|

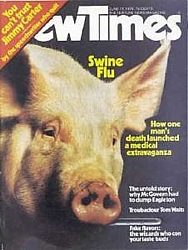

Title: Play It Again Tom Source: New Times magazine (USA), by Robert Ward. Photography by Neil Zlozower, Michael S. Gordon, Chuck Pulin Date: Unicorn Club, Ithaca/ New York. Published: June 11, 1976 (Volume 6, number 12) Keywords: John Frenchette, Literary influences, Shaboo Willimantic/ Connecticut Magazine front cover. New Times magazine (USA). June 11, 1976 |

Play It Again Tom

by Robert Ward

Scat-singing, dice rolling, song-writing Tom Waits is on the road in his '55 Cadoo. And in his suitcase of songs are the ghostly tunes of old cocktail piano players and the jazz riffs of Beat poets.

Tom Waits is crushed. The eclectic singer/ musician is sitting in the stale-aired dressing room of the Unicorn Club in Ithaca(1), New York, and he can feel the whole damned room pressing in on him. He's tired and his mouth is dry, in spite of the Heineken brought to him by the nice waitress in the black tights. He's feeling spaced and dizzy, and he's coughing like a 70-year-old wino stevedore down for the last stroke. Frank Vicari, Waits' tenor man, and Chip White, the young Cherokee drummer who is always awake and excited, and Dr. Fitzgeralde Huntington III, the bassist, are bopping about the little cell of a room like a trio of mad bats. Waits is watching them from between two fingers he has pressed over his eyes, watching them as if he were staring through Venetian blinds in the potted palm lobby of some cheap hotel. Is this what stardom is all about? Is this all there is? Is this like "anywhere"?

Waits road manager, John Frenchette(2), introduces me to the band and Tom Waits, Asylum's new big hope, a cult figure for the seventies. Little and savvy and street-tough. Like Springsteen, he oozes punkdom, but a slightly different brand. Literate, intelligent, Waits is musically influenced by old cocktail singers like Mose Allison, eloquent songwriters of the forties like Johnny Mercer ("One For My Baby and One More For The Road") and swing blues masters like Count Basie. He also manages to sound like Dave Van Ronk (the gruffest street-voice Jack, whoa), Louie Armstrong and Frank Sinatra (catch Waits' song Drunk on the Moon").

Waits stares up at me and nods his head.

"How you doing?" I say, gazing at this skinny little multi-voiced, multi-selved and multi-talented 27-year-old jive artist.

Waits looks at me again, one eyeball opening.

"I'm a success," he says. "Success without college. Driving 12 hours, the bus breaks down...." He shakes his head, and his rakish po' boy cap falls over his closed eye.

"Where did you break down?"

"By the side of the road. By the side of the road. Always by the side of the road... the side...."

Waits is scat-singing, scratching his crotch, still sitting slumped like the last Korean War vet left in the V.A. hospital. Twenty-seven going on 52. "I was hoping we could talk."

"Yeah, great...in between shows. Just remember, I'm a rumor in my own time. Or is it a tumor in my own brain."

Waits smiles and shuts his eyes.

I wonder if there will be a show. The kid looks too small, too weak, too anemic to get up on a stage; what he needs are urgent glucose shots, not a three-hour two-set gig. The lights go down and the band members stroll onstage. Not jumping like the Stones, not strutting confidently like the E Street Band, but as if they were out for a walk on a breezy, late afternoon. And then the spot is down, and then, and then.... Tom Waits is bopping out front while Frank Vicari, who says he used to "like blow with Maynard, Woody, Diz and Prez(3), you know what I mean, Joe," very coolly puts the reed into his mouth and sucks in air, his greying electric Afro standing on end. A cool breeze of sound wafts across the spacious wood-paneled hall.

In Waits' hand is this old suitcase with its fashionable travel stickers fashionably half torn off. The kid is almost as beat looking as he was in the dressing room, with his belt sort of crooked, his brown tie so cheap it glistens and his threadbare black sport coat, also glistening. CHEAP, baby. This boy is a Bible salesman on a cheap shot to nowhere. At least that's the bit, and it all depends on whether this fellow with a half-assed scraggly beard can put it across.

Waits stands at the mike and goes into a little soliloquy. Behind him the bass player is uprighting right along, so very coooool, Jim, so very fine, Jack -- boomboomboomboom, whapwhapwhapwhap -- and Waits is snapping his fingers and popping his body in time with the beat. That scrawny, wasted, pasted, sparrow-boned body jerks and moves, and the crowd sits there looking at one another, and then Waits starts in with his lines, half-talking, half-singing, sounding like Louie Satchmo, like Dave Van Ronk -- like Tom Waits.

"We been on the road." "Boomboomboomboom!" "We been on the road so long, man, you get home and everything in your refrigerator looks like a science project." "Boomboomboomboom!" The bass player is smiling, the tenor man aloof and blowing. "It's good to be busy." "Boomboomboomboom!" "It's good to be busy, and we been busier than a pair of jumper cables at a Puerto Rican wedding, Jack. You know baby, ahooooo." "Boomboomboomboom." And the sax does his thing. "Wah oh wah oh."

And it's a bit like sitting in Birdland listening to Prez and Diz and Bird blow, baby, while outside it's drizzling muck and 15 dudes with runny junkie noses and trench coats slouch next to the big doors with the stars' 8 x 10 glossies slapped on them.

The lights go down and the band goes into "High on the Moon," a soft, lyrical ballad. Waits plays his piano, and while this isn't Thelonius Monk, it's not pedestrian either. Nice touch, nice feel, nice pace, very nice all around. But Waits' real forte is words. The man can write lyrics:

Tight clad slack girls On the graveyard shift 'Neath the cement stroll Catch the midnight drift Cigar chewin' Charlies In their newspaper nests Grifting hot horse tips On who's running the best

And I'm blinded by the moon Don't try to change my tune I thought I heard a saxophone I'm drunk on the moon.

On the word "saxophone" Frank Vacari blows, man, and Waits shuts his eyes and rocks back and forth, and the listener's transported right out of the room to Rick's Cafe where Sam is hunched over the piano, the cocktail man, urbane and chic and beautifully ruined.

The music calls forth a vision found in movies of the forties and fifties. It's a vision of all-night talks among would-be novelists and poets in New York cafeterias, of lonely World War II sailors standing out on Front Street hoping for love but settling for a pint of rot-gut rye and a flophouse floozy -- the stuff mined by novelists like Nelson Algren, directors like Elia Kazan. And yet, that's not all there is to Waits' music. He takes the American loser/hero -- the cocktail piano player, the wise-assed smacked-around rogue who plays the nags and loses the winning ticket -- and infuses the figure with new life, in a style that is at once nostalgic and completely contemporary.

Of course, everyone doesn't think so. In Rolling Stone and other journals, Waits has been given a bad rap because he likes to do scat songs, because, with near free-verse poem-songs like "The Ghost of Saturday Night," he is consciously reviving the old Beat poet-jazzman's collaborations. It's true that those hearing the tunes makes one think of Gregory Corso or Allen Ginsberg reading their poetry while Philly Jo Jones lay down some drums and maybe Gerry Mulligan blew sax; but why should anyone criticize Waits for wanting to revive that form? The question, after all, isn't whether it's NEW NEW NEW but if it's authentic. And Waits' music is authentic.

In his Unicorn performance, Waits' version of "The Ghosts of Saturday Night" and a long talking number that appears on his new album, Nighthawks at the Diner(4), are superb. The jazzmen obviously love the kid. They play in perfect sync with him, and as he sweats and shakes and lets the words fly, there is a moment when the stage is magical, spinning not out of control but pleasantly and beautifully like a great patched-up lyrical balloon.

The solitary sailor who spends the facts of his life like small change on strangers, pauses in a peacoat jacket for a welcome twenty-five cents, and a last bent butt of a package of Kents

As he dreams of a waitress With Maxwell House eyes With marmalade thighs And scrambled yellow hair....

Great wordplay and great energy combined perfectly with the sax and bass create a hypnotic, joyous floating sensation. Waits has an advantage of his Beat predecessors, because he is first a songwriter. He makes the words and music fit. The Beats, in spite of their claims to spontaneity, had very little feel for words put to music. For the music of language, yes, but one or two listens to any of the old Beat-jazz combos tell you that Tom Waits is not merely cashing in on nostalgia. He is improving on the form.

Tom Waits cruises through his first set and bops off to the dressing room. When I enter to say hello he is shaking his head:

"Where are we?"

The voice is gruff and strangely mannered, as if Waits were in practice for old age. One feels it cannot be his natural voice at all.

"You're in Ithaca, Tom," someone says. "Good, just wanted to make sure. Was anybody out there?" "They liked you, Tom."

Waits smiles and shakes his head.

"No, they didn't, man. They didn't know where I was coming from. They only laughed when I got dirty."

Frank Vacari ambles back and sits down next to Waits. In the tradition of the coolest "bebop" musicians, he is "under control."

"It was like an oil painting out there," he says hoarsely.

"Not that bad," says manager John Frenchette.

"They didn't understand where I was coming from," Waits says. "Reminds me of Mose Allison. He's great, right? But he just got dropped from his label at Atlantic because people couldn't put an easy tag on him. Well, he's not a blues singer, exactly. And he's not really progressive jazz, exactly, and he's not pop. So they get nervous and drop him."

Waits shakes his head, curls his feet under him and looks for all the world like a boozy leprechaun. I sit down, accept a smoke and we talk.

"I started listening to music at a very young age," Waits says. "In fact, I was born at a very young age."

He smiles, nods his head and furrows his brow.

"Very young -- and it was like George and Ira Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cab Calloway, and the old Nat King Cole Trio -- I always liked that sort of trio sound."

"Some critics I've read put you down for being part of the nostalgia market."

Waits shakes his head again.

"I remember that interview in Rolling Stone(5). It's okay. The guy who wrote it has two broken arms now. Of course, I had nothing to do with it. I can verify my whereabouts every moment of the night and day. But, really, that article's not fair. I like this style of song. I dug the old songs by Johnny Mercer. I always played them. But I do other stuff, too. Take a song like 'Ole 55.' That's not just nostalgic, I drive a '55 Cadillac. That's the car I've always driven. It has nothing to do with nostalgia. That's why I never do any oldies. You can't improve on 'Minnie the Moocher.' Cab Calloway did it best. I'm not going to do anything old until I think I can do it better. I'm not at all into the musical retread tire scene, like say The Manhattan Transfer or The Pointer Sisters. They're just ripping off the past."

I ask Waits about his use of jokes.

"Well, jokes loosen everybody up. That what was disappointing about them out there tonight. They only related to my crotch jokes. You bring them out if nothing else is going over. Hell, I like jokes, and I even like hecklers...they get things cooking sometimes. If somebody is screaming at you, you can say, 'Say, mister, are you married?' He says yes. And then you ask him if he has a picture of his wife, and if he says no, you say, 'Well, would you like one?" and reach for your wallet. Something like that reminds you you're in a club. I love the glasses tinkling, the lights, the whole scene. I don't like it if there's just the arteest and the audience."

Wait smiles, puts out his cigarette on his prop suitcase and winks. A young boy comes into the dressing room and introduces himself as the brother of another musician. Waits is delighted.

"Sure, I remember you. What's happening with Bill? We were on the road together in Buffalo and I talked him into getting tattooed."

"Let's see yours," the kid says.

"Naw, not right now." Tom replies. "I'd have to undress. It's across my shoulders and chest. An American eagle, though with this body it looks more like a robin."

The band breaks up, and Waits is rambling again.

"Got a bad taste in my mouth. I been drinking anything, man. Sucking on cleaning products, slurping down Janitor In A Drum."

I ask him if his lyrics are influenced by the books he reads.

"Yeah, well, I was always a reader. That makes me a little different, I guess. I love Nelson Algren's work, and I love Charles Bukowski, the poet. He has this new novel out, Factotum, and it's terrific. Talks about all the lousy jobs he had to take to be a poet. Lemme see. Oh yeah, I like Johnny Rechy: City of Night, Numbers and The Fourth Angel. Rechy is writing a script based on City of Night and I might get involved doing the music. He's another one who was never fairly appreciated."

A student reporter with an oversized notebook comes in, sits at Waits' feet and asks Tom where he got his first break.

"My first break was a set of disc brakes," Waits says. "No, really, I started out playing a country club in Los Angeles. The golfers would come in wearing their doubleknits and saying stuff like, 'Uh, got me a 22 handicap and shot a double birdie on the rise, er ahhhhh,' and I'd be over there in the sand trap piano bar trying to play original tunes. I lasted one night, and made ten bucks because one lady asked me to play "Stardust," which I happened to know. A bad start. I slept a lot after that. Slept right through the sixties. Never went through an identity crisis, never had no Jimi Hendrix posters on the wall, never ate granola, never had any incense. I was like a lion ready to pounce on the music scene, but I ended up being a short-order cook and janitor in San Diego...good day job, real steady...sweeping every day, just lucky, I guess."

"Do you get depressed when people misunderstand your music?" I ask.

"Well, no, if you mean do they have to know my musical traditions. No. Music, thank God, ain't school. There are no prerequisites. You either get it or you don't. Last night they loved us in Willimantic, Connecticut(6). I guess the people around here must be into the Blue Oyster Cult."

As he continues it becomes clear that, like all good monologuists, he is really talking to himself, working out which riffs to use onstage, sorting through a mental junkpile for the right lines. Waits is a natural wordsman and everything about him -- his taste in literature included -- stems from the forties. But he admires some of his contemporaries in the rock scene, particularly those who emphasize lyrics.

"I like Martin Mull(7). I like his whole bit with the easy chairs, and I like his music. He's an ex-teacher. I have some of that in my family -- my father teaches Spanish at a high school. Bonnie Raitt, Jerry Jeff Walker, Guy Clark...all good songwriters. The song is very important, and I don't relate at all to disco, which is barely music. I'm not out to get on the stage and be a spectacle; it's the work that's important."

Another student comes in and stares at Waits adoringly.

"Is your life different now?" the kid asks earnestly. "I mean since you had a hit record."

"Which one you talkin' about son?" Wait says in a perfect Southern accent. "The last album, Nighthawks, was booming along the charts and it got to 169, and then I got real excited when it hit 200 until someone told me it was supposed to be going the other way."

Wait smiles and curls up in his chair. He's loose and enjoying himself, yet he looks as though he's going to collapse.

The waitress, a nice girl who says she is an anthropology major, comes in and gives Waits a beer. He offers to shoot her craps for the tip, and she blushes when he starts juggling a pair of dice.

Waits springs up and rolls the red dice of her serving tray.

"Seven," he says. "You lose."

Quickly he fishes in his pocket and gives her a dollar.

"Just a lit-el joke, love," he says in a prefect Mayfair accent. "You know, we are taking the whole bloody band on a trip to the continent(8). Going to be staying at mother's summer palace. A modest palace, merely one and a half turrets."

The band breaks up again and peeps out the door.

"Big crowd," says Vicari.

"Yeah," Waits says. "we'll give Ithaca one more chance."

Outside, the crowd is bigger than before, and a lot drunker. There are Cornell and Ithaca college students, and some older people, many of them the type of mustachioed men who may have once dug Oscar Peterson, bebop and the cool piano voice of Hoagie.

This time when the band appears there is a good round of applause, and when Tom Waits bops onstage there is shouting and laughing.

"Uhhh, I say, it's been cold on the road," Waits says, the bass starting behind him. "Colder than a Jewish American Princess on her wedding night. Colder than a flat frog on a Philadelphia highway on the fourth of February. Cold. uhhh...."

He pulls up his coat collar, reaches into his pocket for a Heineken, lights up a cigarette and gets the fingers snapping...and this time the audience is with him. Next to me a couple of young guys start laughing, slapping hands, snapping their fingers.

"Oooooh, that wind, ole Mr. Nighthawk," Waits growls. "It comes up to me and says, 'Waits, you got to move, boy,' and the moon, the moon is rising out of a manhole cover and we...we talk on a reg-u-lar basis."

And the crowd is starting to yell a little, like in the old days of fifties jazz.

"Yeah, yeah, and go, " and Waits' body, tired and small, is suddenly transformed, and he looks like the roughest, wiriest newsstand boy on the block, and he's cutting into his late-night flying freeway song, and the boys behind him are smiling and leaning into it, and it all keeps coming on through the night, one good tune after another, and when he tries to leave his fans are on their feet cheering and screaming, so he's back, doing up "The Heart of Saturday Night," and we are all out there in the audience rooting for him because he's made the leap over the edge. He's not a nostalgia hype and he's not a mere cocktail singer. The audience's enthusiasm and his own radiant, wiggy energy have fused and he has become fully himself. And there's a lot there, a lot of Tom Waits. If he has any luck at all, and if the audiences catch up with him, he's soon going to be the front-liner wherever he plays. He's got one vote here, dads, 'cause Tom Waits is...if you can dig my drift, Charlie... ah, like copacetic!

Notes:

(1) Unicorn Club in Ithaca, New York: unknown/ unidentified show

(2) Waits road manager, John Frenchette: should probably read: John Forscha. A 1978 Relix article has this spelled as John Forchay (Sleazy Rider - A man who works at being a derelict RELIX magazine by Clark Peterson. Extended version of "Tom Waits The Slime Who Came In From The Cold" (Creem magazine. March, 1978). Date: May - June, 1978. Vol. 5 No. 2). "John Forscha, folk guitarist. Also worked with Judy Henske: Credited on the album 'Small Change', 1976 (The Nocturnal Emissions, N.Y.C.). Road manager for the 1976 Small Change tour."

(3) Prez: Nickname of saxophonist Lester Young

(4) His new album, Nighthawks at the Diner: album released: October, 1975

(5) I remember that interview in Rolling Stone: unknown/ unidentified interview/ review

(6) Last night they loved us in Willimantic, Connecticut: May, 1976: Shaboo Inn. Willimantic/ USA. This performance is best known for the bootleg "The Heart Of The Shaboo Night". The Willimantic Shaboo opened in 1971 and closed its doors in 1982. It made its comeback in 1998 as Shaboo 2000 in Hartford/ CT

(7) I like Martin Mull: Martin Mull and Tom Waits were close friends with a compatible sense of humor. Both were musicians doing little comedic bits in between songs. Waits appeared on the 1977 Martin Mull album: "I'm everyone I've ever loved "(ABC/MCA AB-997). Mull's first break in television was on "Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman," which he describes as the "Roseanne of the 70s." Since then he has also done over two dozen feature films. Mull was a teaching fellow and has a Master's degree in art and has since stayed in touch with the medium both through painting or drawing. Check out this site for some artwork by Mull. For more information on Martin Mull, please check out this excellent: Unofficial Martin Mull Homepage

Waits did a spoken word piece with Mull ("Martin Goes And Does Where It's At" from "I'm Everyone I Ever Loved": ABC/MCA AB-997, Martin Mull, 1977) and Waits guested on Fernwood2Night and America2Night, both hosted by Martin Mull.

(8) We are taking the whole bloody band on a trip to the continent: Wait's Europen debut at Ronnie Scott's May, 1976 (UK, The Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark)