|

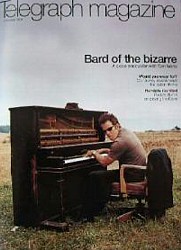

Title: Bard Of The Bizarre Source: Telegraph Magazine (UK). By Richard Grant. Transcription by Jarlath Golding as sent to RaindogsToo Listserv discussionlist. October 4, 2004 Date: Little Amsterdam restaurant, Petaluma CA. July/ August. Published: October 2, 2004 Keywords: Real Gone, Little Amsterdam, smoking, Robert Crumb, Kathleen, midget orchestra Magazine front cover: Photography unknown |

| Accompanying pictures |

Bard Of The Bizarre

Trailer-park troubadour Tom Waits, the silver tongued songwriter with a thing about midgets and one-eyed men, does not like a direct question. Ask him about his family and he'll tell you what women use for hair mousse in prison.

By Richard Grant

Moonlight, trains, whiskey, killers, circus-freaks, deformed lounge singers, preachers waving guns around, alligator shoes: we are entering the songlands of Tom Waits. The sun won't shine and there is an extraordinary proliferation of midgets and one-eyed men. People have names like Bow-Legged Sal and Burnt-Face Jake and they use old trombones to fix the toilet and they hammer rings into bullets and make tattoo guns from cassette motors and guitar strings. Call it Waitsland. He has staked out this surreal, archaic American territory as his own and given it an utterly distinctive sound - gruffly romantic, beautifully written ballads interspersed with a weird, fractured, clanging music of his own invention. Waits is an aficionado of obscure instruments (pump organs, Mellotrons, the 'basstarda')(1)and his percussion often sounds like it was played on a marimba made of bones and scrap metal, or hammered out with a fist on an old chest of drawers. Then there is the unmistakable voice: a rumbling, rasping, tubercular growl, capable of conveying wistful tenderness, barking lunacy and deadpan humour with equal facility.

For many years Tom Waits was a cult figure with modest sales, but his 1999 album Mule Variations went into the top 10 in Britain and sold a million copies worldwide. Now, at the age of 54, he is widely regarded as one of America's greatest living songwriters and performers, and reputed to be something of an eccentric recluse.

I find him in an impeccably Waitsian establishment not far from his home in the rolling hills of northern California. The Little Amsterdam(2) is a ramshackle roadside bar and restaurant with a miniature windmill out front, a trailerpark out back and an old piano under a tarpaulin by the side entrance. The owner is a retired Dutch sailor with a deep passion for Mexican bullfighting, and inside the walls are covered with bullfighting posters, sweat-stained sombreros and bulls' ears attached with spiked daggers. And there in a black vinyl booth, next to an albino catfish in a tank, Tom Waits is sitting with a cup of coffee and inhaling deeply from an empty pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes. 'Ah yeah, I'd like to strap this on like a goddamn feedbag,' he growls, huffing and snuffing and emitting deep, pining groans of pleasure. 'Take a whiff, go ahead, yeah yeah yeah... Hey don't take all the smell.'

Cigarettes played a major part in the curing of Tom Waits's voice and they were once an integral part of his persona. When he started out in the music industry as a young man in the 1970s he cast himself as a barfly troubadour, sitting at the piano with a drink and an overflowing ashtray and singing sad, witty, closely observed songs about America's misfits and low-lifes. He dressed in shabby beatnik suits, shaved infrequently, read a lot of Kerouac and Bukowski, took up permanent residence in a room at the sleazy Tropicana motel in Hollywood(3), moved a piano inside it, developed a deep and troubled relationship with the bottle and was seldom seen on an album cover without a cigarette. That was the first phase of Tom Waits's career and the turning point came in 1980 when he met his wife Kathleen Brennan.

He had been commissioned by Francis Ford Coppola to write the songs for a musical called One From The Heart(4) ; she was a script editor at Coppola's studio. They fell in love, married soon afterwards and started having children, ending up with two boys and a girl. Waits moderated his drinking successfully and by all accounts gave up smoking more than 20 years ago. So why is he snuffling so excitedly at an empty packet of Luckies?

'Jim Jarmusch,' he says with a low, rumbling sigh, referring to the independent film director. 'He put me in his new movie Coffee and Cigarettes(5). It's me and Iggy Pop and basically what we had to do was sit around and drink coffee and smoke cigarettes. I started again. Got hooked. Terrible. But hey, it takes a man, right? It takes a real man to quit twice.'

He looks uncharacteristically tanned and healthy with muscled arms in a short-sleeved, tight-fitting shirt, with ink stains over the pocket, worn with black jeans and battered motorcycle boots. His curly mop is dyed auburn, and white chest hair sprouts from the top of his shirt. The eyes are smallish, deep-set, clear blue and hard to read. He leans on his elbow as he talks and cups his jaw with silver rings on his long, bony fingers, and his voice is even deeper and more heavily laden with gravel than you expect from the records. It seems in danger of descending below human frequencies.

His new album, Real Gone, with its bellowing roars and extraordinary braying noises, was punishing on the vocal chords and that's the way he likes it. 'Oh yeah, I get all banged up in the studio. At the end of the day I want to feel like I've been to work. You have cuts on your hands, you don't know where they came from. You're bruised up and sweating. I love it.'

On some of the songs, in search of a new sound that he identifies as 'cubist funk', he replaced the drums with his own vocal effects. 'Mouth rhythm is what I call it. It's old. Pygmies do it. You ever hear any of that stuff? Sounds like birds and hogs. Amazing. They also do this thing where two people go into the water and they play the water. Kla-boom-splash, just the sound of your hand slapping the water and going in but all very rhythmic and controlled. Then of course the Romiyiana Monkey Chant, oh man, those guys. Chacka-chacka-chack-chack-cha... But it's like a thousand men sitting in concentric circles in Bali, telling a story about when all these monkeys came out of the trees and saved the tribe and they offer up this chant as a way of thanking the monkeys. It's a wild, wild piece of music. It'll scare the kids.'

What else has he been listening to? 'Underground hip-hop. That's my son Casey's music but it's in the house. It all gets mixed up. Records from Barcelona, flamenco cross-breeding, Arabic mariachi. I don't know.'

How are things at home? How would he describe the basic dynamics of his family? He clears his throat with a sound like a pneumatic drill and clomps over to the coffee pot with a loop of underwear caught up in his belt. He sits back down and says. 'Do you know what the girls use for hair mousse in jail?. They use Jolly Ranchers (a popular brand of boiled sweet). They melt it in a spoon and slick back their hair with it. Sets solid and tastes good.'

He is happy to talk about music and the world and display his gifts as a raconteur, tall-story teller and laconic wit, but he blocks and dodges all inquiries into his personal life and family. He has a range of techniques for doing this: the disgusted look, the string of increasingly obscure metaphors, the shaggy-dog story that proceeds from the question at hand but never returns to it and the abrupt non sequitur into a strange and amazing fact of dubious veracity. What you get is a persona, an entertaining and diversionary performance from a master showman. When I ask him how much of a private self is in that persona, he looks at me as though I've crapped on a plate and pushed it towards him. 'Fuck that. I hate direct questions.'

I ask about his parents, and he tells me a dream he had recently. 'I was on the back of a motorcycle and my dad was driving and we were going straight up the trunk of a tree. He had some special little hook device that he would throw up over a branch to increase out pull. I'm hanging on as best I can and finally I realise that we're gonna fall back on our backs, like a horse. And just at that moment I let go in terror and find that I'm only a foot off the ground.'

Over the years Tom Waits has told a dozen stories about his origins. For instance: 'I was born in the back seat of a Yellow Cab in a hospital loading zone and the meter running. I emerged needing a shave and shouted, 'Times Square and step on it.''

The records indicate that he was born and raised in the suburbs of Los Angeles(6), that his father was not an accordionist, funeral director or midget circus performer, but a high-school Spanish teacher. His parents divorced when he was 10. Tom went with his mother to San Diego, left home at 15, lived in his car, found work as a cook and later as a nightclub doorman(7) . He started writing and performing songs on the piano and the guitar about the demi-monde nightlife he was encountering, signed his first recording contract at the age of 21 and has worked ever since in 'this business we call show' as he mockingly puts it.

He has released more than 20 albums, written or co-written 5 musical plays, received an Oscar nomination for his One From The Heart score and contributed songs to many other films, including Dead Man Walking, Big Bad Love, Liberty Heights, Pollock and Shrek 2. He has also appeared as an actor in more than a dozen films, with major roles as a luckless radio DJ in Jim Jarmusch's Down By Law, an alcoholic limousine driver in Robert Altman's Short Cuts, a pickled hobo in Ironweed, a lunatic valet in Bram Stokers Dracula and as himself in Coffee and Cigarettes. He has great presence on the screen, but all his characters are variations on the same theme, a truth he happily acknowledges. 'I used to have it right there as a clause in my acting contracts: Let Waits be Waits. If they comply with my conditions, I do ok. You might say I'm limited as an actor and right now I'm not interested in doing any more of it. I don't want to be away from home that much.'

He lives on an old farm in the hills of Napa County, with Brennan, Casey Xavier, 18, Kelly Simone, 20, and Sullivan, 11. I ask him if he gets out much and who his friends are. 'I get out enough for me; I come here and see the Mexican bands. Do you remember that scene in Crumb (the documentary about the cartoonist Robert Crumb) where he's sitting at the piano and he looks like a giant and the piano looks like a shoebox? And he's hunched over it like he lives in a dollhouse, like if he stood up, the chimney would fall over and there'd be a big hole in the roof and his head'd be sticking up out of it. Great scene, just the way they shot that.'

I'm accustomed to his strategies by now and move right along. Does he repair his own fences and barns or build weird mechanical contraptions like the characters in his songs? 'My talents rarely come in handy for that sort of thing. The question around my house is always 'Who's going to replace that broken window? Who's going to fix the sink?' If this was The Flight of The Phoenix (the Jimmy Stewart film) and our plane crashed in the middle of the dessert and we had to make it fly again, I might be able to successfully compose a ballad about the events once they were over, but during our struggle I would be radically useless.'

The biggest mystery about his life is the role of Brennan. She has never given an interview and no photograph of her has been published since 1980, as far as I can determine, and Waits will only talk about her influence in vague terms. 'If it wasn't for her, I'd be playing in a steakhouse somewhere. No, I'd probably be cleaning the steakhouse.'

Normally, when musicians sober up, settle down, marry and have kids, their music gets safer and more complacent. Precisely the opposite happened with Tom Waits. The more conventional his home life, the more outlandish, demented and experimental his music became, and this was largely Brennan's doing, he says, 'She encouraged me to look at songs through a funhouse mirror and then take a hammer to them and now we do it all together, like a family business.'

She is credited as co-writer and producer on nearly all his music now and I ask him how the collaboration works. 'Well, it's like setting off firecrackers. You get to hold the firecracker and I get to light the fuse and throw it.' The songs sound very masculine, I say, or is she into whiskey and guns as well? He chuckles and impersonates his wife.: 'Do you have to put a one-eyed guy in every tune? Why do you have to put a midget in every song? ' Then feigns his reply: 'I don't know baby. Ok, we'll give him back his eye. We'll make him a little taller. There, you feel better now?' Who has the original ideas for the songs? 'The songs are out there but you have to sneak up on them if you're gonna catch them alive. Other songs just come out of you, like you're talking in tongues. It's like 'wop-bop-alooba-a wop-bam boom'. Where did that come from? Incantation. It has great power and it scares the hell out of a lot of people, especially coming from a little black man with real high hair who looks a little effeminate and has a high voice and bug eyes and is completely out of his mind.'

Real Gone was largely recorded on four-track tape in the farmhouse bathroom. He liked the acoustics of the room, the way it made his mouth rhythms reverberate, and then he started moving instruments in there. His intention was to recreate the bathroom tapes with a band in the studio but the acoustics weren't as good and the musicians ended up playing over the original bathroom tapes. Much of the album has a raw, primitive, slightly chaotic sound, stripped down to the bones with odd pieces of meat still hanging off them. 'Did you ever listen to an orchestra tuning up? It's not supposed to be music yet and someones doing scales, someone's going over a passage they keep tripping on; it's sort of like bees, you know it's scary. Sometimes I leave right after that. Kidding of course, but in my mind I've left because now it's combed and groomed and bland and systematic and organised and they've lost the spontaneity. For a while there, before they began the piece, they were all like a wild hairdo and they had no idea how great that was. That's what we're shooting for and it's always to the left of where you're aiming, like photographing ghosts.'

The album also contains some hauntingly beautiful ballads, including Day After Tomorrow, a letter home from a teenage soldier in what is clearly Iraq, and Waits's first ever political song(8). 'The government looks at these 18-year-old kids as shell casings, you know, like we're getting low on ammo, send in some more. We're neck deep in the big muddy and the big chief is telling us to push on and offer up our children. I sure wouldn't want to let my boys go.'

There are other new explorations - an Afro-Cuban pirate song, a punk mambo - but more than anything Real Gone sounds like another first-rate Tom Waits album. The classic one-liners are there - 'My baby's so fine, even her car looks good from behind' - and so is the obligatory spoken-word track. Over a broken carousel waltz, he growls out a portrait of a struggling family circus featuring Horse-Face Ethel and her Marvellous Pigs in Satin, and One-Eyed Myra the animal trainer: 'She looked at me squinty with her one good eye in a Roy Orbison T-shirt as she bottle fed an orang-utan named Tripod...'

What is it with Waits and mutant circus performers? 'That old time circus, carnival, freakshow world just fascinates me. I mean Johnny Eck(9), you know the stories about him? He was the man born without a body, meaning his body really stopped at the top of his legs. He had his own orchestra and he was a pianist and he had a twin brother who was of normal stature. And they had an act in vaudeville to saw a man in half. Johnny Eck would sit in the box and they would have the wooden legs with shoes on and the whole thing. They sawed Johnny in half, you know. Afterwards he would get up out of the box and he would walk off stage on his hands. They had to have medical people on staff at the theatre because people were so overcome. It was before television, you know, and movies were really tame.'

This is a true and verifiable story but I can't vouch for all the particulars of the next one. 'I put together this midget orchestra a while back. I met this guy Angelo who was two and a half feet tall, was in Bela Lugosi movies, wonderful man, in his seventies, and he played the accordion. I had a guy on marimba, a percussionist, a trombone player, two clarinets, a guitar. It was all these guys I met through Angelo and Billy Hardy, who ran the Little People's Association of America and was in North Hollywood in a long building, and way at the end of it was a desk and he sat behind that desk with a cigar that was, like, 14in long. And he was 100 per cent on my side: 'I love it Tom, I love it....'In the end I have to say it kinda fizzled . I got nervous about being, you know, politically correct. I'm a normal sized person and I've got all these little people on the stage with me. They all loved it but I got nervous. I had all these messages on my machine.'He puts on a high-pitched voice 'Hey Tom, what's going on with the band?....' 'Hey Tom, it's Joe down here in Orange County. When's the rehearsal , I'm waiting, I'm waiting....'I felt really bad and called them all back and said, 'Didn't work out guys.'' He checks his watch. Our time is up. We walk outside and stand between the miniature windmill and his big, black, muddy Chevy Suburban and he points up at the grassy hills across the road. 'Kids around here sled down those hills on pieces of cardboard. Me, I'd like to get a cardboard suit - thin lapels, you know, pegged pants, something sharp - and come down that sucker in style.' He points down the road with his chin. 'Well I've gotta go fix the sink and get the dog out of the fireplace.'

Notes:

(1) Pump organs, Mellotrons, the 'basstarda': further reading: Instruments

(2) Little Amsterdam: further reading: Little Amsterdam

(3) Tropicana motel in Hollywood: further reading: Tropicana full story

(4) One From The Heart: further reading: One From The Heart full story

(5) Coffee and Cigarettes: Coffee and Cigarettes (1993). Movie directed by Jim Jarmusch. TW: actor (conversation with Iggy Pop as himself). "Coffee and Cigarettes" DVD released on September 21, 2004.

- Jim Jarmusch: "Tom was exhausted. We had just shot a video the day before for "I Don't Wanna Grow Up" and he had been doing a lot of press. He was kind of in a surly mood as he is sometimes, but he's also very warm. He came in late that morning - I had given him the script the night before - and I was with Iggy. Tom threw the script down on the table and said, "Well, you know, you said this was going to be funny, Jim. Maybe you better just circle the jokes 'cause I don't see them". He looked at poor Iggy and said, "What do you think Iggy?" Iggy said, "I think I'm gonna go get some coffee and let you guys talk." So I calmed Tom down. I knew it was just early in the morning and Tom was in a bad mood. His attitude changed completely, but I wanted him to keep some of that paranoid surliness in the script. We worked with that and kept it in his character. If he had been in a really good mood, I don't think the film would have been as funny." (Source: "Jim Jarmusch". Village Noize, 1994 by Danny Plotnick)

- Coffee and Cigarettes shown at (2004) opening night of the 47th San Francisco International Film Festival. "The movie -- a series of oddball conversations around various tables -- may not be everyone's cup of tea. But Thursday evening's crowd appreciated its dark humor, a trademark of director Jim Jarmusch, who told the audience this was his film's U.S. premiere. "We did show it at the Toronto festival, but that's a whole different country, and their leaders aren't on a death trip." Somehow, I don't think he was referring to closet smokers in the Bush administration. Waits and Pop had quit smoking before Jarmusch cast them, but he made them start again. "They were really mad about it, too," he said. All must be forgiven because Waits stood beside him onstage, along with the Wu-Tang Clan's the RZA... Following the screening, everybody repaired to the Galleria to party. Waits was spotted patiently waiting in line until it was pointed out that he could use the VIP entrance." (Source: "Java, smokes, stars in Jarmusch opener at festival" San Francisco Chronicle. Ruthe Stein. April 17, 2004). Further reading: coffeeandcigarettesmovie.com

(6) He was born and raised in the suburbs of Los Angeles: It is generally assumed Waits was born December 7, 1949 in Whittier Pomona at Park Avenue Hospital.

(7) Found work as a cook and later as a nightclub doorman: further reading: Napoleone Pizza House, The Heritage

(8) Waits's first ever political song: and indeed it is. It's extremely remarkable Waits decided to release this song. For reasons unknown, Waits never ever made political statements in his songs before

(9) Johnny Eck: further reading: "Lucky Day Overture", "Table Top Joe"