| Title: Tom Waits Source: Mojo magazine (USA), by Barney Hoskyns. Transcription as published on http://www.rocksbackpages.com. Date: China Light diner in Santa Rosa, 1999 (published February, 2000?) Key Words: Mule Variations |

Tom Waits

Few of the patrons of the China Light diner in Santa Rosa look up when Tom Waits shuffles through the door. Attired in coarse indigo denim and clutching a bulky leather briefcase, to them he's merely another street eccentric. Just as he blended effortlessly into the barfly demi-monde of sleazoid Hollywood in the days when he was bellowing songs like 'The Piano Has Been Drinking', so now - despite living in domesticated rural bliss with a wife and three children - Waits can wander into a Chinese Diner in northern California without causing a commotion.

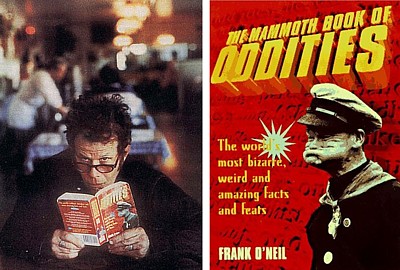

Then again, when you've sat down with the man and he's yanked a battered paperback called The Ultimate Book of Oddities(1) out of the briefcase, Thomas Alan Waits hardly looks like your average Joe. Perhaps it's the little swatch of white-grey hair beneath his lower lip, or the nest of dark red locks scrunched under his old fedora. Maybe it's the deep, growling voice - somewhere between Lord Buckley and Leonard Cohen - in which he speaks of upcoming local attractions like the Banana Slug Festival.

"They're gelatinous gastropods ten inches long, and people cook with them," he says. "They're indigenous to this area, so much so that a nephew of mine asked me to capture and send him one. We did, and it was a big hit."

The truth is, Waits doesn't much care for the interview ritual, even if this one is designed to promote a terrific new Tom Waits record called Mule Variations. It might be different if he could talk all day about banana slugs, but the realities of the modern music industry behove him to address the many ramifications of a career that stretches out over three decades. It's probably a good thing that he only releases an album every six years or so.

Recorded in a small studio(2) near Waits' home in northern California, Mule Variations gives us the 49-year-old singer in all his favoured (dis)guises, from Dada-esque bluesman to maudlin balladeer and back again. One minute his guttural groans suggest a dying Howlin' Wolf; the next he's at the front parlour upright crooning gruffly to his wife and collaborator Kathleen Brennan. Less crazed than Bone Machine (1992) or The Black Rider (1993), the album has a rough-hewn feel that screams backwater contentment. If one excepts "Blind Love", his 1985 collaboration with Keith Richards, it may be as close as Tom Waits ever comes to making a country record.

Mule Variations is certainly very different from his 1972 debut Closing Time or any of the other albums which made Waits' name in the Seventies. For most of that decade he played the part of a pie-eyed L.A. hipster who'd retreated into the pre-rock universe of Jack Kerouac and Thelonious Monk. Just how "real" the Charles-Bukowski-sings-Mickey-Spillane persona of The Heart Of Saturday Night (1974) and Nighthawks At The Diner (1975) was remains a sore point. "It's a ventriloquist act, everybody does one," he says a touch impatiently. "People don't care whether you're telling the truth or not, they just want to be told something they don't already know."

Whether it was "true" or not, Waits by the end of the Seventies had grown weary of his alcoholic-beatnik persona, and especially of the way his slurry ballads were being smothered by overly lush orchestrations. In 1982, following his superb soundtrack for Francis Ford Coppola's One From The Heart, he took an abrupt detour off Beatnik Boulevard. Producing himself for the first time, he enlisted a fresh group of musicians to help him forge a new sonic language: knotty, neo-primitivist, and completely unlike anything that was being made in that soulless, upscale decade. Inspired by cult composer and instrument-builder Harry Partch's concept of "corporeality"(3) - of sound grounded in the body - Waits made the astounding feat of self-reinvention that was Swordfishtrombones.

"I was trying to find some new channel or breakthrough for myself," he says. "It was like growing up and hitting the roof, because you have this image that other people have of you, based on what you've put out there so far and how they define you and what they want from you. It's difficult when you try to make some kind of a turn or a change in the weather for yourself."

Even those Waitsians wedded to an image of their hero wallowing in a Hollywood gutter were stunned by the brilliant eclecticism of Swordfishtrombones and its successors. Listening again to the album - and to Rain Dogs (1985) and Frank's Wild Years (1987) - what continues to astonish is just how earthy and radically lo-fi they are. At a time when pop music was being buried under layers of reverb and flangeing, Waits reduced his sound to a few antiquated keyboards, some makeshift percussion, and a guitarist, Marc Ribot, who seemed to play with a flagrant disregard for the right notes.

"I wanted to find music that felt more like the people who were in the songs, rather than everybody being kind of dressed up in the same outfit," he says. "The people in my earlier songs might have had unique things to say and have come from diverse backgrounds, but they all looked the same."

As he had always done, Waits sang of drifters and grifters, amiable losers like the bumbling trio in Jim Jarmusch's Down By Law, played by Waits, John Lurie, and Roberto Benigni. How apt, indeed, that Waits should have been associated with Jarmusch, whose dry, lowkey Eighties comedies now look like black-and-white blueprints for every hip, quirky movie made in the ensuing decade. Back in 1987, when both Down By Law and Frank's Wild Years were made, pop culture was all about Madonna and Michael Jackson, Sly Stallone and Arnie Schwarzenegger. Twelve years later, the Waits/Jarmusch aesthetic is everywhere, in every Elmore Leonard movie adaptation and every post-grunge album of skewed Americana.

For fifteen years, Waits has been a totemic figure for a generation of alternative acts who want their music to sound dirty, visceral, and human. From the gothic swamp-rock of Nick Cave and P.J. Harvey to the muddy grooves of the Beta Band and the stomping blues-punk of Jon Spencer, Waits is the hidden presence behind so much music that rages against mechanical blandness. Just as Waits himself fused Harry Partch's fantastical ensembles with the Dada blues of Captain Beefheart and the acid schmaltz of Randy Newman, so these Nineties acts have variously combined rock and hip hop with the sound of Waits' self-styled "mutant dwarf orchestra".

Perhaps what these people love most about Waits is how resolutely he's refused to sell out. (It is a splendid irony that he's probably made more money sueing companies for using or impersonating his music in ads(4) than he would have made by allowing it to be used.) It's difficult to imagine Waits rubbing cummerbunds with Robbie Robertson and Ahmet Ertegun at a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame dinner. Just as Kerouac and Burroughs were waging guerilla war against the cultural status quo, so Waits has refused to cosy up to the rock establishment, knowing how much it would compromise what he does. By his own admission, he's never been much of a joiner-in. "I'm just suspicious of large groups of people going anywhere together," he says. "I don't know why, I just always have been. If there's thirty thousand people going to see some event, I'm suspicious of it."

Waits draws on the time-honoured beat strategy of dissembling, bluff-calling, tall-tale-telling. He wriggles out of the media's grasp, refusing to be pinned down. For him, there is no "essence" of Tom Waits, no message to be interpreted. Instead, he roots himself in a tradition of "show business", exaggerating the very nature of "performance". At the same time - and here's a catch of sorts - he is one of rock's last great romantics. The same man who can rock harder than Jon Spencer is also the man who goes soft on you at a moment's notice. For every deranged outburst on Mule Variations ('Eyeball Kid', 'Filipino Box Spring Hog'), there is a gorgeous, unadorned piano ballad like 'Take It With Me' or 'Picture In A Frame'.

"I don't know if I've reconciled the two things," he admits. "I guess I would like to try and find some way to put them together, instead of putting them end-to-end. I guess they're different facets of things I'm drawn to. Or maybe it's just that you put your fist through the wall and then you apologise - the alcoholic cycle!"

One of the tracks on Mule Variations is a comically spooky piece called What's He Building In There?' - the monologue of a prying busybody obsessed with the unsavoury things his mysterious neighbour might be up to. ("I swear to God I heard someone moaning low/And I keep seeing the blue light of a TV show...") Aside from being hysterically funny, the track almost functions as an allegory of Waits' own nonconformity.

Like the man next door, Tom Waits keeps to himself, working in the spirit of someone tinkering around in a greasy workshop. In an America where any solitary activity seems increasingly to make people suspect that there's a serial killer living next door, Waits, thank God, remains a deeply private man - an introvert doing his own thing while everyone around him tries to second-guess the next big trend.

"What's he in building in there?" mutters the song's curiosity-maddened speaker. "He never waves when he goes by. He's hiding something from the rest of us... he's all to himself." Not a bad way of putting it, really.

� Barney Hoskyns

Notes:

(1) The Ultimate Book of Oddities: This would probably be "The Mammoth Book of Oddities" by Frank O'Neil. Paperback (November 1, 1996) Publisher: Carroll & Graf Publishing ISBN: 078670375X

Source: HUMO (Belgium). April 27, 1999. Date: 1999. Photo credit: unknown.

(2) Recorded in a small studio: Prairie Sun recording studio in Cotati/ California. Former chicken ranch where Waits recorded: Night On Earth, Bone Machine, The Black Rider (Tchad Blacke tracks) and Mule Variations. Further reading: Prairie Sun official site

(3) Harry Partch's concept of "corporeality": San Diego multi-instrumentalist. Developed and played home made instruments. Released the album 'The World Of Harry Partch'. Major influence for the album 'Swordfishtrombones'. Partch died in San Diego, 1974. Further reading:Partch, Harry 1; Partch, Harry 2; Partch, Harry 3; To those who know his work, Harry Partch (1901-1974) is one of the most unique creative artists in the 20th century. Composer, performer, instrument builder (some say sculptor), iconoclast, and creator of stage works that fully integrate music, movement, theater, text, and stage design, Harry Partch assembled a musical experience representing his philosophy of total corporeality. Partch's belief in "vital words" in music was only part of his larger belief in corporeality, and in his later works he seems to have relied more on other means to achieve it - the visual appeal of the instruments, the physicality of the performers, the tone colors of the music itself. He clearly still conceived of his music as theatre, but a theatre that had grown, apparently, less dependent on words. Harry Partch's work embodies the integration of mathematics, technology, and the arts. His music and instrumental design are based on a personal vision of the natural way in which ratios determine intervallic tunings and temperaments. In the service of his musical vision he employed the technology of bamboo, wood, glass, and the discarded objects of his modern time: pyrex carbouys, liberated from the trash bins of the Radiation Labs of the University of California, Berkeley, were transformed into Cloud Chamber Bowls; carefully tuned lengths of bamboo became the Boo; an altered reed organ became the Chromelodeon; miscellaneous objects from army surplus became the Spoils of War. Through his art he integrated all of this into a complete theater in which no divisions existed between instrumentalist, dancer, singer, and actor. His philosophy of a "total corporeality" permeated all that he created resulting in a magical experience unique within the 20th century.

(4) Sueing companies for using or impersonating his music in ads: Further reading: Copyright