|

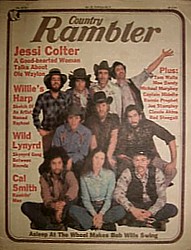

Title: The Ramblin' Street Life Is The Good Life For Tom Waits Source: Country Rambler magazine, by Rich Trenbeth. Photography by Mitchell Rose. Thanks to Kevin Molony for donating scans Date: Chicago. December 30, 1976 Keywords: Street wisdom, Musical influences, Commercial success Magazine front cover. Country Rambler magazine. December 30, 1976 |

The Ramblin' Street Life Is The Good Life For Tom Waits

The shoes are those pointy, black Monkey Ward jobs of garbage-can vintage. The dark, narrow-lapel suit looks like it was pressed by a park bench. The skinny, crippled tie is barely identifiable beneath the food stains. The white shirt looks like it was packed in a back pocket. And the tiny, tattered burlap hat has trouble holding onto the thick patch of slippery, slicked-back hair. out from under it all comes a voice that sounds like an old scratchy 78 record played at 33 1/3.

Tom Waits, the fast-rising street rambling songwriter from L.A. is in Chicago for weekend shows at the Quiet Knight(1), a small, intimate folk club that once gave a boost to such names as Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, Carly Simon and Jackson Browne.

Waits looks like he just stepped out of a shot-and-a-beer, factory-district bar, but his musical tastes dip heavily into country. He digs Red Sovine. Jerry Jeff Walker frequently uses Wait's song, Heart Of Saturday Night, as a stopper during his own shows.

The opening act is on and Waits relaxes backstage on a heavily bandaged crumbling-leather suitcase. A friend hands him a cold beer and he scarfs it down, chasing each swig with a long drag off a straight cigarette.

"You know I've been the opening act for a long time and now I'm just slowly starting to headline. It's another world. Used to open for groups like the Mothers of Invention and Cheech and Chong. I used to get all sorts of produce and crap thrown at me. Some nights I had enough to make a fruit salad."

"Since I was a kid I had an image of me in a dark sport coat and clean tie getting up and entertaining people." he says with a laugh that sounds like an old Ford pickup revving up "Even though I've had to do a lot of other things to make a buck, this is what I've always wanted to do."

Waits is 27, but you could guess anywhere from 23 to 50. With the lean look of a depression era down-and-outer and a gravely Louis Armstrong voice, he doesn't fit into any particular slot. Or generation. He's a street man. But not a street punk. While the Dylans, Stones and Springsteens meant youthful rebellion, Waits is just street life. Young and old, beginner and bum. Red, white and brown. Down and out. The ultimate city street rambler.

Waits already has several successful albums behind him, major appearances at top clubs from coast to coast and a shot on the prestigious Chicago PBS Channel 11 Soundstage(2). He is just beginning to enjoy star status.

His act can't really be compared with anything that is or was. He looks like he should be standing in a bread line during the Great Depression. His music is a curious weave of 1950's jazz walking a thin line between music and early Greenwich Village poetry. He's as comfortable snapping his fingers for an accompaniment as he is playing the piano and guitar. His voice sounds like the end result of a week-long drinking binge. And his poignant lyrics are not only from the street, but from their debris-filled gutters. He sings of the blues. His lyrics describe the gritty reality of street life in a humorous way. He hits the all-night cafes and comes out with "enough gas to open a Mobile station." When he runs into a cold streak with the ladies, "even the crack of dawn isn't safe." And he's been stuck in small towns "where the average age is deceased."

Waits doesn't play the big concert halls because his music needs the mood-setting, small, intimate clubs. You must be close enough to catch the little nuances, like the way he works over a cigarette or shakes his head or laughs. You get the impression that you're in a neighborhood bar. In most performances when he forgets to light the cigarette dangling from his mouth, someone from the audience will casually rise to give him fire.

Unlike most of today's country and pop stars who prance about singing of the common man and life in the streets while they live the reality of champagne and 30-room mansions, Waits prefers his pocket pint of whiskey, ham and hashbrowns in a greasy-spoon cafe. And it's not just publicity.

For the last six years, home has been a one-room $135 walkup on the outskirts of L.A., where he cooks on a hot plate and watches his old black and white Philco TV. When he's home, which is only about four months of the year, he spends his time mingling with friends in workingmen's bars. "Most of my buddies are regular workingmen, hacks. And many really don't understand why I'm gone from home so long," he says, guiding a drooping ash into a dead beer can.

If his songs capture the gut-feel of city street life, with its raunchy cafes and hardluck hustling. It isn't because Waits is just a good voyeur. Since high school until his music began supporting him five years ago, he was in the thick of the hustling himself. His experience reads like a page from the want ads. He's driven a cab, worked in a liquor store, was a fireman, cook, janitor, night watchman, worked in a warehouse, jewelry store and drove an ice-cream truck.

He was raised in L.A. In a heavily Chicano and Oriental neighborhood and admits with a long rumbling chuckle, "When I was a kid, I was pretty normal. Used to go to Dodger Stadium, was a real avid Dodger fan. I did all the usual things like hang around parking lots, had paper routes, vandalized cars, stole things from dime stores and all that stuff."

He admits he lives in self-imposed poverty and doesn't have much of a hard-luck story to tell about his growing up. His family didn't have a lot of money but they got along okay. His father was and still is a Spanish teacher in downtown L.A.'s Belmont High. But young Tom was more interested in learning another "foreign" language. The Vernacular of the street.

Street wisdom is something that for a lot of people is inherent. You build on it and become street-wise after awhile. You can usually spot somebody with it and somebody without it. I seem to fall in with people who I know have it. After awhile you learn certain things, certain expressions. You can communicate on a level most people don't understand. Expressions like 'Harlem tennis' - a crap game. And the highest hand you can get in poker is 'deuces and a razor blade.' A 'crumb crusher' is a baby. 'Face' is a good-looking kid or a nice looking doll. A 'fat man' is a five dollar bill. And 'He went up north for a nickel's worth' means he went up north to jail for five years - usually for armed robbery. I learned that when I was in jail. I go there a lot and they just know me. I go to the Barb Wire Hotel in L.A. for minor violations like drunk driving, being a public nuisance. Expired driver's license, jay-walking tickets."

Popping open a new beer, he continues. "A lot of the vocabulary is just inner sanctum - it stays in the streets, but a lot goes out to the suburbs. That happened a lot in the '60s with terms like reefer. Suburban parents started getting uptight about drugs all of a sudden. They had the attitude that we don't mind drugs, just keep them in the ghetto. We don't want them in our neighborhood - keep their vocabulary and problems out."

Rapping, Waits draws heavily from the streets, but musically, his influences take some unexpected detours. He admires Jerome Kern, Gershwin, Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, George Shearing, Oscar Brown jr., Lord Buckley, Peter, Paul and Marry, and Mississippi John Hurt. "My musical influence of songwriters were guys who are either old or dead and just not around anymore. They're a real incongruous group that somehow I had to fuse together," he says with an incredulous look.

The group's bus is impatiently revving, horn honking, because they were scheduled to leave immediately after the Quiet Knight show and head for the East Coast. Waits' manager saunters backstage to remind him that the guys have been waiting and are ready to go.

"We will but the boys will just have to be patient," he tells him and then returns to the conversation with Rambler. "I first got on stage in a small club in San Diego. It was a folk club where I got "blue-grassed" to death. I was working the door, taking tickets at the time and listening to all kinds of groups. The reason I got the doorman job was because I knew I was going to play there. I was sitting there incognito - like in the inner sanctum of this club, hob-nobbing, doing some low-level social climbing. I knew one day I would perform myself, but I was trying to soak up as much before I did so I wouldn't make an ass of myself."

Although he started as a solo act playing both piano and guitar, today he performs with a backup of standup bass, tenor sax and drums. It provides him with a rhythmic, finger snapping background that forms a perfect frame in which to place his quick-driving lyrics.

Waits traveled to New York to round up his group because he felt the West Coast was loaded with too many slick studio types, and he wanted musicians who lived and breathed the old club circuit. "In New York there's still a healthy club scene. These boys know how to wail in the blue smoke," he says, lighting another cigarette and appropriately blowing a lazy cloud toward the ceiling.

"I found myself three previously unemployed bebop musicians. Except my tenor(3) used to play with Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman - he's been around the block several times. My upright player is Dr. Fitzgerald Huntington Jenkins III. It's nice to have something to fall back on. He was a doctor and went to a concert, saw an upright player and went out. He quit his internship, split for Europe and studied bass with a guy. And my drummer(2) grew up in Harlem in a drumming family. He was weaned on brushes. I got a black bass player, a Sicilian tenor and a Cherokee and Afro-American drummer. We can go into any neighborhood in the world and hang out."

During another Chicago appearance Waits and the group stayed in the seedy Transients Welcome uptown hotel. And they could be found downing shots and beers in places where you take your life into your hands along with your drink. A heavily poor Appalachian and Puerto Rican area where you're liable to find as many sitting in the gutter as in the dingy bars and cafes, uptown gave Waits an abundance of material to put into a song. "I used to go to the Victoria Cafe(4), which was only half a block away in a Puerto Rican neighborhood. But half-a-block in a Puerto Rican neighborhood is half-a-mile. I was scared to death. Kept my money in my sock and walked quickly," he laughed, tugging at one of his socks.

"I don't do a lot of hob-nobbing with household words. It's hard to keep one foot in the street because of how this business can be and this whole American Dream. There are different criteria for success - like the American credit card. But for me life in the streets is much more fascinating."

And if anyone should know, Tom Waits should. "I may go to 50 cities in four months and I got friends in Chicago, New York, Montana, Madison, Wisconsin, New Orleans, Seattle, Portland, San Diego, Phoenix, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Bangor, Maine, and oh, yeah, Texas. That Texas scene is something else these days. I love those Red Sovine(5) songs."

Is Waits' rising popularity beginning to make the street man well-to-do? "I'm not on easy street by any sense of the imagination. I'm a rumor in my own time. I couldn't even begin to tell you how much I'm making, but I am making more than when I was driving a cab. I feel at times I'm residually in jeopardy with my record company. I don't pull in a lot of dividends. Most of the money I make is from personal appearances and I spend most of that on the band and the bus. I made it to 169 on the record charts and figured if we could only get to 200 it would be great. But I found out it goes the other way. No I don't know exactly how much I'm making."

What would happen if all of a sudden Waits made it really big and started raking in the money? "If I had a lot of money I'd probably get even more eccentric than I am now. I'd probably have a complete reversal."

What would happen if he was offered his own TV special, like John Denver? With a multimillion-dollar contract. He didn't hesitate: "I'd move into the Apollo Hotel in Philadelphia and pay my room up three weeks in advance. I don't know what I would do with a lot of money. Well, probably the first thing I'd do is buy a new sport coat and a pair of shoes."

Notes:

(1) Weekend shows at the Quiet Knight: unidentified shows. Further reading: Performances

(2) Soundstage: TV concert appearance for "Soundstage", Chicago. PBS television show on Tom Waits and Mose Allison. Chicago/ USA (aired December 22, 1975, recorded November 3, 1975 or earlier). (Source: "Wild Years, The Music and Myth of Tom Waits". Jay S. Jacobs, ECW Press 2000)

(3) My tenor/ my drummer: Frank Vicari: tenor saxophone. Chip White: drums/ percussion. Further reading: Who's Who?

(4) Victoria Cafe: read this Downbeat interview held at the Victoria restaurant, Chicago 1976

(5) Red Sovine: "Big Joe & Phantom 309": Live intro from "Nighthawks At The Diner": "Well now, it's story time again. I'm gonna tell you a story 'bout a truck driver. This story was written by a guy named Red Sovine, and it's called the Ballad of Big Joe and Phantom 309." Actually this song was written by Tommy Faile. Sovine made it famous.