of that,' says Waits, who plays a weapons designer.

He once described the transition from music to acting as 'like going from bootlegging to watch repair'. 'I usually play small parts,' he says, 'which is just as well. But a small part in a film is rather wasteful. You go and you sit and you sit... The acting is free. You charge them for the waiting. That's the way I see it. I like acting, but it's not something I consider myself an expert at. When I'm recording music I can be uninhibited and I can sing a song seven different ways. There are actors that can do that with a director: the first take is like some kind of rant; the next take is a prayer; the next take is like some old black man. They can go through all these different moves. I'm not able to do that as an actor.

This is true. Whether cast as a small-time hood in Rumble Fish or a truculent limo driver in Short Cuts, Waits's characters always seem to be less roles that he is playing than different ways of playing himself.

'You could say the same thing of Gary Cooper and Cary Grant,' says Robert Altman. 'Tom is unique - completely his own person. He's bent, but in the right way. It's a good bend.'

Altman describes himself as Waits's greatest fan: 'I just love whatever he does. If I feel the need to cry, which I find it hard to do nowadays, I only have to put on one of his albums.' And the feeling is mutual. Waits describes Altman as 'a good sheriff in a bad town'.

'Well, that's because Tom spends all his life in bad towns,' Altman jokes.

Waits is the first to admit that his work has never conformed to the 'cover-the-earth' theory of merchandising, 'like shoes, hair-tonic or sunglasses'. For years, his records were a well-kept secret. It was only with the release of Swordfishtrombones in 1983 that he began to attract a wider audience. By then Waits had all but abandoned the fake cocktail-jazz aesthetic of his early work. He incorporated wheezing accordions and pipe organs, vocals sung through a police bullhorn, percussion that sounded like something that had come up from the swamp, rattling its bones and chains - a process he once described as 'taking things that don't necessarily belong together and forcing them to get stuck in the same elevator.

It's likely that he has made more money from other people's recordings of his songs - notably the Eagles' Ol' 55, Rod Stewart's versions of Downtown Train and Tom Traubert's Blues, and Bruce Springsteen's Jersey Girl - than he has made from all of his own albums put together. (Frank Sinatra's greatest mistake towards the end of his career was to ignore the advice of a producer who suggested he should record a collection of Waits's ballads.)

Probably the largest pay-cheque of his career came from a recent law-suit against an American crisp company, Frito-Lay(8) , which used a Waits 'soundalike' in an advertisement without his permission. Waits sued, winning more than $3 million in damages. 'I think your music is a gift, and I don't do commercials,' he says. 'There are people that do that, but I'm not one of them and I don't want people to think I am one of them, hawking cigarettes or potato chips.'

He has always been a man who works at his own pace, pursuing the projects he wants to pursue, making records when he, not the record company, wants. The pace has sometimes been frantic. In the 10 years between 1983 and 1993 he made seven albums, produced three stage plays (Frank's Wild Years, Alice and The Black Rider - the last two with the avant-garde playwright and director Robert Wilson), acted in a handful of films and contributed music to several more. But Mule Variations follows a six-year period in which Waits has been all but silent.

'I just thought I'd let things stack up for a little while. Do other things,' he says, dismissing the subject with a shrug of his shoulders. He moved to northern California from Los Angeles and concentrated on bringing up his family. 'You take a break and you get a new perspective, that's all. But I was tired of the old songs and needed some new ones. It's not like I couldn't record any time I wanted to. It's not like moving from Chicago to Marrakesh and not having the money to get home.

'I've got a tape-recorder that I carry round in my pocket; I record in the car, play it back; you bang out a rhythm on a chest of drawers with your fist in a motel room, record that. So in a sense I'm always recording things. It's like people that draw. Sometimes when I'm trying to get the kids to be quiet so I can think, I say, what do you like? When you're going to draw, do you like to start out with a piece of paper that's already scribbled on and find a little place down the bottom to do your drawing? Or do you like to get a nice clean, white sheet of paper? Which do you prefer? "Oh I want a clean, white sheet of paper." OK, well right now I can't hear; I'm trying to make up some. I need to have the auditory equivalent of a clean, white sheet of paper.' He shrugs. 'But they just carry on, throw things at me...

'They call me the preacher at home. Uh-oh, here he comes... the preacher. I yell and holler a lot. I rant.'

A disciplinarian, then?

Waits arches an eyebrow. 'Actually, I was raised a Methodist.'

Mule Variations sounds like a reconciliation of all the various musical styles that Waits has explored over the years, as if the songs have been hammered together from the skin and bones of American myth: scratchy Delta blues, Sixties R&B, vaudeville rants and Salvation Army band hymns.

The cast of urban picaroons who peopled Waits's early songs have largely vanished over the years (he has long been, in his own phrase, 'hanging off a different lamp-post'). Mule Variations is an American gothic exploration of rural primitives, freak-show exhibits and back-porch romantics, leavened with a handful of heartbreaking love songs which leave you feeling, as Waits puts it, 'like one eye is laughing and the other eye is tearing up'.

He pauses, fork poised over his Chinese meal. 'Do you know how many teardrops it takes to fill up a teaspoon? A hundred and twenty, actually. I tested it. I was very sad and I thought, I'm going to make some use of it, so I held a spoon at my cheek and I cried. This is my science project for the year.'

Songwriting, says Waits, is like 'birdwatching', or 'looking for insects. If you don't know what you're doing you'll spend all day and find nothing. Same things with songs. You've got to sneak up on them.'

And there's a particular recipe for making an album. 'You write two songs, you put 'em in a room and they have kids. Songs travel along the same line that jokes and stories do. They get written down, forgotten and resurrected. You tear the wings off them for a while and they grow new ones. Songs are kind of like your memory of something, your homeland, or what you had for dinner last night; something for your kids. We all do it naturally, and kids do it better than any of us. So in a sense, it's kind of like children's work.'

Since his marriage, he has co-written most of his songs with his wife, a process of collaboration which he likens, with characteristic quirkiness to, 'two people making dinner or carrying a piano or painting a fence. You work out your rhythm'. Kathleen, he says, 'doesn't like the limelight', but she has been an 'incandescent presence' in his life since the day they met. One of his most poignant songs, Johnsburg, Illinois, is a tribute to her:

'She's my only true love, she's all I think of look here in my wallet, that's her. She grew up on a farm there, there's a place on my arm, where I've written her name next to mine. You see I just can't live without her, and I'm her only boy and she grew up outside McHenry in Johnsburg, Illinois.'

Nobody writes love songs like Tom Waits, but he is uneasy talking about such things. He shifts in his seat, rubs his chin and says that his life is private and he likes to keep it that way. Waits doesn't want anyone looking at him through keyhole glasses.

He's tapping his fingers on the table. He's draining the last of his Chinese tea. He's turning the pages of his little notebook. 'Did you know,' he asks, 'that there's a town in Chile called Colamada where it has never rained. Never.' He pauses. 'They don't talk about a little rain. They don't talk about we'd like to have some more rain, or we're hoping for a little more rain. They've just given up the whole topic.'

He turns the pages.

'Here's another one. In Viking times, it was humans who were sacrificed on the prow of a ship, and of course from there it went to a bottle of wine. But the first time it was human beings. They'd volunteer. It was a short line - that real short line off to the right, just on the other side of the wharf, just two or three people. Depressed people.'

He scrutinises me suspiciously. 'You realise that all of this is on tonight's show. I'm trusting you're going to keep this between the two of us. And this is the lead story: Thomas Edison was deaf from the age of 12.'

There is no radio show, of course. But Tom Waits has always been a terrific act.

Notes:

(1) I remember meeting Waits in 1976: unknown/ unidentified interview

(2) Ronnie Scott's club:Ronnie Scott's Club, Soho/ London. May 31 - Jun. 12, 1976. Further reading: Performances

(3) Miner's Prayer: as mentioned in "What's He Building?" (Mule Variations, 1999): "I heard he has an ex-wife in some place called Mayors Income, Tennessee And he used to have a consulting business in Indonesia." Tom Waits (1999): "I got kind of a Unabomber image. We seem to be living in a time when the guy next door may be building a fertilizer bomb in his basement. Guess it's the rat theory: There's too many of us, and we're going crazy because of the proliferation of the human manifes ation. You go down the freeway, and all of a sudden there are 350,000 new homes where there used to be wilderness. They all have to go to the bathroom somewhere, they all want toys for their kids, they all want eggs and bacon and a nice little car and a place to vacation. When the rats get too plentiful, they turn on each other. Q: In the song you mention a town called Mayors Income, Tenn. TW: Came to me in a dream. Two towns. The other one, same dream, Miner's Prayer, W.V." ("The Man Who Howled Wolf ". Magnet: Jonathan Valania. June/July, 1999)

(4) On the Road: Jack Kerouac Reads "On the Road". Various artists. September 14, 1999 Label: Ryko. (Rykodisc 10474). TW contribution: guitar, percussion and vocals on "On The Road" (first release). Re-released on Orphans, 2006.

(6) A room in the notorious Tropicana motel in West Hollywood: Further reading: Tropicana Motel.

(7) Mystery Men: Mystery Men (1999) Movie directed by Kinka Usher. TW: actor. Plays weapons designer Dr. A. Heller. Further reading: Filmography

(8) Frito-Lay: further reading: Waits vs. Frito Lay