|

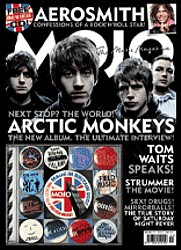

Title: What's He Building In There? Source: Mojo magazine (USA/ UK) issue 162 May 2007, by Sylvie Simmons. Transcription by Jarlath Golding. Further reading: Sylvie Simmons official site Date: September 2006, published April 4, 2007 Key words: Early years, Kathleen, childhood, songwriting, Harry Partch, Victor Feldman, Emil Richards, recording, Alan Lomax, commercials Magazine front cover: Mojo magazine, issue 162, April/ May 2007 |

What's He Building In There?

Just where does Tom Waits, master songwriter and alchemist of sound, get all his ideas from? Eager to find out, Sylvie Simmons sat down for a master class with the sawbones of strange and tried to capture some lighting in a bottle.

It was Tom Waits' idea to meet in a roadhouse(1). Not just any roadhouse but the oldest in California, a former whorehouse built of wood and painted raw-steak red. It boasts a restaurant with no one in it - the folks out here in rural northern California being the sort who eat out only on a weekend - and a bar whose ceiling is covered with business cards pinned to dollar bills. There's a jukebox that seems to have been stocked by John Fogerty and a sloping wooden floor.

"I like floors that are a little tilted," says Waits, who has just walked in, "because I have vertigo, and I think it corrects it." Dressed in denim and black, looking lean and scrappy, in one hand he holds a large notebook, in the other a brown paper bag.

Waits likes roadhouses. He particularly likes that they're "right off the road and you can park by the door". It's the same when he stays in a motel. "I want a ground floor room or I'm not interested. It's just wanting to feel that you can just jump on your horse and go." Choosing a perfect quick getaway table overlooking the parking lot, he hands MOJO the paper bag. It contains home-grown tomatoes. Heirlooms, they're called, big and gnarly-looking, from Waits' garden. He puts the notebook on the table in front of him. It contains weird facts, fleeting thoughts, things he's read in newspapers, scraps of overheard conversation and titles for potential songs. "If it's enough of a seed I'll save it and plant it later," he says horticulturally. Since giving up drinking for gardening, there are frequent flora metaphors in his conversation." What I do is kind of abstract. I don't work on cars, I work on things that are, in some way, invisible."

Waits is a master songwriter who likes to pretend he's a bin raider, not so much composing his demented nerve-jangles and sentimental broken beauties as welding together a bunch of found sounds with some new ideas, cobbled-together instruments with traditional ones, speaking with singing and mouth-rhythms that sound like both field recordings and computer loops. His creations have become even more experimental with age; he's 56 years old and definitely looks likes he's lived every one of them. His manner, though, is youthfully restless and curious, his eyes sharp and alert.

"Well, the only reason to write new songs is because you're tired of the old ones, that's really all it is. Or I'm hungry for something that doesn't have a name, that you can't find in the store. So you go home and you make it."

The waitress comes over and Waits orders a decaf ("I'll go crazy if I drink the real shit"). The jukebox is playing Creedence Clearwater Revival's Have You Ever Seen The Rain. Conversation turns to Bob Dylan's satellite radio show.

"Have you heard it?" asks Waits, "oh man!" His face lights up. "It's the best. I don't' have that XM radio [he doesn't even use a computer; "I can't turn them on, I'll lose everything"] but my friend taped them for me. And it's almost better than listening to [legendary '60s DJ] Wolfman Jack, just hearing him rattle on about various minutiae and about the world. And the song selection - Sinatra, Johnny Mercer, Judy Garland. We all have an idea that songwriters are purist, that if you like folk music you only listen to folk music, but it's not true. Like for example, Howlin' Wolf loved Jimmie Rodgers and Muddy waters loved Gene Autry, he didn't sit around listening to blues all day. It's like breathing your own oxygen. You've got to find some nutrients somewhere."

He says it's the same for him. He doesn't live his life isolated in a world of Tom Waitsness, but listens to all sorts of stuff, from the astonishing scat/ doo wop stylings of Shooby 'The Human Horn' Taylor to Missy Elliott, while at the same time claiming, "I don't know if I listen to anything that would be really surprising."

As a kid he listened to Jerome Kern and Hoagy Carmichael or Mexican music. "We weren't really allowed to listen to conventional radio. My dad didn't like to listen to anything that wasn't in Spanish, because he taught Spanish. Like he loved Marty Robbins but he went out and got El Paso in the Spanish language, mariachi version of it." When his parents separated, Waits, the strictures on radio gone with his father, listened to the late night broadcasts of Wolfman Jack. "You'd hear Little Willie John and Sister Rosetta Tharpe and it was like entering another world." Going to different worlds is something that stuck with him. For a man with a reputation as a stay-at-home, almost recluse, his songs travel all over, from backwoods America to Berlin.

"I think everybody's looking for something they've never seen before. You work on your songs, but your songs also work on you. So you absorb and you excrete and in some way you retain, and slowly you start to become some place that songs are passing through. I'd like to think that they enjoy blowing through you. There's something electric about you, maybe, some kind of a force left behind by music that passes through you. Like everybody likes to be around someone who does something well and loves doing it, so songs would be no different, right? Like 'Let's blow down there and see that guy'."

Asked whether the first songs Waits ever wrote just blew through him, he squirms. "No, I was.really embarrassed. Early songs are. you're nervous, and you don't really know what to write or how to write about it. I wanted to be original, but nobody creates out of nothing. It's all a question of what you've digested and what's melted in the pot and what refuses to melt and the things you ignore and the things that you celebrate."

At what point did he feel the songs he wrote had become his and not just a collage? "Well once you start, you are forming your own voice as well, which you don't realise. You absorb all these other people that you'd like to be able to sing like but can't. So you just do your own version of them, which sounds a lot like you after a while, and you're stuck with you."

In fact, Waits was well and truly stuck when, aged 30, he met the person who would become his co-writer, saviour and wife, Kathleen Brennan, an Irish-American farm girl from Illinois turned Hollywood script editor. The meeting happened a quarter-century ago, after completing Heartattack and Vine (piano, guitars, strings, no real cohesion, just a sense of Waits poking a hole in the barfly beatnik cocoon) and before Swordfishtrombones (percussion, bagpipes, creepy circus organ, a joyful work of experimental, out-there neo-primitivism), which sums up the Brennan effect.(2)

"You know if a deer gets caught in the garden," says Waits, "they'll throw themselves at the fence until it kills them, because they don't think to turn around and go through the gate. You can try to direct them to the gate but they won't go, they'll keep on that same path. I was a little bit like that, I knew I needed to change but didn't really know how to do it. And then I got married. Nothing that I did in my life prepared me for marriage at all," he laughs. "My wife will attest to that. But I went into it anyway."

What would a fly on the wall see during the co-writing process?

"It would look like two birds in some weird mating ritual probably, kicking up dust, then flying away, coming back. I don't know, once you've had kids everything else is pretty easy collaboration-wise. It's kind of an extension of everything anyway - what you like, what I like, what we like, what I can enlighten you about, what I can hold you down and make you drink."

Asked whether anything makes the songwriting duo come to blows, Waits explains that his wife's big argument with him is that "she doesn't like that I take people's fingers off or give them one leg or make them blind in one eye. She says, 'There's no reason everybody has to missing a finger or having only one good eye. It's just a personality flaw.'"

So he fights for his right to amputatese? "Yes you have to fight. And she fights too. She's a good fighter. She has to be good. She is."

The attraction to the broken, dark and damaged must have come from somewhere. Waits though, has no easy explanation. If pushed he'll say that he was probably more of a Brothers Grimm than a Hans Christian Andersen child, or at least that he "liked to be scared", before adding that all kids do, and that he didn't move on to Poe or look up weird diseases in the library. "No, what I was always looking in the library for was books that had stuff about girls!" After a few moments thought he concludes that what it comes down to is, "Like they say, the way you do anything is the way you do everything. If you have sugar in your coffee there's a parallel in some other part of your life. But I was.I don't know, a pretty normal kid. Although.I thought I was disturbed in a lot of ways, but that was a private feeling about a personal condition. I had things like, when I would rub my hand across a wall, it was much louder than it should have been. And at night before I went to sleep if I moved my hand through the air, it sounded like I was whipping the air with a broom, everything got really intense. It was a form of vertigo and it just came upon me. I didn't tell anybody about it because I thought I'd have to go to the doctors. So I waited for it to pass."

Waits has always said that, as a youngster, his preference for old music over rock, and piano over electric guitar, stemmed from a deep respect for the music his parents liked. Noise-sensitivity also sounds a pretty good reason. "No, I think I trusted a certain amount of my parents' taste about things, and I looked at the songs they liked as curiosities, things that I needed to take apart and see how they were constructed."

So, what's he building in there?

"It's like glueing macaroni to a piece of cardboard and painting it gold, really."

We're sure it's not really like that.

"It's exactly like that."

Where then does the glueing process take place - the garage, a studio, a make-believe world of his own invention?

"You kind of go into the world of a song," says Waits. "They're not necessarily autobiographical, sometimes you inhabit the lives of others. Or it's just a daydream. Songs kind of write themselves sometimes. It's like you're kind of walking out on the diving board and you keep walking until you fall in the water and every line keeps you in the air and if you come up with a bad line you fall into the water. I don't know how it works. If I did I'd probably stop doing it."

The waitress returns with two coffee jugs. Waits leafs through his notebook and pulls out some loose pages of A4 paper containing a hand-written list of curiosities. Like how in the 18th century a popular fashion item was mouse-skin eyebrows stuck on with fish glue. "And it was very interesting that the Theremin(3) was really a failed attempt at a new burglar alarm - that's what the guy who invented it had set out to create. You know when you're on short-wave radio and you get that pyeeew, pyeeew sound between stations? That's the principle of the Theremin: your proximity to the area changes the pitch of the note."

Waits, of course, has had a long fascination with, and collection of, more unusual instruments, his so-called Junkyard Orchestra. It's generally deemed to have been inspired by Harry Partch, the eccentric turn-of-the-20th-century composer and hobo who invented 27 instruments including the chromolodeon (a modified harmonium), monophone (modified viola) and Zymo-Xyl (a xylophone-like contraption made from hubcaps and tuned liquor bottles). Waits had a friend, Francis Thumm(4), "we grew up together", who played chromolodeon in Partch's orchestra when the composer performed at San Diego University. "The only thing about those recordings is they didn't actually capture the resonance of these instruments. They weren't recorded in the right circumstances and it's very difficult - some of these instruments have a very weak signal and if they're not in the right environment it just sounds like you're hitting a table with a knife."

Waits never met Partch but has heard some wonderful stories, and that the person who actually got him started in unusual and ad hoc instruments was "one of your countrymen, Victor Feldman(4). He actually played with The Beatles. A jazz musician, and so knowledgeable." They met in Los Angeles, the city to which both of them had moved, Waits at the turn of the '70s. "And he introduced me to Emil Richards(4), who had such an extensive collection of percussion instruments it just boggled the mind. I was let loose in this huge warehouse of these instruments, to pick whatever I wanted, and I didn't even know what they were: boo-bams and onglongs, things that you could never fathom or understand what they might sound like."

Since he didn't know how he was supposed to play them, he could do what he liked with them. "And that was thrilling to me - to do things to the instruments that perhaps had never been done before, because the hands have so much intelligence, it's important to confuse them now and then, and they'll surprise you and create unfamiliar sounds."

Hence 1983's Swordfishtrombones which, with his wife's encouragement, Waits produced himself. The record company's reaction to the end result was, "Not only will you lose the audience that you have, you won't gain a new one." But as for Waits, "I felt liberated. I had been so frustrated at that point and I felt like I had found my voice - like this is my voice."

As he describes it, his studio approach since that breakthrough album owes a lot to the Surrealists. "I was thinking about when [Antonin] Artaud and all those guys started doing their work, in the photos of them, the table was always full of drinks and somebody was making a weird face and somebody was half-dressed and I like that. What to include and what to exclude wasn't really their job, so I really did like going into a studio and deciding what we're going to hear and what we're not going to hear - because silence is an enormous part of every record, you're always playing it, just like as a painter you're always working with black.

"Some of these songs are like aquariums and you can see things behind other things, everything's moving. You're really trying to capture something that's living. And the songs are living. The trouble with recording, though, is." he scratches his chin and thinks. "I wonder a lot what it was like before recording, because in those days songs were always in flux, being reinterpreted and changed and everyone was a part of it. You heard a song, you learned it, you forgot a verse and you replaced it with a new one, or you changed the details so it fit more in your world locally, or you took some words out because you wanted to sing it to the kids. You were part of the evolution of the song. But now, recording, everything is kind of under glass."

He talks about the Smithsonian Folkways field recordings that the musicologist Alan Lomax made in the 1930s, how he wandered about America with a tape recorder weighing 500lbs, and when he told people he wanted to record them, they'd look at him like he was mad. "It was like someone coming to your house and telling you 'I want to take all your pictures that your kids did on the refrigerator and put them in a book.all those rocks in your driveway, I want to make rings out of them.' What are you talking about! The beauty of it was that the recordings were made completely unselfconsciously, so there was a real sweetness to it because they were singing into a device that they'd never seen before and, unlike a band who know who their audience is, they didn't know who they were singing to.

"I've read reports that some, when they listened back, would want to do another take and he would say, 'No, it's good when the dog barked and your wife knocked over the glass, it's real that way.' And for me it's like early Bob Dylan bootlegs, where there was such dramatic fidelity changes from cut to cut on the record, all from different sources. I think that's why I like these old field recordings, because there's other things going on in the room when the recording was made and they were captured, life was captured, and it was very primitive. And the songs and the people and all of that became one thing for me."

Does he already know when he goes into the studio that one song might require a bassoon and banjo or another a calliope? "I think sometimes if a song is very well-constructed it doesn't need a lot of gewgaws, it doesn't need a lot of jewellery, and sometimes what you're adding to the song is a hairnet and a wristwatch and yellow socks. Some songs are created under very difficult circumstances and sung in luxury, and others you'll write in luxury and perform them under very difficult circumstances. You never know."

Waits is on his third cup of decaf. We're talking about cover versions of his songs - a varied bunch, from The Ramones (I Don't Wanna Grow Up) to The Eagles (Ol''55), Bob Seger (Blind Love) to Bette Midler (Rainbow Sleeves)(5). In the past Waits has been less than complimentary about people tackling his material - protecting, perhaps, the Tom Waits magic/ myth by keeping them the way he wrote them. It seems linked to the passion with which he's fought to keep his songs - or even soundalikes (his most recent victory against the Opel car company)(6) - out of commercials.

"There is a certain question of, well, this is my property, not your property," he says. "Like, You can't hunt on my property. But beyond that, it's more that songs have great value to me, they have meaning, and if you pervert the meaning - which is what it really is, what you're saying is 'While you're enjoying this song, and all your rich, warm, delicate, tender memories of what that song means to you, I want you to be thinking about toilet paper and buying it'.Bob Dylan did underwear, I have to say that baffles me. He was probably just trying to dispel every myth you have about him, to take your perception of him and crack it open. But a lot of people take the view of "Hey, it's just a piece of commerce anyway, a song, so I might as well just sell it to as many different people in as many different ways as I can."

A bit like having a daughter and then sending her out to work the streets? "Yeah, there's a lot of money in that, honey."

When other artists covered his songs he admits he never used to like them. "But I came around to thinking that it's a good thing," he says. "They're saying that there's something in there that's beyond its own personal revelation to you, something that is somewhat universal, the truths or the feelings are broad enough that they can be incorporated into somebody's else's experience, and that's good. You're always anxious to hear your songs done by someone you admire or respect, because that's what it's all about. Johnny Cash did my song [Down There By The Train] and I was, OK, that's it, I'll be leaving. I was already thoroughly satisfied."

As to how other artists might feel about him covering their songs - again a pretty varied bunch, from The Ramones to Red Sovine, Leonard Bernstein to Daniel Johnston - he says, "I guess I was hoping that if Daniel Johnston heard [Waits' cover of King Kong], he would like it." Waits appeared on the Daniel Johnston tribute The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered (2004) curated by Mark Linkous of Sparklehorse. Waits tells an animated story of how that project came about, how Linkous's mum was having her hair done at the same salon as Daniel Johnston's mum had hers done, and they started chatting under the hairdryer about their children: "Oh, my son's in music as well."

Waits laughs, "Oh man. My mom does that all the time. She'll just blurt it out: 'My son's in music.' She'll say it in line at movies, turn to total strangers, 'My son here is in music.' We're in a record store, she'll yell out, 'This is my son, he's here to buy some music, and he makes music, in fact he has his own bin here!' Jesus mum! Stop it."

As for movies, there's not much going on, although he wrote some music for director friend Roberto Benigni's The Tiger And The Snow and played a trailer park operator in Wristcutters, a low-budget road movie by Croatian director Goran Dukic in which the protagonists are the spirits of suicides. Waits doesn't hold out much hope of it coming out, other than maybe in Croatia, and doesn't seem too bothered.

"I'm not an actor. I just do a little acting, like I do a little instrumental repair." Has his film work affected his songwriting? "Only in that when I'm making songs I'm the actor in the songs. Like, what's the voice for this song? What should this guy be wearing in this picture? You do that all the time when you're making songs, because you want it to be everything it can be."

What in his opinion are his overlooked or forgotten songs? "I don't know. It's not like I've got these huge big hits and then I've got these little guys who've never had a shot. They're all kind of fledglings, so I don't think of them as ones that made it all the way to Florence and the guys that stayed in town. I more look at them for the seeds of my breakthroughs so I can see, Oh there's a little thing I was trying to do, or, there's an unusual sentence there, and the next one you expand on that. They're all good for something."

The bar's empty now, it's that twilight hour between day and night. The waitress brings the bill. MOJO asks, as we get ready to leave, if Waits, a gerontophile since childhood, feels that now that he's older he's grown into the self he always wanted to be.

"Somewhat," he says. "But I don't know what it is, you want to show your kids that you are still young and vital and you can jump off the roof with them with a towel for a cape and do a back flip on the trampoline and shoot hoops until it's dark. Because they want to know: Can they push you over? Can they break your neck? What are you made of? Does your dad push back?"

Waits pulls a banknote out of his wallet and pays the waitress. "I used to want to be an old man when I was a kid," he says. "Now I'm an old man and my kids are growing, I think I want to be a kid."

Postscript: The Heirloom tomatoes were delicious.

"Wool of Bat and tongue of dog"

The strange and varied ingredients that helped to make Tom Waits

By Clive Prior

ALAN LOMAX

Born in Austin Texas in 1915, the son of musicologist John Lomax, Alan spent his life chronicling folk music from the world, recording Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Muddy Waters and Jelly Roll Morton as well as gospel church services, the songs of prisoners and farm workers, and the folk songs of Scotland, Ireland and Italy. He died in 2002. More info: alan-lomax.com

KATHLEEN BRENNAN

Waits' wife, collaborator and inspiration, Brennan was born in Johnsburg, Illinois, as noted in Waits' song of the same name. They initially met on the set of Sylvester Stallone's 1978 film Paradise Alley - he had a bit part as a piano player and she was story analyst. They hooked up again on Coppola's One From The Heart in 1980 and married in LA at the Always & Forever wedding chapel. "I was such a one-man show, very stuck in my ways," says Waits. "She helped me rethink myself." More info: tomwaits.com

WOLFMAN JACK

With the on-air cool of Alan Freed and the smokestack growl of Howlin' Wolf, Robert Weston Smith - a young white man from Brooklyn - remade himself as DJ legend Wolfman Jack. Broadcasting from super-power Mexican transmitters from 1958 to 1966, Jack covered the US with his lawless mix of blues, rock'n'roll, R & B and jazz punctuated by hip growls'n'howls. He died in 1995 aged 57. More info: Wolfmanjack.org

VICTOR FELDMAN

A child prodigy on the drums who sat in with Glenn Miller's Army Air Force Band, aged seven, London-born Feldman led his first band in 1948 aged 14. Touring as vibist with Woody Herman, he then moved to the US to play with Cannonball Adderley and Miles Davis, later hooking up with The Beatles, Frank Zappa, Steely Dan and Waits, playing conga, marimba, boo bams and possibly onglongs on Swordfishtrombones. More info: Jazzprofessional.com

ANTONIN ARTAUD

Drug-addicted poet/actor in early 20th century Paris who crafted confused primal theatre project The Theatre of Cruelty. Travelled to Ireland to return a walking he believed belonged to St. Patrick, Lucifer and Christ. Was attacked, deported and put in a straitjacket. After the war composed a scatological anti-religious percussive play for French radio, deemed unfit for broadcast. He died on March 4 1948. More info: antoninartaud.org

SHOOBY 'THE HUMAN HORN' TAYLOR

Born in Pennsylvania in 1932, Taylor grew up in Harlem with dashed dreams of playing jazz sax. Realising 'I am the horn!', he crafted an absurdist vocal bebop sound. An early '80s session made its way to Jersey City radio station WFMU and he earned cult status. Tracked down by Elektra's Rick Goetz and WFMU's Irwin Chusid in 1995, Taylor was invited onto The David Letterman Show, but was too ill to perform. He died in 2003. "Wool of Bat and tongue of dog"

EMIL RICHARDS

A child prodigy on xylophone, Richards was playing with Charles Mingus, Ray Charles and George Shearing before he was 21. In 1962 , on a world tour with Frank Sinatra, he became interested in ethnic percussion and began working with Harry Partch, and has since built up an array of ethnic percussive instruments. More info:emilrichards.com

HARRY PARTCH

The California-born son of Presbyterian ministers who'd fled the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1901, Partch learned to play clarinet, harmonium and guitar as a child and began composing to his own 43 tone scale to accommodate the contours of human speech, constructing a monophone or adapted viola to help with his task. After living as a hobo in'30s America, he received a grant in 1943 and expanded his instrument repertoire to include such wonders as the Diamond Marimba, the Boo and the Quadrangulis Reversum. He died in 1974. More info: harrypartch.com

"Clang Boom Steam"

The strangest engines in Tom Waits' workshop by Andrew Male and James McNair

PASTIES AND A G-STRING

Scatted, Beat-style poetry and veteran jazzer Shelly Manne's tight-but-loose drums were all Waits needed to sketch a sleazy, ultra-vivid night out in the environs of Hollywood's Tropicana Hotel, home for Tom when he penned this. No 'proper' instruments at all on the recording - just proof that rhythm is a (burlesque) dancer. Available on: Small Change

UNDERGROUND

The previous studio cut from Waits had been the maudlin music-box coda on the 1982 soundtrack to One From The Heart. And now this? Fired by the arrival of Kathleen Brennan in his life, Waits is reborn as a bellowing carny barker alerting the world to an alternative subterranean metropolis against mallet acoustics and Carl - Stalling cartoon nightmare guitar. Available on: Swordfishtrombones

TOWN WITH NO CHEER

A bagpipes and harmonium bolstered ballad about a parched Aussie ghost town on an album influenced by Kurt Weill and left field composer Harry Partch? Could work. All together now: "There's a hummingbird trapped in a closed-down shoe store." Available on: Swordfishtrombones

MIDTOWN

A real screeching Winsor McCay '40s nightmare in which Waits summons up Stan Kenton's big band demons to score some Benzedrine-bent sax-squealing belt into a dive-bar jazz subterranean. The soundtrack playing in the head of whoever killed The Black Dahlia. Available on: Rain Dogs

IN THE COLOSSEUM

You thought it the preserve of TV quiz shown Countdown, but The Conundrum is also a crude , rack-mounted percussive instrument of Waits' own invention, deployed to pummelling , near relentless effect here. Amid the tumult, Larry Taylor's upright bass gets fed to the lions - but in a good way you understand. Available on: Bone Machine

WHAT'S HE BUILDING?

From out of broken radio buzz, and blacksmith hammering, Waits stares into his neighbours frontyard junk asks "What the hell is he building in there?" as sounds bleed upwards from the pipes: gongs, groans, glissandos and splintered wood. "I'll tell you one thing, he's not building a playhouse for the children." Available on: Mule Variations.

CALLIOPE

Decidedly noir dissonance warily parped on trumpet and wheezed through the shot-sounding lungs of the titular steam organ.Though Knife Chase, another instrumental from the same album, gives Calliope a run for its money scariness wise, this track's deranged-sounding toy piano and unnerving closing cackle make it the one to spook your kids with. Available on: Blood Money

KOMMIENEZUSPADT

Oh Lord! As some kind of rusting clockwork mechanism tightens round a captive klezmer band, Waits spits out demonic German incantations summoning up a Weimar jazz march of bellows, roadside drills and blood-flecked laughter. Wasn't this meant to be his romantic album? Available on: Alice

TOP OF THE HILL

In which Tom's Clang-Boom-Steam sound gets stoked by son Casey's scratching turntables, then hauled back across the engine-room floor by Marc Ribot's taut, garrotting guitar. Another envelope pushed and more daytime radio pluggers confounded,one suspects , our stubborn old buzzard continuing to do it his way. Available on: Real Gone

HEIGH HO

Employing the rusting doors of hell for percussion and what sounds like a lung-busting accordion for the melody, a sepulchral Waits howls in tongues from some unholy toiling railway hell. What is he singing? Hang on, it's the reworked lyrics from Snow White and The Seven Dwarves! Now I am scared. Available on: Orphans

Notes:

(1) To meet in a roadhouse: Dutch version of this interview previously published in Revolver magazine: "Tom Waits: Vader Duwt Terug", Revolver magazine #7 (The Netherlands). January/ February 2007

(2) The Brennan effect: Further reading: Quotes on Kathleen.

(3) The Theremin: Further reading: Instruments.

(4) Francis Thumm/ Victor Feldman/ Emil Richards: Further reading: Who's Who?

(5) Rainbow Sleeves: read lyrics: Rainbow Sleeves

(6) Victory against the Opel car company: Further reading: Waits v. Opel.