|

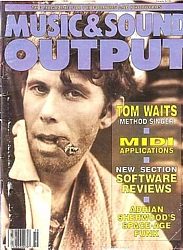

Title: Better Waits Than Ever Source: Music & Sound Output (The Magazine For Performers And Producers)/ (Canada/ USA), by Bill Forman. Vol. 7, No. 11. October, 1987. Thanks to Dorene LaLonde for donating article. Date: Travelers Cafe, Los Angeles. October, 1987 Key words: Frank's Wild Years (album and play), childhood, John Lurie, Jazz influences, studio recording, Farfisa, Innocent When You Dream, bullhorn, Down By Law, Jim Jarmusch Magazine front cover: Music & Sound Output. October, 1987. Photography by: Matthew Rolston/ Outline Press ("Tom Waits in the California Desert, 1987"). Date: 1986/ 1987 |

| Accompanying pictures |

Photography by: Matthew Rolston/ Outline Press. Date 1986/ 1987 Photography by: Matthew Rolston/ Outline Press. Date 1986/ 1987 |

Photography by: Alen Mac Weeney (Island promo picture, ca. 1985). Credits: photography by Alen Mac Weeney Photography by: Alen Mac Weeney (Island promo picture, ca. 1985). Credits: photography by Alen Mac Weeney |

Better Waits Than Ever

by Bill Forman

This story begins with trains. "My father had a friend when he was a kid in Texas, in a place called Sulphur Springs," says Tom Waits, in a corrugated voice custom-built for tales of travel, tears and two-bit hoods. "He was kind of the local James Dean, and he used to race the train to the crossing on an Indian motorcycle. He was always talking about getting out of town. That was his big thing: getting out of town. But he always went to the edge of town and turned around and came back. And whenever the train would go through, it would have to slow down to pick up the mail. They had a hook that would come out and catch the mail sack and then keep going. And one day he was racing the train and he met it right at the crossing, and crashed into it. And he was pinned to the hook." Waits pauses and stares up from the table. "But it did take him all the way to the next town."

Five years after recognizing his need to escape the confines of the fake cocktail jazz aesthetic that first brought him to public attention, Waits has successfully skipped town without the assistance of an impaling mail hook. Still, it was a close call at the crossing. Determined not to continue life as a comfortably eccentric prestige artist made commercially palatable by a succession of producers, Waits entered the studio in 1982 and recorded his first self-produced album, Swordfishtrombones. The glorious result of painstaking reassessment and newfound inspiration, the record defied Elektra/Asylum's expectations. Waits was on his own.

''I was trying to incorporate a lot of musical things that I experienced, but didn't know how to embrace,'' he recalls. ''It's like you start out with a few colors and a certain style and you kind of paint yourself into a comer. I didn't know how to break out, unless I just set fire to it all. And I was afraid to do that, because I didn't know where it would lead me. I thought I would be all alone and I had all these birds in my head and I didn't know how to get them out."

Today, the self-proclaimed Prince of Melancholy(1) has just finished a new album, his third for Island, who also released Swordfishtrombones and its successor Rain Dogs. Frank's Wild Years is a wildly eclectic, uniformly brilliant recording with a truly original sound and vision. First previewed in the song ''Frank's Wild Years" on Swordfishtrombones and later in a play Waits and his wife Kathleen Brennan put on in Chicago(2) , the tale of Frank's quest for fame appears to address the pros and cons of burning one too many bridges, or ranch houses, behind you. The music is loose and unpredictable, like 1985's percussion and guitar-dominated Rain Dogs, though the instrumentation this time out is more heavily slanted toward accordions, an arcane collection of keyboards and a vast array of horns, including the ever-popular police bullhorn.

With a revitalized grip on recording, a burgeoning acting career (Waits starred in Jim Jarmusch's Down By Law, is in Robert Frank's new Candy Mountain and plays opposite Jack Nicholson in the upcoming Ironweed), and his own film venture in the early planning stage, Waits has little incentive to retread old turf these days.

"It's like displacement," he observes over a formidable-looking dish at the Travelers Cafe, an all-but-abandoned Filipino restaurant (pig's head and black beans only $3.89) on the edge of downtown Los Angeles. "As soon as you put something down, something else jumps into your arms. You think that if you don't hang onto this you're going to drown, but you may drown if you do hang onto it. Growth is frightening sometimes. You think you're going to get too big, like you can't get back into your childhood or something."

Childhood is important to Waits, and not only because he now has two kids of his own(3) . "Staying in touch with your childhood becomes more and more difficult, but also more and more important. You can pick up anything and play it - you just have to know what to consider valid and what to consider invalid. When we were doing Down By Law, John Lurie [Waits' co-star who also leads the Lounge Lizards] picked up a big old drain pipe out in the swamp and started blowing through it. And it sounded like a didjeridoo, you know? If you can get yourself to that place where you can attack things like a kid and not be so adult about it, then it opens a window to things."

And, as Waits will tell you, it closes another. "I don't listen to the older stuff. It's like looking at old pictures of yourself. It's like, 'My ears are too big in that one. And, God, the lighting is terrible and I've got a double chin. And, Jesus, look at that shirt. What did I think I was? Who is this guy?' "

Fair question. Tom Waits was born 37 years ago in Pomona, California. Ma Waits was an elementary school teacher, Pa Waits taught Spanish at Belmont high school, only a mile from the Travelers Cafe. Spanish was spoken at the dinner table, Mexican music came over the airwaves and into the Waits household. But Waits' parents weren't inclined toward music, any more than he was toward academics. "Too many teachers in my family," he growls. "Teachers and ministers. I wanted to break windows, smoke cigars and stay up late, you know? My role model was Pinocchio, you know, the little kids that went to Pleasure Island and shot pool. That's what I wanted to do. I wanted to go to Pleasure Island."

Waits' real-life version of Pleasure Island was a long road of run-down hotels, cocktail lounges and restaurants. "I loved working in restaurants most of all(4) ," he deadpans. "Wearing an apron, sitting back there, washing dishes, taking care of things. Feeling like I was in charge." All this eventually led to recording studios and larger venues, which were still workable settings for his collection of small time hoods and restless souls. Like a gambler who repeatedly shows up at the track with no money and last week's racing form, Waits' tales of grand illusions and harsh realities chronicled the failed romantic in all of us, while the gravel-laced voice, dangling cigarette and rumpled clothing personified the dilemma.

A half dozen Elektra/Asylum albums in as many years presented a poignant collection of characters and emotions, fitting documents of the first stage of Waits' career. Small Change gets rained on with his own .38. Tom Frost calls Martha after 40 years to ask about the husband and kids and to confess a still-burning love. And Tom Waits, barely distinguishable from his broken-down characters, sings West Side Story's "Somewhere," the idyllic paradise it conjures up all-too-heartbreakingly out of reach.

Or as Frank puts it in one of the three songs Waits wrote with his wife on the new album, "If I fall asleep in your arms/ please wake me up in my dreams." Pleasure Island still beckons. "I think that's why people make up these little stories, in order to escape into them sometimes," Waits figures. "You become impatient with your fife and so you find these little places where you can kinda move people around and change their names and alter things a bit."

Back when he was working on the score for Francis Ford Coppolla's One From the Heart(5) , Waits met his future wife, which began a stable family life and songwriting partnership, despite a half dozen moves between subletted residences in New York and L.A. over the last few years (L.A. being home for the moment). "I'm beginning to create a world for myself that I can live in," says Waits, defying the belief that creativity dries up when comfort sets in. "Oh, I'm not happy or anything like that," he reassures. "I mean, I'm happy for a minute and then most of us are manic depressive.

"Most of us are a little uneasy around people who are emotionally disturbed, but I think artists have to stay in some state of that in order to remain an antenna for the things necessary to receive from whoever's transmitting. And it makes you a bit of a ... I don't know. And then there are the few that we kind of indulge, people like Salvador Dali. But we don't want too many of those."

Eccentric though they were, Tom Waits' Asylum years were more easily pigeonholed, partly because of arrangements that leaned toward standard jazz combo instrumentation. It was a sound Waits decided to leave behind with Swordfishtrombones. He mourns: "With the exception of a few people -maybe Monk and Mingus, Bud Powell, Miles- a lot of jazz for me conjures up nylon socks and swimming pools and little hurricane lanterns and, you know, clean bathrooms and new suits.

"People want to get you to the point where they know who you are and what you are so they can just kinda bottle it, so you can have one of everything. And it's difficult to grow up in public and be allowed to change and experiment, you know."

As for the orphaned songs from Waits' days with Elektra/Asylum, few will find their way into the live tour he's planning for this fall. "Songs are difficult, because some of them only live for a day. Some of them you just use to prop the door open, and some of them are more of a centerpiece. Each one has its own life. It's hard to tell sometimes how long a song is going to live. You have to go back to them and bring them out and push them around and see if they can take it."

A similar process was called for in the recording of Frank's Wild Years, since the songs first appeared in the context of a stage play of the same name. Waits describes the challenge as "getting them all to walk around in the same shoes," which took some six months in the studio. Sessions began at Chicago's Universal Recording and were completed at L.A.'s Sunset Sound, where Waits also oversaw the remixing -ready for this?- of his first dance single.

While Frank's Wild Years successfully assimilates such obvious influences as Kurt Weill, Marty Robbins and Ennio Morricone (while also paying heed to stray barnyard animals and the Balinese Monkey Chant), the transformation of "Hang On St. Christopher" into a dancefloor hit would be miraculous indeed. Like all of Waits' recording sessions, the remixing was off limits to family members, animals and the press, but Waits seems satisfied with the result, especially the train sound he added. Can't wait to see those dance floor stampedes when the track's muttered vocal, lurching beat, trash can cymbals, Hammond pedal bassline, repetitive horns and twisted modal guitar wanderings segue from the dying beats of Stacey Q.

"I like the stuff that happens in the dance clubs," says Waits. "It's like, free associating, you know, some of these places will blend Filipino folk music with Oscar Lavant(6) and bring in the Dragnet theme and then slip into a Stravinsky thing and then on to Oscar Brown Jr. into James Brown."

Still, a bassline played using the footpedals of a Hammond organ? "I used upright bass for so long, it's hard for me to find an electric bass that I like," he explains. "So that was the closest I could get. It's like a drum with a note in it, you know, real fat and out of focus. Bill Schimmel, the accordion player, played them with his hands. I'm thinking of taking them on the road and raising them to the level of a marimba.

"Things that happened in those sessions were really good. Especially when people were playing instruments they weren't familiar with. I had Ralph Carney, the sax player, on several cuts where he played three saxes at once. And then Bill Schimmel playing the pedals, Greg Cohen playing alto horn... Sometimes approaching an instrument you're unfamiliar with, the discovery process is good."

And then there are those who make familiar instruments unfamiliar, a specialty of borrowed Lounge Lizards guitarist Marc Ribot. "He prepares his guitar with alligator clips," reports Waits, "and has this whole apparatus made out of tin foil and transistors that he kinda sticks on the guitar. Or he wraps the strings with gum, all kinds of things, just to get it to sound real industrial."

Waits had his own arsenal of prehistoric keyboards, the type you don't find on records these days. There's his wheezing pump organ, his plodding Mellotron, his tacky Farfisa and, of course, the Optigon(7) . "The Optigon is kind of an early synthesizer/ organ for home use. You have these discs that give you different environments -Tahitian, orchestral, lounge- and then you apply your own melodies to those different musical worlds. It comes with a whole encyclopedia of music worlds.

"I've always liked the Mellotron(7) as well. The Beatles used it a lot, Beefheart used it a lot. They're real old and they're not making them anymore. A lot of them pick up radio stations, CB calls, television signals and airline transmitting conversations. And they're very hard to work with in the studio because they're unsophisticated electronically. So it's almost like a wireless or a crystal set."

Waits' unconventional approach to recording doesn't end with his choice of instruments. "Telephone Call from Istanbul" goes rollicking along with banjo, guitar, bass, drums and the faint ghost of Waits improvising away on that cheesy Farfisa. When the track is nearly over, the Farfisa kicks in full strength, catapulting the listener into some hellish Turkish rollerskating rink. "I usually don't like to isolate the instruments," says Waits, explaining the appearance of the ghost early in the track. "On that song, I pulled out the Farfisa and then just put it in very hot at the end, just so it sounded kind of Cuban or something."

Likening the sterile confines of the studio to an emergency ward, Waits seems intent on performing some very unorthodox operations. Take "Innocent When You Dream," which appears in two disguises on Frank's Wild Years. The "barroom version" puts across the melancholy melody (reminiscent of a mournful Irish drinking song) by way of pump organ, upright bass, violin and piano. A second version closes out side two, stripped down and scratched up enough to inspire visions of an ancient Victrola. Says Waits: "The '78 version' of that was originally recorded at home on a little cassette player ["the Tascam 244, the one with the clamshell holster"]. I sang into a seven-dollar microphone and saved the tape. Then I transferred that to 24-track and overdubbed Larry Taylor on upright, and then we mastered that. Texture is real important to me; it's like attaining grain or putting it a little out of focus. I don't like cleanliness. I like surface noise. It kind of becomes the glue of what you're doing sometimes."

Another innovation on Frank's Wild Years is the prevalence of the bullhorn, which Waits sings through on at least four cuts. "Well, I tried to obtain that same sound in other ways," he explains, "by using broken microphones, singing into tin cans, cupping my hands around the microphone, putting the vocal through an Auratone speaker, which is like a car radio speaker, and then miking that. Practically even considered at one point making a record and then broadcasting the record through like a radio station and then having it come out of the car and then mike the car ... and then it just became too complicated, you know? So a bullhorn seemed to be the answer to it all."

Waits says obtaining altered sounds in real time, rather than creating them afterwards through studio gadgetry, allows him to react to the effect and modify his vocal delivery accordingly. "Plus it makes me feel like I'm making the sound rather than finding the sound through EQ and whatever. I feel more like I'm building some kind of a little world for myself, my own territory.

"I used to just write songs and think that was enough. I used to be frightened of the studio. But there's a lot you can do if you don't allow it to intimidate you. It's a laboratory, whatever you bring into it you have to know what you want to do with it. I worked with a lot of good people that helped me. Victor Feldman(8) , the percussionist who just passed away a few months ago, helped me a lot with instruments. I kinda wanted to get away from the standard fare and experiment with some other instruments- Balinese instruments and things like that, boobams and onwongs and African drums, that type of thing. So he helped me a lot.

"I try to stay open to as many choices as I can," he continues. "It can be 13 bass players, it can be recorded outside, it can be done in the bathroom. There's a lot of ways to skin a cat. Being in the studio is like organizing noise. I just had to learn how to know exactly what I wanted and not be satisfied until I heard it. It's a journey, it's like being a scavenger.

The artist describes himself as an "idiot savant" when it comes to things technical. "I'm still very -I don't know- primitive in the studio. It's not a science and I don't approach it that way. And I don't necessarily have a way of working now that I bring with me every time I record. Mainly I try to keep things spontaneous and live, full of suggestions. Keep it living."

Asked how he directs his musicians in the studio, Waits says, "You just have to develop a way of communicating. Just like a director talks to an actor, you have to know how to say the right thing at the right time to the right person that will have meaning to them. It's like calling a dog -what do you say? You whistle, you slap your thigh, 'C'mere, boy! ' "

Waits laughs at his analogy." That's terrible. No, it's not like that. Sorry, boys."

Lyrically, Frank's Wild Years is a no less extravagant puzzle, from the good advice of "Telephone Call From Istanbul" (Never trust a man in a blue trench coat/ Never drive a car when you're dead) to the poignant assessment of "Yesterday Is Here" (Today is grey skies/ tomorrow's tears/ You'll have to wait til yesterday is here).

The LP essentially takes up where the song of the same name left off. Frank has already burnt his suburban home to the ground while parked across the street drinking a couple of Mickey's Big Mouths. Now it's on to a series of less-than-glorious adventures that leave him on a park bench in the middle of a snowstorm.

"Well, it opens on a park bench in the play," says Waits," with a guy who is having a going-out-of-business sale for his life. And he lays down on the bench and its 30 below in East St. Louis and he kind of dreams his way back home, and that's where he relives everything that happened. So it's kinda putting the end of your life first and the beginning of your life second.

"It's really a simple story of a guy who is very near suicide, who has been allowed to kind of walk back through his life before he goes under. And he has a chance to turn the ship around, set a new course for himself. That's really all it's about.

"It just represents somebody who decided to make a change in his life, and in order to do that you have to cut some of the strings that are holding you there, that's all. And then he came back looking for some answers, because the road that he took led him down some very dark paths. So he came home to kind of purge himself and confess and look for some reasons to keep going. It's like going through your past looking for answers, that's all."

But Waits discourages biographical interpretations. "Usually you hide what everything represents," says the songwriter. "You're the only one who really knows. I don't so much chronicle things that happen to me as kind of break down the world and dismantle it and rebuild it and look at it that way. Pieces from a lot of different places.

"On this album, I've learned to try to approach each song like a character in a little one-act play. I don't feel like I have to be the same guy in all the songs. So in each one I set the stage for myself and I try to approach it in whatever way I have to in order to be living in the story. You know, method singing''

The method singer's acting career also continues to develop through a series of bit parts that culminated in last year's starring role as Zach, the melancholic DJ in Down By Law.(9) "I was real nervous about doing that at first," he recalls. "I wanted to back out." But once Waits went on location in Louisiana, he became more confident. "Mostly I just tried to relax and be natural. As far as developing a detailed character filled with all the geography of the imagination, I don't think I covered a real deep tree. But I had never really done anything that intensive. Most of the parts I had were just a couple of lines."

Director Jarmusch, who saw the Chicago Steppenwolf Theater Company's production of Frank's Wild Years three times, praises Waits' acting abilities and adds that Waits helped develop the part of Zach, originally written into the script as a musician. "Zach's very sullen and doesn't want to talk, and yet as a DJ he's someone who talks for a living," says Jarmusch. "And I think that's sort of about Tom too, in a way. Personally, he's contradictory in certain ways. Tom can have a hot temper, he can be kind of tough, but there's something very gentle at the same time. He's very tough and very gentle at the same time. He doesn't, really stop between those two poles, "He's always sort of shifting back and forth between them. it makes me like him a lot."

In Ironweed, Waits plays Jack Nicholson's sidekick Rudy, a smalltime hood (naturally), who dies in the end. "Nicholson's a great American storyteller," enthuses Waits. "When he tells a story, it's like a guy soloing, he's out, you know? Very spontaneous, thinks on his feet. I remember he said, 'I know about three things: I know about beauty parlors, movies and train yards,' "

For Waits, beauty parlors are still something of a mystery. But he is planning his own film project(10) . "It's scattered now, maybe it's too early to talk about it," says Waits, giving in with little prodding. "It's about a bailbondsman who has amnesia on this journey into the city with a kid who doesn't read or write. It's kinda like a blind seeing-eye dog. You know, with music, narration, voice over, kinda Brechtian, you know?"

And what would the look of the film be? "Kind of like Eraserhead."

There's more. An upcoming promotional video for Frank's Wild Years(11) will cast Waits as a ventriloquist using a fat lady for his dummy. He also plans to contribute music for a country & western opera by Robert Wilson(12) . "He said there'll be like seven principal players and all the rest will be carrying spears, " recalls Tom. "It's a little oblique."

Waits also expects to contribute a spoken-word piece, excerpted from Charles Mingus' autobiography, to an upcoming album project of Mingus interpretations(13) being compiled by producer Hal Willner. And he's also starting a new collection of songs with the working title, "Nothing But Trains."

But don't expect '78 versions' of any of these new songs, for Waits' Tascarn four-track is gone, clamshell holster and all. "Stolen in New York," he shakes his head, suppressing a smile. "That's why I left - they beat me up. So now I'm back to square one. I don't know, I'm just learning about sound relationships and how the circumstances under which you record something always color the work. You do it at home, you're in a different mood than you are in the studio.

"It's like acting. There are certain relaxation techniques to get yourself to tap into your unconscious. You know, it's like they say, certain things transcend culture and countries: insanity, animals and music."

And exactly who says that?

Waits pauses before answering in a low voice.

"I don't know, uh... I said it."

Notes:

(1) Prince of Melancholy: Nickname given to Waits on the set of Down By Law (1985).

- Tom Waits (1987): 'It was Dr Sullen [Waits' name for Jarmusch], Bob Angeles [Benigni], the Great Complainer [Lurie], and I'm the Prince of Melancholy." (Source: "Son Of A Gun, We'll Have Big Fun On The Radar" New Musical Express magazine (UK), by Bill Foreman. Date: January 10, 1987)

(2) A play Waits and his wife Kathleen Brennan put on in Chicago: Further reading: Franks Wild Years

(3) Two kids of his own: Daughter "Kellesimone": September, 1983 (some sources claim the right date to be October, 1983), son "Casey Xavier": October 24, 1985 (some sources claim the right date to be September, 1985)

(4) I loved working in restaurants most of all: further reading: Napoleone Pizza House

(5) Francis Ford Coppolla's One From the Heart: further reading; One From The Heart

(6) Oscar Lavant: "Oscar Levant (born December 27, 1906 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania - died August 14, 1972) was a pianist and an actor, better known for his character than his music. In 1928 Levant traveled to Hollywood where his career turned for the better. During his stay, he met and befriended George Gershwin. Around 1932 Levant began composing on a serious note. During the years of 1958 and 1960, Oscar Levant syndicated his own talk show, The Oscar Levant Show. The show was highly controversial, finally being taken from the air after a comment in regards to Marilyn Monroe; 'Now that Marilyn Monroe is kosher, Arthur Miller can eat her.' He later refuted he "hadn't meant it THAT way." Several months later, the show was rebroadcasted in a slightly revised format. The show was now taped to use as a buffer to Oscar's antics. This however, failed to prevent Oscar from making some comments of Mae West's sex life, cancelling the show for good. Oscar Levant drew increasingly away from "starlight" in his later years. On his passing in 1972 he was interred in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles, California."

(7) The Optigon/ Mellotron:

- Should be spelled "Optigan": The Optigan was a kind of home organ made by the Optigan Corporation (a subsidiary of Mattel) in the early 70's. It was set up like most home organs of the period - a small keyboard with buttons on the left for various chords, accompaniments and rhythms. At the time, all organs produced their sounds electrically or electronically with tubes or transistors. The Optigan was different in that its sounds were read off of LP sized celluloid discs which contained the graphic waveforms of real instruments. These recordings were encoded in concentric looping rings using the same technology as film soundtracks. As the film runs, a light is projected through the soundtrack and is picked up on the other side by a photoreceptor. The word "Optigan" stands for "Optical Organ". Some Optigan Disc Titles Banjo Sing-Along, Big Band Beat, Bluegrass Banjo, Bossa Nova Style, Cha Cha Cha!, Dixieland Strut, Folk & Other Moods-Guitar, Gay 90's Waltz (6/8 time), Gospel Rock, Guitar Boogie, Guitar in 3/4 Time, Hear and Now, Latin Fever, Nashville Country, Polynesian Village, Pop Piano Plus Guitar, Rock and Rhythm, The Blues-Sweet and Low, Waltz Time (3/4 Time). Further reading: Instruments

- Mellotrons (and Novatrons) were produced in England by Streetly Electronics from the early '60s until the early '80 by Leslie Bradley and his brothers Frank and Norman. The original Mellotron was designed as an expensive domestic novelty instrument. The Mellotron was a precursor of the modern digital sampler. Under each key was a strip of magnetic tape with a recorded sound that corresponded to the pitch of the key (The Mark II had two keyboards of 35 notes each making a total of 1260 seperate recordings). The instrument plays the sound when the key is pressed and returns the tape head to the begining of the tape when the key is released. This design enables the recorded sound to keep the individual characteristics of a sustained note (rather than a repeated loop) but had a limited duration per note, usually eight seconds. Most Mellotrons had 3 track 3/8" tapes, the different tracks being selectable by moving the tape heads across the tape strips from the front panel. This feature allowed the sound to be easily changed while playing and made it possible to set the heads in between tracks to blend the sounds. Despite attempting to faithfully recreate the sound of an instrument the Mellotron had a distinct sound of its own that became fashionable amongst rock musicians during the 1960's and 1970's. The Novatron was a later model of the Mellotron re-named after the original company liquidised in 1977. Further reading: Instruments

(8) Victor Feldman: - The album 'Heartattack And Vine'. Album released: September, 1980. Chimes , percussion ("Saving All My Love For You"), keyboard glock and percussion ("Jersey Girl"); - The album 'One From The Heart'. Album released: early 1982. Tymps ("You Can't Unring A Bell"); - The album 'Swordfishtrombones'. Album released: September, 1983. Bass marimba, marimba, shaker ("Shore Leave"), bass drum with rice ("Shore Leave"), brake drum ("16 Shells From A Thirty-Ought Six"), bell plate ("16 Shells From A Thirty-Ought Six"), snare ("16 Shells From A Thirty-Ought Six"), Hammond B-3 organ, bells, conga, Dabuki drum, tambourine, African talking drum; Further reading: Who's Who?

(9) Zach, the melancholic DJ in Down By Law: Down by Law (1986) Movie directed by Jim Jarmusch. Shot on location in New Orleans in 1985. TW: actor & composer. Plays main role as DJ Zack. On soundtrack: "Jockey Full Of Bourbon" and "Tango Till They're Sore".

(10) But he is planning his own film project: Waits hinting at the upcoming concert film "Big Time". Further reading: Big Time

(11) Promotional video for Frank's Wild Years: "Blow Wind Blow" (1987) Music video promoting: "Blow, Wind Blow" (Island, ca. August, 1987). With Val Diamond. Directed by Chris Blum. Shot at The Chi Chi Club run by former "exotic dancer" Miss Keiko, on 438 Broadway in San Francisco.

- Tom Waits (1987): "Kathleen and I put together the ideas for it. It was done up there at the Chi Chi Club ... in [San Francisco's] North Beach. Miss Keiko's Chi Chi Club right there on Broadway next to Big Al's. I worked with a girl named Val Diamond, who played a doll. She drew eyeballs on the outside of her eyelids and wore a Spanish dress and I unscrewed one of her legs and pulled a bottle out of it. It's got some entertainment value." (Source: "Morning Becomes Eclectic": KCRW-FM, Deirdre O' Donohue. August, 1987)

(12) A country & western opera by Robert Wilson: Waits hinting at the upcoming collaboration on the play "The Black Rider". Further reading: The Black Rider

(13) An upcoming album project of Mingus interpretations: this project actually never happened