|

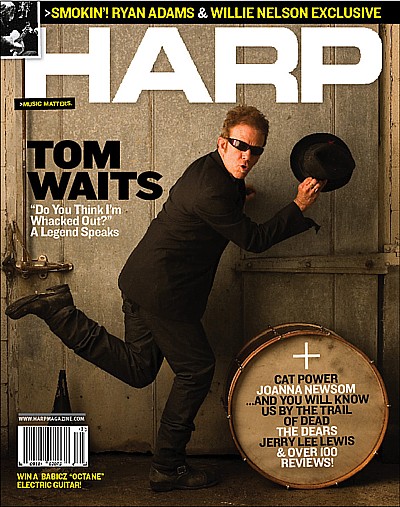

Title: Tom Waits: Weird Science Source: Harp magazine (USA), December 2006. Telephone interview by Mark Kemp. Copyright 2002-2006 Guthrie, Inc. Photography by Michael O'Brien Date: Published December 1, 2006 Key words: Orphans, Heritage, early years, pop music, changing labels, Frank's Wild Years Magazine front cover: Harp magazine (USA), December 2006. Published: December 1, 2006. Photography by Michael O'Brien |

Tom Waits: Weird Science

By Mark Kemp

Whack

v.tr.

1. To strike (someone or something) with a sharp blow; slap.

2. Slang: To kill deliberately; murder.

n.

1. A sharp, swift blow.

2. The sound made by a sharp, swift blow.

Whacked-out (slang)

1. Exhausted.

2. Crazy.

3. Under the influence of a mind-altering drug.

"Do you think I'm whacked-out, Mark?"

Tom Waits asks the question in the same rasp he uses in his early, jazz-based Beat-poet work, not the croak and wheeze he's developed since he started banging on pots and pans and delivering lines like "Bring me some water, put it in this skull."(1)

I hadn't exactly called him whacked-out. My initial line of questioning involved a characterization of the range of music on his new three-disc collection, Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers & Bastards (Anti). Its 54 songs run the gamut from ancient-sounding ballads (the gorgeous, pedal-steel-fueled "Tell It to Me") and rockabilly barnburners ("Lie to Me") to the spitting, sputtering "Spidey's Wild Ride"- the kind of song I had described to him as his more "whacked-out avant-garde stuff."

I figured it was a safe enough depiction. After all, Waits' music jibes with many of the whacked-out definitions: It strikes with a sharp blow; it slaps; it sometimes deliberately kills. It's a little crazy, and some of it may even be under the influence of mind-altering drugs. But words like whacked-out, weird and strange don't mean much to Tom Waits.

"What's strange? What's weird? That's very personal," says Waits, speaking by phone from his home "in the middle of nowhere," somewhere among the wineries and marijuana farms of northern California. Waits himself doesn't even drink anymore, much less smoke dope. He's been sober for more than a decade and living a rural existence with his family ever since he returned to the West Coast from New York City in the late '80s. He'd met his wife and longtime musical collaborator Kathleen Brennan, in 1980, during the filming of Francis Ford Coppola's One From the Heart. Waits had written the soundtrack and performed it along with country singer Crystal Gayle; Brennan was the script analyst. It was love at first sight. The couple have since produced three children together-Kellesimone (born in 1983), Casey Xavier (1985) and Sullivan (1993)-and a handful of bona-fide experimental classics including his '80s Frank trilogy (Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs and Frank's Wild Years), 1992's Bone Machine and 2004's Real Gone.

Orphans is a hodgepodge of 24 "lost" songs and 30 new ones, and includes unlikely covers ranging from a croaking, accordion- and piano-fueled barroom sing-along of Leadbelly's "Goodnight Irene," to a terrifying take on troubled indie poet Daniel Johnston's aching "King Kong." Waits' son Casey sits in on drums for one of the new tunes, a lo-fi, Stones-like rocker called "Low Down." To be sure, Orphans offers up plenty of Waits' surreal lyrics and bizarre Beefheart-like narratives. In "Army Ants," he reels off vivid descriptions of disgusting insect behavior. It's all allegorical, of course- Waits is making a statement on humanity. Or maybe he's just trying to find the right words for the right sounds.

"You know, you can't see music, so sometimes talking about it is difficult. So you use metaphor," he says. "When you're speaking to musicians, you use images. You say something like, 'Hey Joe, make it like the hair in the gate-a little more like the hair in the gate.'"

The hair in the gate?

"It's that big ball of hair that somehow got attached to the celluloid [in a movie theater], so for a minute you're watching this big piece of hair trembling and vibrating on the screen and then suddenly it flies off," Waits explains. "So that's the kind of thing you use as an image of what you want something to sound like." He hacks out a laugh. "Or I might say, 'Hey Marc, play like your hair's on fire.'"

This, by the way, is something he once said to guitarist Marc Ribot, not yours truly. But a conversation with Tom Waits can be a little like running in circles with your hair on fire. He hates direct questions. When he doesn't want to talk about a certain topic, he'll veer into a protracted discourse on albino moles, artistic horses or ceramic plates.

"Did ya know you can play a ceramic plate backwards and hear the voices of the people who made it? You didn't know that, did ya?"

Way Down in the Hole

Tom Waits was born in the Los Angeles suburb of Whittier in 1949, and raised in a home where his father, a high-school Spanish teacher, listened to mariachi music and records by Harry Belafonte, Bing Crosby and Marty Robbins. Waits was about 10 when his dad left the family; Tom and his mother relocated to San Diego, where he would attend Hilltop High School in nearby Chula Vista. After holding several jobs in the area, including a stint at a pizza parlor where he'd punch in Patsy Cline and Ray Charles songs on the jukebox, Waits became the doorman at a popular Mission Beach folk club called the Heritage(2). It was only a few short steps to the stage, and Waits eventually got the chance to perform his own versions of songs by Bob Dylan, Mississippi John Hurt and the Rev. Gary Davis.

"I was just waiting for my balls to drop, like everybody else," he remembers. "Most people just do very bad impersonations of their favorite singers, so you know, that's what I was doing. It was a failed attempt at an impersonation of Ray Charles or Bob Dylan. I hadn't really found my voice yet; I didn't really have a voice yet. I just had this.I don't know what it was, but it certainly wasn't my voice."

Even then, his madcap eclecticism revealed itself. Dave Robinson, a performer at the Heritage, told Waits expert Pieter Hartmans, "I remember once coming into the club early to set up for the night's performance. Tom was sitting at the Heritage's ancient piano reading from a sheet of music, some Tin Pan Alley song from the '30s or '40s. It could have been Gershwin or Cole Porter, but to me, back then, it just seemed kind of funny that a guy in a folk club would be interested in anything so far outside of the usual folk category."

By the early '70s, Waits had landed gigs at the famed Troubadour in Los Angeles(3). That's where Herb Cohen, manager of Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart, first heard Waits and offered to manage him. In 1971, David Geffen signed the young singer/songwriter to his new Asylum Records label, home of Jackson Browne, the Eagles, Joni Mitchell and even, very briefly, Dylan.

"I started recording when I was pretty young and pretty naive," Waits remembers. "And you know, I wasn't really in the world yet. I mean, the way you do anything is usually the way you do everything, so I was fairly naive about the whole music business and all that, and very naive as a composer."(4)

He says listening to his earliest recordings of songs like "Ol' 55"-later covered by the Eagles on their On the Border album-is akin to "looking at baby pictures. Like jeez, where'd he get those pants and that haircut? Hopefully you wind up morphing into something that's more like you."

Within three years, Waits had morphed into something that looked, well, a little like the Dean Moriarty character in Jack Kerouac's On the Road. The singer lived in Hollywood's seedy Tropicana motel, sported a goatee and wore old tweed caps, rumpled skinny ties and wrinkled baggy clothes. His voice had become a cigarette-wrecked growl, and his jazz-backed narratives were peopled with hookers, grifters, barflies, snake-oil salesmen, characters with names like Bubba and Big Joe, and his real-life musician friend Chuck E. Weiss (the one in love in with Waits' one-time girlfriend Rickie Lee Jones).

"I'd read Kerouac when I was a teenager. That was profound," Waits says. "And you know, I immediately wanted to get on the road and start hitchhiking. And I did. I went all over-I went to Arizona, Oklahoma, Texas-just to get out there and see what it feels like. Everybody wants to try and jump off something that's higher than he can handle, just to see if he'll float quietly to the ground or break up on the rocks. Everybody wants to see what the world's made of and wants to see what they're made of. I think that was the best time to hitchhike. Back then you didn't worry so much that the next driver would have a cigarette lighter or a chainsaw going [makes the sound of a chainsaw cutting through flesh] REHHHHH."

In a musical era overpopulated with coke fiends and jaded hippies, Waits was the personification of a new kind of vintage cool-a technologically advanced hipster. Raymond Chandler for the counterculture. Hoagy Carmichael for folkies. Lord Buckley for the Cheech and Chong generation. But by the late '70s, Waits had veered dangerously close to self-parody.

"You know, in my early days, I was just studying the whole thing, trying to find out what I could bring to it that hadn't been brought to it before," he says. "Which is really hard to do. Most American culture-we just bury things so we can dig them up again. There's nothing new under the sun, certainly not in popular music. By its very nature, popular music is repetitive and it's constantly masquerading and then exposing itself again. If you just keep stirring it, different things come to the surface. So it's sort of interesting to watch what's bubbling up. What you recognized from before that you thought had gotten hidden at the bottom is now up at the top again."

Down, Down, Down

The mellow Californian sound had given way to punk rock and hip-hop by the time Waits decided in the early '80s that he wanted to produce his own album-something that would sound completely different. He'd been inspired by his new wife, Kathleen, who encouraged him to continue digging to his creative core. The couple had an idea for a story revolving around a guy named Frank. Waits would bring in new instruments and experiment with old melodies in new ways. So he and Kathleen walked into the office of Asylum Records president Joe Smith one day with a proposal.

"In those days, people didn't give money to an artist and say go produce your own record," he says. "They gave it to a producer. If they gave it to an artist, it'd be like throwing the money away. They thought you'd spend it all on drugs or women, or you'd go to Mexico or who knows what. So they wanted you to get in there with a guy with a better haircut. Not necessarily better ideas, but a better haircut and cleaner clothes."

Waits and Kathleen-along with a new crew of musicians-produced four or five tracks and brought them back to Smith.

"He hated it," Waits remembers. "I mean, this is a guy who looked like a sports announcer, so I didn't really have much of a rapport with him. I felt like I was talking to an insurance agent. So he says to me, 'You're going to lose all of your old fans and you won't get any new ones.' I think he even called me 'kid.' He fancied himself as something of a mob boss but he also had a little bit of a fraternity feel to him. It was discouraging, but we were able to get off the label on a loophole."

Shortly thereafter, Waits ran into Chris Blackwell, owner of Island Records, whose biggest act had been Bob Marley and the Wailers. In 1980, Blackwell signed a little Irish alternative rock band called U2 and was ready to experiment with other adventurous artists.

"He loved the record," Waits remembers of his meeting with Blackwell about the album that would become the brilliant Swordfishtrombones.

"He came out to L.A., we had coffee and he said, 'Yeah, I'll put it out.' And that was it. So we moved to New York and were there for three or four years."

It was Tom and Kathleen's wild years. By 1987, Swordfishtrombones had spawned Rain Dogs and Frank's Wild Years, a trilogy from the couple's most fertile period. Waits was dazzlingly creative, digging, digging, digging.

"I was a mole," he says, "a mole in a hole, tunneling beneath the great river. You know, one false move and the water fills your tunnel and you wipe out hundreds of mole communities." He pauses for dramatic punctuation: "You must be very careful."

But just who was that Frank character? Was he named after Zappa? After all, the short narrative "Frank's Wild Years," from Swordfishtrombones, had been dedicated to Frankie Z.

"Gee, I don't know," Waits says. "My dad's name is Jesse Frank. It's just a name. It's just a guy I half made up. My dad left the family when I was young, so you know, that's pretty eventful. I may have been telling some of that story-'He got on the Hollywood Freeway and headed north/Never could stand that dog'-it was probably a reaction to that. I was rewriting the story and putting it in my own language."

It was a hell of a language, one that initially characterized Frank as a husband who snaps and sets his house on fire. By the time of '85's Rain Dogs, Frank had become a man who'd "seen it all through the yellow windows of the evening train." He was a drinker, a traveler, a madman, and Waits told the story of Frank cinematically, in a voice that recalled bluesman Howlin' Wolf and with melodies straight from the Kurt Weill songbook.

"I'd had somebody come up to me earlier and tell me to check out Kurt Weill- said, 'Hey, you kind of sound like him.' It was just kind of happenstance."

Critics raved over the Frank trilogy. It was Waits' first reinvention of himself as an artist. It wouldn't be his last.

All Stripped Down

Kurt Cobain's band Nirvana, by way of his heroes Sonic Youth, had help introduce the mainstream rock world to dissonance by the time Waits and Brennan surfaced with Bone Machine in 1992. It was another reinvention, one that discarded the marimbas, accordions, pump organs and surreal carnival songs of the Frank years in favor of a raw, primitive, lo-fi, blues-based sound. Bone Machine was terrifying, an apocalyptic nightmare of clattering junkyard decay that didn't let up for 14 of its 16 tracks. The album-along with The Black Rider, Waits' operatic collaboration with William S. Burroughs and Robert Wilson-was a fitting finale to Waits' Island years. He was so far down in the hole now, stripped of anything resembling mainstream popular music, that a small independent label, Anti, would be the only logical next turn for him.

Waits' subsequent releases for Anti-1999's Mule Variations and 2004's Real Gone, in particular-built on the stripped-down apocalyptic blues of Bone Machine. His ugly croak turned out to be a beautiful instrument, and Real Gone, his grittiest album to date, miraculously became Waits' highest charting release, peaking at number 28 on the Billboard 200. Even the superficial Entertainment Weekly weighed in with a goofy review that included the mystifying praise, "Often riveting-and even a little gangsta." Between Mule Variations and Real Gone, Waits and Brennan also released the melodic and tender Alice and Blood Money.

"I think the key to staying around is diversification," Waits says. "You have to be able to speak several languages, or at least that's the way I've always seen it."

He goes off on one of his tangents. At first, it doesn't seem relevant, but by the time he gets to the end of the story, I begin to understand the hodgepodge that constitutes Waits' new collection of Orphans.

"You know, they found a set list inside of a guitar that had belonged to Memphis Minnie, and the first song on the list was the Woody Woodpecker theme song," he says. "That's because she played places where there were kids, and you gotta have something for the kids. Then later, when the kids were asleep, that's when she could do stuff like 'Don't You Ever Wash That Thing?' or whatever you call it."

Never mind that Waits has just referenced a Frank Zappa song rather than a Memphis Minnie song-his point remains: A real artist juxtaposes innocence with sleaze, beauty with repulsiveness. A real artist doesn't stick around the same watering hole for too long.

Sweeping all the disparate, wayward songs together for Orphans was a feat Waits wasn't exactly prepared for.

"I don't keep good records," he says. "I don't have a vault where everything's organized, so sometimes I lose stuff. If I'm not careful, the stuff that never had a home winds up in a drawer in a pizza box with hair oil and playing cards. Then I find it again and I feel like I'm seeing it for the first time."

Some of the songs-he can't remember exactly which ones-came from a fan in Russia.

"I paid the guy some money and he sent me a bunch of tapes," Waits says. "I don't know how people get a hold of this stuff. You have an engineer who was there when you recorded this and that, and he makes a copy and sends it to a taxidermist, and then he sends it to his brother who's a motorcycle repair guy, and then.I dunno, before long your stuff is all over the place."

Waits is bored with my direct questions about the songs and abruptly changes the subject once more.

"You know, I have a friend who teaches guitar at San Quentin, and he said the second day of his classes everybody needed new guitar strings. Y'know why? Turns out they were tearing out the E strings and using them as needles to do tattoos."

First printed in December 2006

Notes:

(1) Bring me some water, put it in this skull: quoting from Earth Died Screaming of Bone Machine

(2) A popular Mission Beach folk club called the Heritage: Further reading: The Heritage

(3) The famed Troubadour in Los Angeles: Further reading: The Troubadour

(4) And very naive as a composer: Further reading: Copyright