|

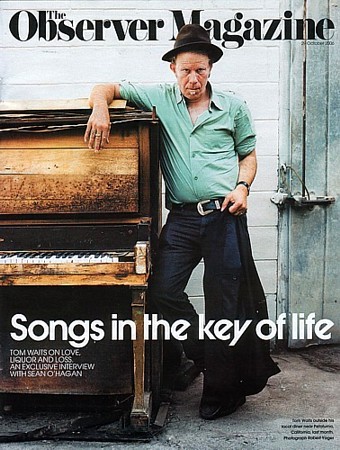

Title: Off Beat Source: The Observer Magazine (UK), by Sean O'Hagan. Transcription as published on The Observer. (Guardian Unlimited � Guardian News and Media Limited 2006) Date: published October 29, 2006 Key words: Orphans, childhood, Road To Peace, touring, Kathleen, drinking, Leadbelly Magazine front cover: The Observer Magazine. October 29, 2006 (late edition). Photography by Robert Yager |

Off Beat

For years, he was the booze-soaked bard of the barstool, the keeper of 'a bad liver and a broken heart'. But Tom Waits was saved by his wife, hasn't had a drink for more than a decade and, at 56, is making the music of his life. Interview by Sean O'Hagan.

When Tom Waits was a boy, he heard the world differently. Sometimes, it sounded so out-of-kilter, it scared him. The rustle of a piece of paper could make him wince, the sound of his mother tucking him in at night might cause him to curl up as if in pain.

'It wasn't a cool thing,' he says, shaking his head lest there be any doubt. 'It was a frightening thing. I mean, I thought I was mentally ill, that maybe I was retarded. I'd put my hand on a sheet like this [rubbing his shirt] and it'd sound like sandpaper. Or a plane going by.'

He is rocking back and forward on his seat as he recalls this and you can tell that traces of it still linger. 'I think I was having a spell,' he says, his creased, weather-beaten face crinkling even more. 'It would descend upon me at night when the house got quiet, and I'd say to myself, "Uh-oh, here they come again."' He rocks some more. They? I say, surprised. Did he think he was possessed?

'I really didn't know. Couldn't figure it out.'

Did he tell anyone? 'I think I told my mum. I'm not sure. See, I thought I'd outgrow it. Like acne. Or masturbation.' And he did eventually, though the thought of it still haunts him. 'I've read that other people, artistic people, have experienced it, too,' he says, still rocking. 'They've had periods where there was a distortion to the world that disturbed them.'

So, here we are, 50-odd years later, and Tom Waits has made a career out of distorting the world in an often disturbing way. His songs often sound like they have been bashed out of shape, put through a wringer, then left to dry in the sun until they are parched and somehow pure of spirit. On his new album, Orphans, which is really three albums in one, he grabs hold of a few songs belonging to other singers. Daniel Johnston's 'King Kong' becomes a bestial howl of despair, even more odd than the original. He scares the daylights out of the Disney standard 'Heigh Ho', from Snow White, turning it into what sounds like a slave song set to the pounding of an ogre's hammer. 'I like to go for that broken-down feel,' he says, 'the disintegration of it all.'

Orphans is a big, sprawling map of disintegration, a triple album containing 54 songs, 30 of which are brand new, while the rest have been gathered up from various one-off projects, film soundtracks and stage plays. His wife, Kathleen, once said there were two types of Tom Waits songs, 'the grim reapers and the grand weepers', but Orphans suggest there are at least three. 'Brawlers' is made up of blues stomps and raw rockers; 'Bawlers' is full of those beautiful, broken-down ballads of his that always sound oddly familiar, and 'Bastards' is a series of fits and starts, noisy outbursts that range from the cantankerous to the unhinged.

It's the first time in over 20 albums that Waits has divided his music along such generic lines. I figure that, at 56, he's finally mellowing out. 'Don't know 'bout that,' he says, sounding even more gruff than usual, maybe a little offended. 'Just thought it would make for easier listening if I put them in categories. It's a combination platter, rare and new. Some of it is only a few months old, and some of it is like the dough you have left over so you can make another pie.'

And one song stands out. Called 'Road to Peace' (1), it concerns the Middle East conflict. It's not the kind of song he usually sings, though his last album also contained an anti-war song called 'The Day after Tomorrow'. This one is angrier. 'I was pissed off,' he sighs, rubbing his eyes. 'Started with a line I read in the paper one day: "He studied so hard it was as if he had a future." It was about this kid who got blown up in a suicide bomb on a bus in Israel. They say God doesn't give you anything he knows you can't handle. Well, I don't know if I believe that.'

He'll probably get his ass kicked, I say, for the line '... why are we arming the Israeli Army with guns and tanks and bullets?' He nods. 'Maybe. Maybe. But, we are. That's just a fact.

I guess any time anyone from outside a situation voices an opinion, it's going to be, "Who the fuck are you?" Don't matter what side you're on. But this song ain't about taking sides, it's an indictment of both sides. I tried to be as equitable as possible.'

The places and the incidents referred to in the song are all real, and the names of the people, too. He's well aware, he says, of the risk of making a song carry that kind of weight. 'I don't really know what a song like that can achieve, but I was compelled to write it. I don't know if any genuine meaningful change could ever result from a song. It's kind of like throwing peanuts at a gorilla.'

Waits talks like he sings, in a rasping drawl and with an old-timer's wealth of received wisdom. It's as if, in late middle-age, he has grown into the person he always wanted to be. His tales are often tall, and his metaphors and similes tend towards the surreal. 'Writing songs is like capturing birds without killing them,' he quips. 'Sometimes you end up with nothing but a mouthful of feathers.'

We are sitting out the back of the Little Amsterdam oyster bar(2), half an hour's drive north of Petaluma, where they filmed Peggy Sue Got Married. It's the only diner with a windmill out front. Tom's kind of place: a slightly run-down Dutch diner where Mariachi bands used to play at weekends until the owner's entertainment licence was revoked after he got busted for having an illegal trailer park out the back. Tom's signed the petition like everybody else who passes through.

Outside, as far as the eye can see, there are gently rolling sun-burnished hills, tall trees, grazing cattle. It could be Tuscany except for the sign that says 'Open for Hamburgers'. This is Tom's home turf. He lives further on up the road somewhere, on a ranch deep in Napa Valley near Santa Rosa. These days, Waits does not stray far from home; the musicians come to him. His tours tend to be short, and not very often. 'Gotta keep 'em hungry,' he quips. 'You know what they say, "Don't feed the dolphins or they'll poke a hole in your boat next time you go out."'

Around the back of the Little Amsterdam, near the ancient rubbish bins and the furniture that has died from overuse, we are seated at a rickety table beside an old broken-down, rain-warped piano. Waits is drinking black coffee from a paper cup, wearing a suit at least one size too small, scuffed biker boots and a weather-beaten look that says, 'I've seen it all.' His hair is thinner now, but still has a mind of its own. His guitar is nestling in a case on the tarmac, on which rests a well-worn porkpie hat. He could have just stepped out of one of his own songs.

'Just look at this piano,' he says, the voice low and hoarse, and just the way you'd imagine it to be from his singing. 'Why has this piano been left out in the rain? It will never have a song pass through its chambers again. That's a sad thing, right?'

I look at the piano, discarded and battered beyond repair by the elements, and I nod. It is a sad thing. Sad enough to end up in a Tom Waits song. This is exactly the kind of place where the famously wayward piano in 'The Piano has been Drinking (Not Me)' might have ended up. Coincidentally, we've just been talking about drinking, and about losing your way in the fog that can sometimes settle on a life when a person loses track of where he is, who he is, and where the hell he was going.

Way back, when I first stumbled on Tom Waits while rooting though a friend's record collection, every song seemed to be about drinking and losing your way in the fog. His first record was even called 'Closing Time', but it sounded more like a lock-in at the loneliest bar in the world. Just Tom in the corner slumped over the piano serenading the last few nighthawks with his slurred songs about heartaches and hangovers, and the girl that got away.

His persona had already been perfected by the time he started living in the Tropicana Motel in Los Angeles in 1975, a faded establishment that also housed a couple of aristocratic junkies and several call girls who worked Sunset Strip. For six albums on Asylum Records, from his aforementioned debut in 1973 to 1980's Heartattack and Vine, Waits was the gravel-voiced, beer-stained bard of the barstool, a latter-day beatnik with a bad liver and a broken heart, whose fans were few and far between, but utterly devoted. And, boy, did he pay his dues.

'I opened for Frank Zappa, for John Prine(3), Martha and the Vandellas, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee,' he says now, sighing at the memory of those never-ending tours, the Godforsaken juke joints and the bounced cheques. 'I even opened for Buffalo Bob. Got to take it where you find it.'

Buffalo Bob, for the uninitiated, was a children's television star who made his name in the Fifties with an old-fashioned puppet show. 'Used to watch him when I was four years old,' laughs Waits. 'Now I'm opening for him in Atlanta. Every night he'd fill my piano with candy. Used to call me Tommy. I got him in a headlock one night, said, "You call me Tommy any more, I'll snap your head off."'

Back then, I saw Waits die a slow death in Ronnie Scott's(4), during a residency that nearly drove him over the edge. 'Supporting Monty Alexander,' he says, dryly. 'Got in a fight with Pete King [the promoter]. We didn't see eye to eye. I was young and naive. I was new to everything and far from home.'

For a long while, it looked like Waits would remain a cult figure, out on the furthermost horizon of the Seventies music scene, a stumblebum troubadour raised on bourbon and Bukowski. His music suggested and, to a lesser degree, still suggests, that the Sixties utterly passed him by; that, in his self-contained universe, the Beats were far more important than the Beatles, and Sinatra took precedence over the Stones.

'You imitate what you grow up around,' he says, when I mention this. 'If you grow up around Sinatra, Crosby and Louis Armstrong as a kid, it goes in and stays in. But some of that Sixties stuff went in too.'

He was born Thomas Alan Waits in Pomona, California, on 7 December 1949. Both his parents were schoolteachers, but his comfortable middle-class childhood was ruptured when they divorced in 1960. This may have been around the time when he started hearing the world differently. It was definitely the moment he became obsessed with finding another father. I had read somewhere that, as a child growing up in San Diego, he couldn't wait to get old, that he'd even pretend to be an old guy, wearing a hat and talking to the neighbours about hi-fi and home insurance. Salvation of a sort came when he discovered Kerouac and Ginsberg in the Sixties, literary hipsters from the previous decade. Until his wife came along two decades later, the Beat writers were his most important influence. He pays homage to them one more time on Orphans, singing Kerouac's forlorn road song 'Home I'll Never Be', and reciting Bukowski's beautiful poem 'Nirvana', both, in their own way, odes to rootlessness, restlessness, the fleeting, irrevocable moment when things could have been different. The essence, in fact, of a good many Tom Waits songs. Why, I ask, were the Beats so crucial to him?

'They were father figures,' he says softly, his long fingers tracing small circles in the coffee spill on the table. 'They were the ones I looked to for guidance. See, my dad left when I was 10, so I was always looking for a dad. It was like, "Are you my dad? Are you my dad? What about you? Are you my dad?" I found a lot of these old salty guys along the way.'

The trains that turn up again and again in his songs also hint at a childhood restlessness, an urge for going that would stay with him until he met the woman he would marry. 'When I was a kid and we went on a car trip,' he says, sounding wistful, 'it seemed like we had to stop and wait for a train to go by every two miles. Seemed like there were train crossings everywhere, nothing but train crossings.'

In adolescence, that restlessness grew profound. Waits left home when he was 15, finding temporary work first as a cook and later as a night-club bouncer. He was constantly on the move, often living out of his car, always writing songs. On the likes of Small Change and Blue Valentine, you can hear the lipstick traces of countless torch singers, as well as echoes of Sinatra's gloriously woebegone album, In the Wee Small Hours. His voice, though, kept fame at bay, and was once memorably described by a reviewer as 'that of a drunken hobo arguing with a deli owner over the price of a bowl of soup'.

As wonderful as many of those early albums are, the act was wearing thin. So, too, was his ambition, his spirit. In 1977, he fell for the singer Rickie Lee Jones(5), whose wayward life echoed his own, and whose most famous song, 'Chuck E's in Love', paid homage to their mutual friend Chuck E Weiss. Waits and Weiss were arrested that same year for disturbing the peace in Duke's Tropicana Coffee Shop(6). His life was unravelling. 'I had a problem,' he says, matter-of-factly. 'An alcohol problem, which a lot of people consider an occupational hazard. My wife saved my life.'(7)

Kathleen Brennan was a scriptwriter whom Waits met in 1978, while just starting out on his other, more fitful career as a character actor. The two first crossed paths on the set of Paradise Alley, a vehicle for the young Sylvester Stallone, with a bit part for Waits, who played a version of himself, a pianist called Mumbles. Brennan and Waits were married in 1980, just a year after he had split with Jones, who would later say, 'What Tom wanted to do was live in a bungalow with screaming kids and spend Saturday nights at the movies.'

There was a lot more to it than that, though. An Illinois farm girl from Irish Catholic stock, Kathleen was the catalyst for the dramatic sea-change in Waits's music that occurred with the release of Swordfishtrombones in 1983. 'I didn't just marry a beautiful woman,' he says, 'I married a record collection.'

The songs he writes with Kathleen are often filled with echoes of older songs. A new song called 'Widow's Grove' begins with a melody borrowed from the old Irish song 'The Rose of Tralee'. He married Kathleen in Tralee. On Orphans, you can also hear traces of John Lee Hooker and John McCormack, the Louvin Brothers and the Clancy Brothers. His record collection, and her's.

'It's all in there,' he smiles. 'Crop failures, dad dying, train wrecks. It all gets handed down, and everything you absorb you're going to secrete. A lot of those old songs stick to you, and others blow right through you, and some of them get trapped in there. You keep hearing them every time you sit down at the piano.'

Kathleen has been his collaborator for almost 25 years now. They have three children, Casey, Kelly and Sullivan, and Casey currently plays drums in his dad's band. When Waits was once asked what his wife brought to the table, he replied, 'Blood and liquor and guilt.' Which is handy, because Waits himself hasn't had a drink for 14 years. When he says that Kathleen saved his life, he means it literally.

'Oh yeah, for sure,' he continues, rocking back and forth again. 'But I had something in me, too. I knew I would not go down the drain, I would not light my hair on fire, I would not put a gun in my mouth. I had something abiding in me that was moving me forward. I was probably drawn to her because I saw that there was a lot of hope there.'

Given that his early songs, his voice and his persona, were drenched in drink, how hard was it for him to give up? 'Oh, you know, it was tough. I went to AA. I'm in the programme. I'm clean and sober. Hooray. But, it was a struggle.'

Does he miss the odd night-cap? 'Miss drinking?' he says, sounding genuinely surprised. 'Nah. Not the way I was drinking. No, I'm happy to be sober. Happy to be alive. I found myself in some places I can't believe I made it out of alive.' That bad, huh? 'Oh yeah. People with guns. People with gunshot wounds. People with heavy drug problems. People who carried guns everywhere they went, always had a gun. You live like that,' he says, without a trace of irony, 'you attract lower company.'

I ask if he wrote a different kind of song when he was drinking. He thinks about this for an instant, then says, 'No. I don't think so. I mean, one is never completely certain when you drink and do drugs whether the spirits that are moving through you are the spirits from the bottle or your own. And, at a certain point, you become afraid of the answer. That's one of the biggest things that keeps people from getting sober, they're afraid to find out that it was the liquor talking all along.'

For a while, Waits had that fear himself, the fear that when he finally dried out the songs would dry up, too. He worked through it, though. 'I was trying to prove something to myself, too,' he says, revealingly. 'It was like, "Am I genuinely eccentric? Or am I just wearing a funny hat?" All the big questions come up when you get sober. "What am I made of? What's left when you drain the pool?"'

Pushing my luck, I ask what was the first album he made when he was clean and serene. It turns out to be a question too far. 'First sober album?' he says, suddenly sounding slightly tetchy. 'Well, if it matters to anybody other than me ...' The sentence trails off and hangs in the air, unfinished. 'I don't know if I want to answer that,' he says finally. 'That's a kind of personal thing.'

Instead, we talk some more about songs and songwriting, the essential mystery of it all. You can tell he respects his gift, nurtures it, and doesn't ever take it for granted; that he has a faith in the song that is almost spiritual. Lately, that faith has started to pay off commercially. His last album, 2004's Real Gone, a rugged affair even by Waits's standards, followed 1999's Mule Variations into the American and British pop charts. Before that, he had only ever dented the mainstream by proxy, when other people covered his songs, most notably Rod Stewart, who took 'Downtown Train' into the Top Ten. The actor Scarlett Johansson has just announced her plan to record an entire album of Waits's songs next year.

As our allotted time runs out, and Waits grows fidgety, we start trading favourite songs, stories, jokes. He has a good one about Barry Manilow and a pair of Siamese twins. Finally, I ask him about 'Fanning Street', a windswept Waitsian ballad from Orphans that has intrigued me since I first heard it, not least because it borrows a title, and maybe even a mood, from an old blues song by the legendary Leadbelly.

'Well, he died the day after I was born - 8 December 1949,' says Waits. 'I always felt like I connected with him somehow. He was going out and I was coming in. And, maybe we passed in the hall. I would love to have seen Leadbelly play, but that's the great thing about records, you put them on and those guys are right there in the room. They're back.'

He picks up his hat and slaps the dust off it.

'I think about that sometimes. Some day I'm gonna be gone and people will be listening to my songs and conjuring me up. In order for that to happen, you gotta put something of yourself in it. Kinda like a time capsule. Or making a voodoo doll. You gotta wrap it with thread, put a rock inside the head, then use two sticks and something from a spider web. You gotta put it all in there to make a song survive.'

I tell him I think he's safe enough on that score. And they'll be lingering in the air long after both of us are gone, the best Tom Waits songs. Like shadows, like ghosts, like echoes.

� Orphans is released by Anti-Records on 20 November

Notes:

(1) Road To Peace: Orphans (Brawlers), 2006. Read lyrics: Road To Peace

(2) Little Amsterdam oyster bar: Further reading: Little Amsterdam

(3) I opened for Frank Zappa, for John Prine...: Further reading: Performances

(4) Ronnie Scott's: London: May 31 - Jun. 12, 1976.

- Ronnie Scott's Club. London/ UK. Waits stays in London for about two weeks and writes most of the songs for his next album: "Small Change".

- "For three nights he sat at the piano, peering out at the empty seats through a haze of smoke from the cigarette cemented to his bottom lip, performing his songs of wry and melancholic beauty. On the fourth night they threw him out. 'I think it was my clothes', Waits says now.".

- Fred Dellar (1976): "There is heckling. "Your opinions are like assholes, buddy," comes the voice from beneath the cap. "Everybody's got one." The fans at the back yell "Shut up!" to the front-line main-mouths. Waits flicks a lighted cigarette into the central area of contention and everybody holds their breath waiting for a fight to start. Nothing happens, so Waits moves on to deliver a finger-poppin' work-out on 'Diamonds on My Windshield' the tempo being about twice that employed on the Heart Of Saturday Night version." (Source: "Tom Waits: Ronnie Scott's London". By Fred Dellar. New Musical Express. June 12, 1976)

- Mick Brown (1981): "The first time Tom Waits visited London, in 1976, he earned the dubious distinction of being thrown out of the club were he had been booked to perform. This was probably nothing new to Waits, who at the time gave the impression of having been thrown out of most places, and - to paraphrase Groucho Marx - of not wanting to join any club that would have him as a member anyway." (Source: "He's A Coppola Swell" by Mick Brown. The Guardian. March, 1981)

- Tom Waits (1987): "That was a tightrope. The rope was round my neck. Nightmares. Playing a lounge in the middle of a golf course with this nomadic audience all waiting for a Moroccan jazz combo. That was a rough gig. Two weeks! Man, I had to dry out after that one. That was like spending two weeks at somebody else's grandmother's house. It was miscasting I was miscast." (Source: "I Just Tell Stories For Money" New Musical Express magazine (UK), by Sean O'Hagan. Date: Travelers Cafe/ Los Angeles. November 14, 1987)

(5) Rickie Lee Jones: Further reading Rickie & Chuck

(6) Disturbing the peace in Duke's Tropicana Coffee Shop: Further reading: Waits And The Cops

(7) My wife saved my life: Further reading: Quotes on Kathleen