|

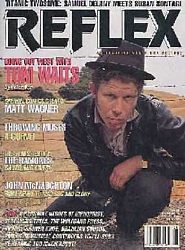

Title: Tom Waits At Work In The Fields Of Song Source: Reflex magazine, #28 (USA), by Peter Orr. Transcription by Larry DaSilveira as sent to Raindogs Listserv Discussionlist, September 1, 1999 Date: Rinehart's/ Petaluma. October 6, 1992 Key words: Bone Machine, Photo sessions, Interviews, Percussion, Studio recording, Composing, Kathleen, Medicine, Larry Taylor Magazine front cover: Photography unknown |

Tom Waits At Work In The Fields Of Song

Rinehart's Truck stop Cafe lies right off the Petaluma exit on the Pacific Coast Highway. To either side loom lush hills prowled by cows. Walk across Rinehart's parking lot and your shoes get caked in wheat-colored powder. When Tom Waits' 1965 Coup de Ville pulls in, I notice that his car's finish matches the dust. This could be coincidence or camouflage.

First things first: photo session. "I hate having my picture taken," he grumbles. "I liked it when I was, like, twenty-five. Long time ago." Strangely, the presence that turns up in the photographs barely resembles the guy. Same hat, same frayed leather jacket, same features, different person. Harsh, shadowy creases appear when the shutter clicks, lending Waits' face an unsettling grimness. In person, he passes barely noticed among the crowd of truckers and Harley enthusiasts. At least one waitress knows him by name, and they leave us alone at our table in the corner. "I can't stand when they buzz around you, asking if everything's okay," he says. "I hate that shit."

You can tell. While's he's not what you'd call shy, Waits has long grown weary of dragging around his reputation as a booze-addled, nocturnal hipster, and thus watches what he says. Too many people have asked too often about his personal life. It's a wonder he never punches interviewers. "I do, now," he corrects me, deadpan. "When people ask you certain questions for the first time, you say a lot of ridiculous things because you can't believe this could show up in print. And then there are performers who use the press for some sort of confession. That doesn't help me." The way to make him relax is to talk about music.

At least twice during his 20-year career, Tom Waits has managed to forge a fresh genre without becoming mired in it. His classic '70s albums for Elektra/Asylum - particularly the heartrending "Small Change" ('76) and "Foreign Affairs" ('77) - established his role as Beat storyteller par excellence, which only made the visionary "Swordfishtrombones" that much more jarring when it surfaced in 1983 on his new label, Island.

Where the key signatures of his Elektra/Asylum work were jazz chops and stunning lyrical detail, "Swordfishtrombones" fueled itself on pure instinct. To be sure, the early LPs were never all kisses and Kerouac; Waits had broken ground with violent urban narratives like "Small Change (Got Rained on with His Own .38)" and "$29.00 and an Alligator Purse." But nothing in his canon hinted at the madness on his Island debut. Linked by the menacingly half-told saga of accordion-playing murderer Frank O'Brien(1), these songs brimmed with a patently American evil. Weird combinations of instruments (including brake drums, chairs, and the glass harmonica) alternately barked and crooned. The piano wasn't just drinking, it was on a rampage.

In interviews, Waits confided that Frank had come to him in a dream, leading many to deduce that the record's nightmarish soundscape merely replicated the artist's dreamworld. This explanation has proven too simple in light of subsequent releases "Rain Dogs" ('85), "Frank's Wild Years" ('87), and "Big Time" ('88), all of which bore, to one degree or another, the mark of Frank. Waits' newest offering, "Bone Machine", affords us a clearer overview of exactly what he has departed from during the past decade: Essentially, Waits now extends his creative process into the very mechanics of recording. No longer are his songs complete entities before the sessions begin. His new work still sounds apiece with any of his Island albums, yet infused with a wicked vibrancy.

The words hark back to the Elektra/Asylum efforts by invoking genuine tragedy. Waits' subject matter once again bounds from road trips to farm philosophy to obituaries; almost all the songs completed by presstime refer to both the Bible and murder. Providing most of the percussion himself (in addition to his usual instrumental duties) enabled him to capture precisely the rough textures that bring these pieces to life. This is an album with all its edges not only exposed, but proudly displayed. It will also further widen his audience to include more alternative listeners--people to whom a new Tom Waits record is "just one among millions of musical sperm trying to break the egg of commerce," as the singer puts it. The deluded, gleeful punch of "Goin' Out West" should do the trick.

The other field in which Waits garners much attention these days is film, as both actor and composer. His 1982 soundtrack for Francis Coppola's "One from the Heart(2)" received an Oscar nomination, and this year his music for friend Jim Jarmusch's "Night on Earth" went over than the flick itself. Aside from the actual songs (co written, like most of the new album, with wife Kathleen Brennan, who wants you to try the pelemeny if you ever make it to Rinehart's), the smoky Jarmusch score came into being as a replacement when another composer's already-recorded work didn't gel with the director's ideas.

"John Lurie is the master of film music," Waits says. "He did Jim's last two pictures, but he was busy. Sometimes it's good to work with limitations; you make something from what you have. Sometimes you need the drama of having to create this thing in an hour. It's not something I have at beck and call. I have a special rapport with Jim."

One longstanding Waits hallmark has been the intensely personal nature of his work. "It's like looking at baby pictures," he shrugs when asked about his early records. To him, the incomparable "Nighthawks at the Diner" ('75--if you've never heard it, no shit, it gets my vote for best live LP of all time) is like that yearbook photo of you pouring beer over your head, the one your parents are so proud of. Which is why Waits doesn't warm to comments like, "You don't look as though you sleep on the sidewalk." Which is why he doesn't do too many interviews.

R: These new songs are quite scary. Is that deliberate?

TW: I'm not sure. I like to be frightening sometimes. I don't think the record's as scary as I would like it to be. Some people do it with volume. I've heard live bands that were very simple but very loud. It's scary to hear music that loud sometimes. That makes you feel like you're sitting in a pit, or what it feels like to be an insect. I love that. This is something that never had a place in a show of my own, but I'm fascinated by that. I love it. It's great when the music can move you like that. But this, I don't know--scary suits it sometimes, I've said so myself. I have a lot of violent impulses. It gets channeled into music. I like to play drums when I'm angry. At home I have a metal instrument called a conundrum(3) with a lot of things hanging off it that I've found--metal objects--and I like playing it with a hammer. I love it. Drumming is therapeutic. I wish I'd found it when I was younger.

R: The bizarre percussion was one of the first differences people noticed about your Island records.

TW: I was very angry when I was making "Swordfishtrombones." I have impulses that I possibly sublimated for a long time. Now I've got drums at home. I just go out in the garage and beat 'em hard. I'd encourage everybody to try that when you're mad. Or anytime, but especially when you're mad.

R: "A Little Rain" is so mournful. It seems like it's about a teenaged runaway turning up dead.

TW: Around here, these small-town newspapers, they cover a lot of murders and a lot of car accidents. I don't know if there are more car accidents and more murders, or if they just get more upset over them. There's something in the way they write about them...it's like a warning. For some, you know, murder is the only door through which to enter life. That's a rough one to think about. Maybe in the cities it seems more commonplace because it's against a backdrop that is also violent. Here, where you see the golden fields or whatever, it's in greater relief. Stark contrast. [Indicates tape recorder] Is this what we're talking into? How are you going to hear what we're saying with all this noise in here?

R: Oh, this thing's amazing. You ever play with a voice-operate mike? I know you like weird tape recorders.

TW: Yeah, I do have a fondness for pawnshop tape recorders--you know, equipment you might find at a swap meet. I've always liked that. You can make a record anywhere with DAT now. You can make a record literally in your bathroom, and go right to 24-track with it. It's changing everything. My theory is that music doesn't like to be recorded, so the more you can do to go out in the field and find it where it is, or take it to a place where it's more comfortable than in a studio, the music is more prone to actually staying on the tape. While you're recording it, you're dealing with a living thing. You're making it, you're changing it--you might be tearing its wings off, you don't know, because you're working with something you can't see. So a lot of times you can be very irresponsible in a studio. That's why the best people to record you sometimes can be very naive about it, and it comes out great, instead of having some guy say, "Oh, we'll do this to it, we'll do that, we'll bring it over here and nail it to this piece of wood." A lot of times what you end up doing is catching the clothes that music was last wearing. The music is slippery. Like in the cartoons when you grab for a character and you get his underwear. A lot of what you're hearing on record is music's underwear, not the music.

R: Is this why you've said you dislike certain earlier recordings?

TW: The trouble is, as soon as you've done something, how you feel about it is changing. And the music's changing, too, because the world it lives in is changing around it. Some of 'em are just good memories. You look at it and say, "Oh, yeah, I remember that." But once you finish something, you literally release it. You've had it for a long time. Only you had it, no one else. And then suddenly, it's like a captured animal or something. You do all you can for the music, and then you release it, you let it go. It comes back. Sometimes it brings you back money.

R: Sometimes you find Bruce Springsteen singing to your girl(4).

TW: All kinds of things can happen. You know, people write and say, "This song you wrote helped me through some hard times," or "Your song always reminds me of Jimmy, and Jimmy died--I think of him every time I hear it." Whatever it is. People make those connections. I do the same thing. I have very visceral attachments to music that fix the music and fix the time that I was in with the music and wed them together. I can't change that.

R: You write songs much quicker than you used to.

TW: Yeah. Some things are best written fast. And you can still spend a lot of time developing it. Recording is not as simple for me as it once was. I used to go in and sit at the piano and sing the songs and leave. I was afraid to do anything else.

R: Is that why "Small Change" was done live on a two-track?

TW: Actually, that live two-track came out of not wanting anybody else to mess with it. You know, [mimics shutting piano] it's done! None of thing going to 24-track. I didn't like having that many choices. didn't want that many options. I was very old-fashioned. I thought that it should be done, like, you come in and sing your song--you know your song, first of all, you know it really well. That's what Bob Dylan said: I will know my song before I sing it. And that became part of what I thought the song should be. You take it on the road and drive it so you really know it and it means something to you, and then when you sing it on record it's like taaa! You got it.

R: You evolved away from that.

TW: I think so, because I'm more, uhm...I wait now, like a spider. I can have some little piece that I want to do something with, and then I can change it and dress it up in a thousand things and then tear it down to nothing and hate it and nuke it. I love that process, where you take a song and arrange it 10 different ways. Totally refigure it. Also what happens in that type of a journey is you run into all kinds of things--rhythmic things, international borders of music where you explore rhythms and so forth. I have a good time doing it. People can go a lot places with just a brain, if they do it correctly.

R: The way you compose today, it sounds like the lyrics fall into place the way they want. Maybe the songs trust you more now.

TW: I'd like to think so. I do believe songs will come to you more if they know you've sacrificed something for them. I don't want that to sound like some kind of bullshit psychic spirituality, what I mean is...music doesn't like everybody. Everybody likes music, but music doesn't like everybody. We had a room we started recording in(5), and I was out of there the first day. I said, "I can't be here. I can't bring my songs in here." You know, you might go someplace and say, "I can't bring my friends here." Same thing with music. "I can't make music in here." Now, that's the hard part about the road. You go on the road and you have to play in the most unbelievable places. You think, "Oh my God!" That's why when I started travelling, I said I'd only be able to play nightclubs, and then only a select few. I got over it. You have to feel that the music's in you, and if you're someplace then the music will be okay. But I'm still hung up, particularly for recording, on the place where it happens. So we found a little room with a cement floor, the whole thing, and it was great. It rained all the way through the sessions, and they dragged cable down from the control booth into this little room. And then the room sounds different depending on the weather--I guess because of the air density. I'm more particular about those kinds of things, sound detail.

R: "Goin' Out West" kills. I love the line, "Tony Franciosa used to date my ma."

TW: Yeah, that's out there. I figured, let's do a rocker. We'll just slam it and scream. And my wife said, "No, this is about those guys who come to California from the Midwest with very specific ideas in mind." That's how the line about Tony Franciosa fits. There are people who come to California with less than that to go on. A phone number somebody gave them, you know, for a psychic who used to work with Ann-Margaret. "And if I meet him, maybe I can get somewhere, maybe if I play my cards right..."

R: Speaking of your missus, does she write the music with you, too?

TW: Not in the studio. We went into a room and wrote together. We came up with a list of about 60 ideas for songs, and maybe 19 will make it. We recorded more than we needed, but then you have to tell the songs, "He's strong enough to make it--but you, you'll never make it. You little shit, you'll never make it." And some of them you say, "Oh! I'm sorry, we'll fix you up, we'll make you ready. We'll try." And you fix him up and you look at him and have to say, "You're still nothing, still a little piece of shit, and you're not going on my fucking record." You have to talk to the songs that way. It scares them, but some of them really get it together. They get the message. This is the kind of military approach to recording that always works for me. There are a lot of people in medicine who are interested in music. I think you'll find more people in medicine who are interested in music than people in music interested in medicine.

R: Oh, c'mon--you toured with the Stones(6).

TW: On the other hand, I should rephrase that [laughs]. But there is a place where medicine and music overlap. I'm one of those people who can look at medical footage. I think that when you're in trouble in a movie, you should always go to medical footage. If you're lost. It kind of combs the tangles out of the audience's hair. If you've got story problems, go to medical footage. I really do have a fascination with medicine. To sum up how it compares with my process, they use instruments; there's no medical procedure that doesn't require two hands, and it's the same in music--left brain/right brain all the time; they perform in a theater; before going on, a lot of them listen to music to get fired up. And it is a show. You've got a costume, it's well-lit...

R: Sometimes there's an audience.

TW: Yup! There you go. You've got students there, and it's also filmed. They're saving lives. You know, a lot of times you go into the studio and it feels like you have to save the life of a particular song, or if it's just not gonna make it. You have to find a way. A lot of times you go beyond what you know in order to save it. You summon something other than you technique and experience. It's like the surgeon who takes off the gloves and says, "I can't. I just can't." And as he's walking away he hears: [wheezes]. Well, one more chance. So I do that to songs sometimes: "Fuck you. You never were anything. I've spent all this time and money to make you into something, and you're nothing. You'll never live around me." Then you hear the song start to rattle. "Oh, don't give up on me." Okay, we'll try. Sometimes songs make it for a week, and then they're dead. You take 'em on the road, and they just die. Other songs you keep singing, because they're riddles. You keep singing them because you never understood them, and you keep trying to understand them. So I think it's good to write songs that have puzzles for yourself, that don't necessarily have immediate meaning to you.

R: How is this album different from the others? Or is it too early to say?

TW: I hope it's very different, but I'll tell you, real departures usually require some traumatic change in your life. Something that really bends you, you know? Most times you think you're being adventuresome, but you really never left your backyard. People move in steps. Nobody grows overnight. I would like to really go out there--really out there--but I can only go a step at a time. I played a lot of percussion--I don't know if that makes it better or what. I felt better doing it myself. I guess it's up to somebody else to hear it and say what's different. Some of it's recorded at home. You didn't hear it, but I have this songs called "All Stripped Down"--kind of half-gospel, half-love song. "I want you all stripped down," but it's also about Jesus: "Can't get into heaven unless you're all stripped down." That type of thing. We recorded it at home. I have this tape recorder at home that I love so much. I recorded all these really rough tapes on it and loved the grit that I got. And I was really trying to find the same feeling in a studio. That was the challenge. I had great engineers: Biff Dawes, who I've worked with on several albums before, and Tchad Blake, who just finished working with Los Lobos.

R: You just played a benefit for the LA riots with Los Lobos(7), right?

TW: This thing just came up last minute. It was at the Wiltern Theater, at Wilshire and Western. Right in the heart of--well, Western Avenue's had a lot of teeth knocked out, so it seemed like an appropriate place to have it. Fishbone were unbelievable--just so inspiring, man.

R: Your music flourishes alongside stuff that it seems to have nothing in common with.

TW: Oh right, it's like when someone says, "You should meet so-and-so, you remind me so much of him." Why wouldja wanna meet someone just like you? If you're just like me, then I'm really gonna hate you. I never got along with myself, why would I want to sit down and talk to you? I don't know where that comes from.

R: Lazy journalism and easy record store slots.

TW: Well, popular music--whatever popular music is--there aren't very many real serious qualifications to enter that field. A lot of broken people find their way into it because nobody belongs near 'em. Time will decide what still has real value after we're gone--we're dealing with the anatomy of business and distribution. Once you get beyond that, you can maybe really hear a record and not worry about whether someone's going to think you're in or out for liking it. People today kill for tennis shoes and jackets. It's a jungle. Listening to the wrong music can get you blown in half.

R: People identify socially with pop music. I got beat up for liking punk rock in high school.

TW: That's good. It's good to have to defend what you care about. 'Cause then you can really say, "Fuck you. I don't care if you like this. I'll run you through with it. I'll cook you on this spit." It's like anybody who listens to the rap stations has known what time it is for a long while. They got all the telegraphed messages about what happened in LA long before it happened. It had been coming over the wire like telegrams, these dispatches from a very dark and disturbing place. That's all that gets out, these records. It's like jail. What I find great about rap is that most of these rap artists are guys who flunked out of English and barely made it through school, if at all. And they're using words for a living. If I were an English teacher, I would feel like I was failing instead of these kids.

R: For the benefit you played with Larry Taylor and Stephen Hodges, who were on "Heartattack and Vine" with you. They're on the new record, too.

TW: Yeah. Me and Larry and, uh, we did overdubs and all that. Ralph Carney's on there. Les Claypool from Primus. Yeah, it's mostly me and Larry. Larry's great. He used to play in VFW halls with Jerry Lee Lewis, where he would take a violin pickup and wrap it in a hanky, and drop that into the piano hole. That would be the mike. Larry would play over by that hole, and whatever came out of the speaker was the bass. He's a very intuitive musician. And right after we finished the record, his bass broke. Which I thought was great. It just couldn't take it anymore. Kind of a John Henry thing.

Notes:

(1) Frank O'Brien: originally named Frank Leroux (from Swordfishtrombones' "Frank's Wild Years"). Further reading: Franks Wild Years

(2) One from the Heart: further reading: One From The Heart

(3) Conundrum: Percussion rack with metal objects. Made for Waits by Serge Etienne. Further reading: Instruments

(4) Sometimes you find Bruce Springsteen singing to your girl: Waits had originally written "Jersey Girl" (Heartattack And Vine, 1980) for his wife Kathleen Waits-Brennan. Bruce Springsteen covered the song and made it famous.

(5) We had a room we started recording in: Prairie Sun recording studio in Cotati/ California. Former chicken ranch where Waits recorded: Night On Earth, Bone Machine, The Black Rider (Tchad Blacke tracks) and Mule Variations. Further reading: Prairie Sun official site

(6) Oh, c'mon--you toured with the Stones: Waits never toured with the Rolling Stones. He did however collaborate with Keith Richards on the albums Rain Dogs (1985) and Bone Machine (1992)

(7) A benefit for the LA riots with Los Lobos: May 30, 1992: Concert appearance for the LA Riot Benefit at the Wiltern Theatre, Los Angeles/ USA. Tom Waits: vocals, piano, guitar, bullhorn. Larry Taylor: upright bass. Mitchell Froom: keyboards. Stephen Hodges: drums, percussion. Joe Gore: guitar. Chuck E. Weiss and the Goddamn Liars, Fishbone, and Los Lobos on 'Temptation'