|

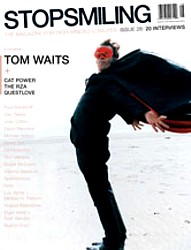

Title: Tom Waits Call And Response Source: Stop Smiling magazine No. 28 (USA). October 27, 2006. Telephone interview by Katherine Turman. Photography by Danny Clinch Date: Published October 27, 2006 Keywords: Orphans, touring, Theremin, Alice, Road to Peace, Bukowski, Internet, Frank Stanford, Richard Waters, acting Magazine front cover: Photography by Anton Corbijn (ca. 2002) |

Tom Waits Call And Response

Tom Waits sums up the fierce fascination fans have for all things Waitsian: "If you spill something, they want it." That's probably because even Waits's detritus is cooler than other artists' best efforts. And it's part of the raison d'�tre for his three-CD assemblage, Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers and Bastards, a career-spanning effort released by Anti- in November. A read between the lines of Bastards helps illuminate what makes Waits tick. In "Children's Story," he recites, in his world-weary rasp, "Once upon a time there was a poor child with no father and no mother / and everything was dead / And no one was left in the whole world / Everything was dead / The moon was a piece of rotten wood / The earth was an overturned piss-pot / And he was all alone." Waits ends the narration with a throaty chuckle. Deadpan, dark, but possessed of a wicked humor, Waits's arcane appeal incites in journalists a frenzy to invent new adjectives to capture and describe the nearly 40-year, multifaceted career and life of Thomas Alan Waits.

Even when Waits claims he's telling the truth, he may not be. He's a master yarn-spinner, a teller of tales tall and small. And though much is made of his persona, it seems the persona and the man have become one. But facts are facts: Waits was born on December 7, 1949 in Pomona, California, grew up near San Diego, and in 1971, signed to Asylum Records. Nineteen records followed from 1973 to 2004 on various labels, garnering, along the way, Grammy Awards, Academy Award nominations, film roles, a wife/collaborator in Kathleen Brennan, three children, and the adoration of a large and very rabid cult of cultural dissidents who elevated Waits to living icon status. As a folk hero, Waits's name is part of the pantheon of boho coolness populated by such contemporaries, and collaborators, as William S. Burroughs, Robert Wilson, Charles Bukowski and Jim Jarmusch.

If Tom Waits is impossible to categorize, he is certainly easy to like. When he's relating a story or singing - as opposed to merely answering a question - his voice gets even more resonant, more dramatic, wrapping a deceptively quixotic cocoon around the listener. He uses music biz terms like "added value" with a deadpan irony and understated emphasis, waxes ecstatic on strange and unusual facts about insects, and, as records from Swordfishtrombones to Frank's Wild Years attest, creates one-of-a-kind aural soundscapes that open a gargoyle-guarded gateway into an alternate universe. For these reasons and many more, Tom Waits is rightfully revered - and sometimes feared.

Calling from his home in rural Sonoma County, California, Waits was by turns shy, thoughtful, uncomfortable, teasing, amusing, endearing and just plain cool. He's the kind of guy you'd want to spend a late afternoon with in the gloomy half-light of a near-empty bar - with plenty of quarters for Waits to control the jukebox and conversation. But we happily settled for an early evening on the phone.

Stop Smiling: What made you decide to tour again?(1)

Tom Waits: I don't know what made me go out. We played a lot of "villes." I worked with a guitar player, Duke Robillard, who started a group called Roomful of Blues and the Fabulous Thunderbirds. He is a great blues guitar player. My son played drums. Then there's Larry Taylor, who has been with me for years, and who used to play with Canned Heat and Jerry Lee Lewis - he's played with everybody. Then on keyboards was Bent Clausen. I really wanted to find out if I like doing this. I wasn't really going out to make money. I've been doing it for a long time, and it's usually a lot of headaches, and the physics of most of the auditoriums is maddening from night to night. It's what everybody deals with. It kinda rattles me, and I usually end up a nervous wreck by the end of it. So I wanted to see if I could go out and actually enjoy playing. That was the whole objective of it. And I did.

SS: Would your feelings about playing qualify as stage fright?

TW: I don't know if it's stage fright. I'm always afraid things will go wrong. Plus, when you're taking this whole thing and you're moving it all around the country, it's always awkward. It's like, for me, moving somebody who has been in an accident, you know. "Don't move me, don't move me," that's the first thing the show says to me at the end of rehearsal. "Whatever you do, don't move me, I like it here."

SS: Maybe the country singers in Branson, Missouri who have their own theaters have the right idea.

TW: I've thought of that Branson deal. I've discussed that with other artists. Just the idea that you don't go on the road, they go on the road and come to you. Makes perfect sense to me. Getting out in front of all those people, after a while, if you're well prepared, it's fun. I'm not always well prepared. But this time I was, so I think that was a big part of it.

SS: Like you, I'm a native Californian. Do you draw inspiration from other places, or do you prefer home?

TW: I like going to guitar shops, pawnshops and salvage yards. I really like to go to hardware stores to see what they got out there, especially in Europe. I bought a two-by-four guitar in Cleveland. Everybody has a two-by-four lying around his or her yard. Send me a two-by-four and I'll make a guitar out of it. You don't see a lot when you're on the road, needless to say. You see the gig and the town on the way in and the town on the way out, but there's something sort of exciting about that at the same time - the stealth. You come in and sting 'em and go. That's what I call it. It sounds like a rockabilly title.

SS: Wasn't Asheville, North Carolina the home of the inventor of the Moog synthesizer?

TW: I don't know. Bob Moog(2) started making Theremins toward the end. Interesting man. My first experience with a Theremin was this gal Lydia(3), the granddaughter of Leon Theremin, who was living in Russia. We were in Hamburg doing Alice, this Robert Wilson thing. So we wanted a Theremin player, and someone said, "I know Lydia," and she came in and she looked like a little Russian doll, a traditional Russian sweater, and her Theremin looked like a hotplate. And inside, all the connections were held together with cut-up little pieces of beer cans that she twisted around the wires to hold the connections together. And the aerial was literally a car aerial from like a Volkswagen. And when she played, she sounded like [violinist] Jascha Heifetz.

SS: That brings us to these three CDs that I've been trying to absorb. Twenty years ago, all 54 of these songs would have been on cassette tapes.

TW: Oh, yeah. It would have been a mess. It's kind of overwhelming. Mainly, I was afraid I was going to lose all this stuff because I don't really keep good records. I don't have a big vault or a real organized room with all my stuff. I don't know. Maybe like you, I imagine, when I want something, I can't find it. And when I don't need it anymore, I find it. So I wanted to get this out. A lot of the stuff I bought from a guy in Moscow who had this stuff on a CD that he'd collected. It was weird: black market stuff from a guy in Russia. Some of it I never had the original or the DAT or the multi-track or even the half-inch. I just did it and then, you know, sting 'em and go. I'm starting to get more archival as I get older. "Oh, we better hang on to this, honey. We'll need this in our old age. We'll use it as a coffee table."

SS: When you were a kid, what kind of stories were read to you? Nothing about the world being an "upside-down piss pot"?

TW: An "overturned piss pot." I added that line. [Recites] "He is there to this day, all alone." Most children's stories have a dark element. There's the two brothers: One was kinda slow in the head, not very ambitious, and the other one left home early and got lost. They're always sad or frightening. Most of them are cautionary tales. When my kids were young, I would make stories up and say, "Give me the elements, what do you want in there? Okay, a tree, a polar bear and a typewriter. All right." That's how we usually start. Stories kind of tell themselves, especially when you're searching for the next chapter. It's kind of a real condensed version of what you do when you're really writing. When you're writing for kids, you have to come up with stuff on the spot.

SS: On Real Gone, you had "Day After Tomorrow." On the new CDs, there's the song "Road to Peace"(4) with the underlying political message. Where did the song's message come from?

TW: The New York Times. When you read the paper every day, it's hard to avoid that seeping into your consciousness. That was written not long ago. A lot of these were recorded within the last year. It's new stuff. I don't want to go into the origin of everything, but for me, they're from questionable sources. I didn't put any liner notes in because I didn't want to overexplain it. That one is a Bukowski poem, "Nirvana," and that "Pontiac" - that's my father-in-law's. If you go down to the market with him, you'll get that speech. Different every time. More cars, different cars, if he sees a Lincoln or a Hudson or an Impala, it gets him going.

SS: You mentioned Bukowski - have you seen the film adaptation of Factotum?

TW: No. I'm glad his stories are getting turned into movies. I'm a big Bukowski fan. What you really want to do is be valid and vital and in some way, here and after you're gone: to still remain a presence and influence and still be able to sprout and bloom and bear fruit. I guess that's what everybody wants.

SS: You covered the Daniel Johnston song "King Kong." Is that because you like the song, or Johnston himself?

TW: Well, Jim Jarmusch played me his version of "King Kong," and I tried to stay as true to that as I could. If you hear the original, you'll see what I mean. I got all his records. I thought I'd really discovered this: it's real outsider art. The interesting thing about outsider art is that it's such big business. These outsider artists are creating false biographies for themselves(5), saying they're victims of mental illness and child abuse, and they grew up poor in the South and they're creating these false backgrounds. You aren't really qualified as an outsider unless you've had no formal art education, so you have to prove that you have no art education at all. It's an interesting turn of the tables.

SS: Are you an Internet person?

TW: No. I'm not. I'm pretty backward. You can spend $400,000 on a painting that was done on the back of a cereal box with a Bic pen, which is an interesting place

to be at with the economy what it is now.

SS: In terms of recording technology -- is there anything you need nowadays to make the records you want to make, or is a two-by-four guitar enough for you?

TW: It seems you can create digitally -- you can re-create everything that was once done in analog. As soon as vinyl left, someone put pops and cracks over a song. I guess, culturally, we're always burying something and digging it up, burying it in order to dig it up. They do the same thing with hairdos and shoes and furniture. It's what we do. As far as the sound goes, most of the people I know are always looking for some very obscure apparatus that will give them some unusual sound source that they can use in the studio. Then someone says, "There's this thing called Amp Farm." It's a farm, and you hit the thing and 700,000 sounds come up, and you can pick from there. There's no reason to have 700,000 amplifiers anymore.

SS: Which way do you prefer?

TW: I'd rather have the devices, but you roll with it. I'm not an audiophile by any stretch of the imagination.

SS: So when CDs came about, did you think they were a passing phase?

TW: I figure it was like the bagel. They were designed to be carried in your pocket. And the outer surface was hard and leathery, so that the bread would be protected inside. It's just as big as your hand and fits right in your pocket. CDs are the same way; there's more room on the shelf. I have pockets that CDs fit in, and I appreciate that sometimes.

SS: Even with 50-something songs on these CDs, you have managed to find room for two hidden tracks.

TW: It's the little prize in the cereal box. If you dig to the bottom, you'll get the plastic rod and reel. It's an added value. I played the records for somebody and they said, "I've never heard any of these things." I said, Oh, good.

SS: One thing that struck me is that you don't have casual fans.

TW: Damn! It's supply and demand. Stay away and they get hungry. When they're hungry, they eat more. They eat better. That's always been my theory. I'm being

silly.

SS: I need to be across a table from you so I can see when your eyebrow is going up.

TW: I roll them.

SS: If you were a technology guy, we'd have videophones.

TW: Crime has them. Somewhere, someone is doing something with it that you can only imagine. Crime is way ahead of us. As a casual device, it doesn't have much

of a future, but it's probably great for prostitution. I sound like a real businessman. You asked about other people. There's a writer named Frank Stanford(6) who I really like. I'd like to see more from him. He's a poet, novelist and short story writer. He died in the Seventies.

SS: It makes me sad when you discover someone new, and want more from them, but they're gone and their work is done.

TW: You know what's worse? When somebody goes, "Isn't he dead?" And it turns out they're not dead. But you just haven't heard anything from them, so you just

assume they are dead. If you don't put out a record for a couple of years, people start circulating rumors that you have throat cancer. Or diabetes and you had one of your legs removed. Or you lost an eye in a fight. It's amazing what they manufacture. It's part of the folk process. Here's something interesting -- you know the angle between a branch and trunk of a tree? If you look at a leaf from that tree, you'll see the exact same angle on the main pulmonary leaf vein that goes down the center of the leaf.

SS: Is there a word for that?

TW: Find a leaf, and you tell me if I'm right. We're out in the sticks. Out here in the country, I like to say we watch a lot of TV. But TV stands for "Turkey Vultures." Well, I guess they're the turkeys of the vulture world. The reason they circle as long as they do is that they weigh almost nothing, and what they're really trying to do, you think they're circling and trying to land, but a lot of them are unable to land, they weigh so little. It's like watching a leaf try to land in a windstorm. At the bird sanctuary, as well as bird rescue, they say that most vultures brought in were hit by cars while dining. When they eat, they eat so much they can't take off. So if they have to leave hurriedly, they're frightened, there's caution, and they'll throw up everything they had to eat so they can get back up in the air. We've got things that we do that they probably are shocked at as well. Humiliating things we all have to do. Trying on clothes.

SS: It must be sad to be a turkey vulture. They must be unloved.

TW: I don't know if sadness is part of their world. They have a special hole in the top of their beaks so they can breathe when their head is inside the carcass

of another animal. Just like us. Their babies are white. I came across a nest of vultures in the woods. They're snowy white, what looked like little balls of fur. They're very sweet when they're young. Have you ever seen a baby pigeon?

SS: No.

TW: You never will. But they exist.

SS: I wonder why you never see birds falling out of the sky. Where do birds go when they die?

TW: There's probably one particular tree that's owned by the insurance company where they go. It's probably in Madison, Wisconsin. The tallest tree in Madison,

actually. The insurance tree.

SS: Owned by Mutual of Omaha.

TW: That's it. I find those things interesting. I get a kick out of that. I always wanted to do a voice-over for a nature program like David Attenborough does. So

I put that together and sent it to the Discovery Channel. I wanted to see if I could get some extra work. I also sent "King Kong" to what's his name.

SS: Peter Jackson.

TW: Peter Jackson! I wrote him a long letter and sent "King Kong" to him. And I said, "You probably have a spot at the beginning of the film or the end -- or

somewhere in the middle." I didn't hear back from him either. I'm starting to get nervous.

SS: I was just watching something on the History Channel on the bubonic plague -- you might have done well on that?

TW: They tried to get me involved with one of those things -- this project they're doing in England. I don't know if it's ever going to happen, but they said, "Pick a disease," and they had this long list of these terrible diseases, and they want you to write a song about this disease. Then they're going to put it all on a record. It's just gotten out of hand. I didn't want to get involved. I just said, "No, I can't pick a disease."

SS: Do you believe in self-fulfilling prophecies?

TW: I don't know. I think there are things waiting to happen. Then there's the tipping point, and all they need is your enthusiasm. Or maybe it already had the

enthusiasm of millions of others and it was waiting for one more. And you provided that. That's what the butterfly effect is -- that just the wings of a butterfly can create a monsoon. I believe in those things. Here's something interesting: I have a recording of crickets that's slowed down. That's all -- it's just slowed way down. If I didn't tell you you were listening to crickets, you'd say, "What's this, the Vienna Boys Choir?" It's four-part harmony: bass, cello, viola, and violin. It's orchestral, and the melody they're singing is the beginning of the melody for "Jesus Christ Superstar." You think I'm making that up, but I'm not. A good friend of mine, Richard Waters(7), created an instrument called the waterphone. He used to go out on the rocks and claims to have been able to communicate in some way with the whales.

SS: What did they tell him?

TW: He was just surprised that there was any call and response at all. It's an interesting instrument. You've probably heard it a lot in horror movies, but didn't

know what it was.

SS: Your film career has taken you down a lot of roads. You've been typecast in many respects.

TW: For a lot of people, it's "Go ahead, typecast me, just cast me." It's like some people say, "The only trouble with tainted money is there 'taint enough." I'm

not actively trying to alter my image in such a way so that I can play presidents or terrorists. I'm just letting it kind of go along. Now and then I get a call from somebody who has an interesting project, and you do it. I guess the ideal way to do it is to come up with all your own ideas. Movies are expensive and time-consuming as hell.

SS: Isn't music the same?

TW: Yeah. But it doesn't feel as overwhelming, because it's more in my domain. I'm like the director when I go into the studio, and I'm in it. But in a movie, you're

either wallpaper or a chair. I do some acting, but I'm not really an actor.

SS: Musically, what do you think you'll do next?

TW: We're always making new tunes up -- that doesn't ever stop. I love doing it. I love nothing better than being in a room with the door locked and the piano and

the tape recorder going. It's a great job: making up tunes.

Notes:

(1) What made you decide to tour again?: USA tour promoting Real Gone/ Orphans August 1-13, 2006. Tom Waits: vocals, guitar, keyboard, maracas. Casey Waits: drums. Bent Clausen: various woodwinds, keyboards, strings and percussion. Larry Taylor: upright bass. Duke Robillard: guitar. Further reading: Performances 2006 - 2010.

(2) Bob Moog: "Robert Moog developed his ideas for an electronic instrument by starting out in 1961 building and selling Theremin kits and absorbing ideas about transistorised modular synthesisers from the German designer Harald Bode. After publishing an article for the January 1961 issue of the magazine 'Electronics World', Moog sold around a 1000 Theremin kits from 1961 to 63 out of a three room apartment. Eventually he decided to begin producing instruments of his own design. In 1964 Moog begin to manufacture electronic music synthesisers. The Beatles bought one, as did Mick Jagger who bought a hugely expensive modular Moog in 1967 (unfortunately this instruments was only used once, as a prop on a film set and was later sold to the German experimentalist rockers, Tangerine Dream). Though setting a future standard for analogue synthesiser, the Moog Synthesiser Company did not survive the decade, larger companies such as Arp and Roland developed Moog's protoypes into more sophisticated and cost effective instruments. Robert Moog has returned to his roots and currently runs 'Big Briar' a company specialising in transistorised version of the Theremin." Further reading: Moog Music.

(3) This gal Lydia: "Being the granddaughter of Leon Theremin's first cousin, Lydia Kavina (1967) was the inventors last prot�g�e. At the age of 9 she started studying the instrument. She gave her first concert at the age of 14. She studied composition and graduated in 1992 and she finished post-graduate studies in 1997. Today Lydia is one of the few professional thereminists in the world and a master teacher on this instrument. She also is a composer and has premiered her own works and those of others throughout Russia, the USA, Europe and Asia." Further reading: Lydia Kavina Official Website.

L) Lev Theremin teaching Lydia in 1976, photo by Snegirev from Lydia Kavina Official Website.

R) Photo by Z. Chapek, 1997. From Lydia Kavina Official Website.

(4) Road To Peace: Read lyrics: Road To Peace.

(5) Creating false biographies for themselves: reminds of Laura Albert (also known as JT Leroy) who has been interviewed by Waits for Vanity Fair in 2001.

(6) Frank Stanford: Of the over ten collections of Stanford's poetry once in print, only two are available today, Conditions Uncertain & Likely to Pass Away and The Light the Dead See (1991). Called "the best poet in America under the age of thirty-five", on June 3rd, 1978, Frank Stanford shot himself three times with a .22 revolver. He was twenty-nine years old. In early seventies, he and his publisher, Irving Broughton, made a film about his life and work, It Wasn't A Dream, It Was A Flood. The film won the 1975 West Coast Film Festivals Best Experimental Film Award. Further reading: AlsopReview.com

(7) Richard Waters: Collaborated with Waits on the albums 'Moanin' Parade. Gatmo Sessions Vol. 1' and 'Swarm Warnings, Gatmo Sessions Vol. 2'. Further reading: Richard A. Waters official site