|

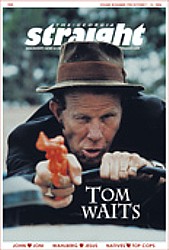

Title: Tom Waits Magazine front cover: Georgia Straight (Canada). October 7, 2004. Also printed in Aloha magazine (The Netherlands) October, 2004. Also printed in Ottawa Xpress (Canada) October 7, 2004. Date: ca. 2004. Credits: photography by Anton Corbijn |

|

Accompanying picture |

Source: Georgia Straight (Canada)/ www.straight.com. Date: ca. 2004. Photography by Anton Corbijn Source: Georgia Straight (Canada)/ www.straight.com. Date: ca. 2004. Photography by Anton Corbijn |

Tom Waits

By Jim Christy

And the rest of us, hoping for a glimpse behind the curtain at his life and the inspiration for his latest album, Real Gone, will just have to wait too.

The first listen to a new Tom Waits album is an unsettling experience. It's like walking blindfolded into a building where you've never been before. You don't know if it'll resemble a gingerbread mansion or a Motel 6. It's always midnight, and when you step over the threshold the music is going to start. And what the hell is it going to be this time?

And always, when the first selection begins, I never know if I'm in the presence of a genius or an idiot. Often, as with Rain Dogs and Mule Variations, by the time I'm halfway through the initial spin, I realize the house was built and furnished by the former. Even on the lesser albums--the last two, Blood Money and Alice, for instance--there are moments of genius and entire songs that make us reconsider everything we know about pop music.

Waits is never an idiot but always idiosyncratic. So different, in fact, that one wonders how he got that way and how he manages to do what he does. One may wonder but one can't pin him down. He eludes all pursuers. Look for him in a diner in Petaluma and he shows up at the opera in Prague. Expect a junkyard orchestra and he comes out--as in his latest album, Real Gone--with guitars and drums.

I know people of all ages who like his music. One is a 75-year-old poet who recalls phoning Tom Waits at L.A.'s Tropicana Motel back in the '70s. My friend is a noted mumbler, and Waits, well, in Sylvester Stallone's Paradise Alley, he played a character called Mumbles. So it is fitting that all my friend remembers of their conversation was mutual mumbling.

I was walking through a mall a couple of years ago with a friend's daughter, who then was seven years old. I didn't know that she had been listening avidly to Small Change, didn't know until she stopped before an octogenarian couple, he in his walker, she tottering at his side, and began to sing: "I like Shelly, you like Jane/ And what was the girl with the snakeskin's name?" As the man said, "Huh?" she continued: "Get you a little something that you can't get at home/ Get you a little something..."

So the guy's admirers aren't like other performers' admirers. I know musicians who have never heard of him and Korean schoolteachers who know all the words to all his songs. He could walk down the main street of my small town and not be recognized, but he's big in Norway.

One afternoon in 1979, I walked into the El Mocambo, a club on Spadina Avenue in Toronto, leaned against the bar, ordered a drink, and looked at the big-screen TV just as the program's host was saying, "And here he is now." And there was a lanky white guy in a mismatched suit backed by four black guys. They began vamping a jazzy number. The quartet looked straight out of 1959, all with banlon shirts under sharkskin sports coats and lacquered, stingy-brim hats. They looked like they should have been backing Jack McDuff. The white guy started to sing. He was great.

"Who is that?" I asked the bartender, who looked at me like I was straight off the trapline on my first venture to the Big Smoke. "That's Tom Waits, man!"

Tom Waits. I had thought he was some dork trying to grab a piece of Leon Redbone's market by doing a Louis Armstrong imitation.

THE FACTS DON'T tell the story. Born in California, 1949. Parents split up...father was a schoolteacher...Tom had a band in high school...worked in a pizza parlour...was a doorman at a club...got his chance on the stage...record contract soon followed...first album was 1973's Closing Time...It, and the five to follow, comprised many romantic, often even schmaltzy, songs but gems as well...Waits married Kathleen Brennan along about the time he released Heartattack and Vine in 1980...It is his first great album and signalled what was to come, 1983's thoroughly unexpected Swordfishtrombones, in which Waits metamorphosed from hobohemian to ex-carnie let loose with Brecht-Weill songs in Conlon Nancarrow's studio...Rain Dogs and Frank's Wild Years, 1985 and '87, were even stranger...Bone Machine in 1992 was another transitional album, and 1999's Mule Variations showed Waits at the top of his game, both strange and melodic, accessible without pandering to either expectations or the AM appetite...Real Gone, his latest album (of almost two dozen, including compilation and live releases), is the real goods, stripped-down mean and beautiful.

The musicians who worked on it include Larry Taylor, bass and guitar; Marc Ribot, guitar and banjo; Les Claypool, electric bass; Brain Mantia, drums; Harry Cody, guitar and bass. Waits's son Casey(1) also plays drums and works the turntables.

So there are facts about the man, but he is neither a collection of facts nor the magician fending off interviewers with his legerdemain nor the carnival talker or circus barker luring in the customers, who come out of the tent baffled and scratching their heads.

Who is he, and how did he get that way? I was under no illusions, upon being offered the opportunity to talk to Tom Waits, that I would find answers to these questions, but I thought I might catch a hint of what he is about before he hit Vancouver for two sold-out concerts at the Orpheum Theatre and the Commodore, on October 15 and 16, respectively. The publicity people for Anti Records told the Georgia Straight that I would be allowed 15 minutes. "Maybe it'll go to 20 if Jim charms Tom." I was surprised to learn later that I was granted 20 minutes. We talked, though, for 48 minutes, and we might have gone on for longer. Tom Waits was not charmed, though. He was bored, antagonistic, bristling, uptight, and only occasionally interested. But he seemed not to want to hang up, as if what was waiting for him was even less pleasant than the conversation.

I started out by commenting to Waits about the strange place he occupies in the culture, that he has taken cult to its extreme limit. He can sell out a hall in London in half an hour, the Orpheum in Vancouver in nine minutes, act alongside Jack Nicholson, and appear on the David Letterman show, yet still people can't read about him in the checkout line. His response: "Do you think I want people to read about me in the checkout line?"

I indicated that for a pop performer he was in an enviable position, with a degree of anonymity but well-known enough to sell out auditoriums and be respected by his peers. He asked: "You think maybe I should be like Liberace?"

He was not forthcoming during an attempt to engage him in conversation about Real Gone. The album is a natural progression from the rest, in one way more straightforward but, nonetheless, unpredictable. Waits's replies about the album ranged from "Uh-huh" to "I don't know."

I mentioned that despite the changes over the years, from the romanticism of the first four or so albums through the laboratory backgrounds and dark but tender lyrics of the middle work to the melding of the strains in Mule Variations and Real Gone, he has nevertheless stayed remarkably consistent to his characters, the fools and dreamers, the heartbroken and hopeful, that were there all along.

"Uh-huh."

Some of the people in Real Gone--the guy who brings back a girl to the Strip Poker Motel, the fellow in "How's It Gonna End" who "had whole dollars/a worn out car/and a wife who was/leaving for good", the "middle class girl/in over her head" in the song "Dead and Lovely", and so many others--we've met before; it's like we're catching up with them. Does she still live out on Dry Creek Road? Don't tell me Horse Face Ethel is still displaying her Pigs in Satin at the carnival. Is he still lonely in that small town? Why doesn't he get out?

Waits didn't have anything to say about any of that except "Uh-huh" or "I don't know."

The life that he presents in his work, life with all its verisimilitude and vicissitudes, reminds me of a vast canvas collaborated upon by Bosch and Brueghel and some outsider artist like Howard Finster. Did he ever view his work like that? He didn't know.

YOU CANNOT write that well unless you have read extensively, but Waits claimed not to read much. "I never finish a book. My wife can finish a book."

He did finally allow as to how he was reading two books; he went and picked them up from the floor of his bedroom or study or wherever he was. One was Riding the Elephant, he claimed, about Houdini and old-time vaudeville. Waits displayed his first flicker of interest when I told him about a new book about the death of Houdini. I could tell he was noting it down. The other book was Peter Guralnick's Sweet Soul Music. He asked me if I knew Guralnick's books. I said I had read a couple. He named the titles.

"What else do you read?" I asked.

"Nothing."

When told that was hard to believe, Waits replied sarcastically: "What, are you disappointed that I don't tell you I'm reading about the two-headed elephant?"

"You mean there's finally a book about her?"

He laughed. Well, more like a sardonic grunt.

"Dead and Lovely" on Real Gone is a movie that comes in under three minutes. It can stand alone as a poem. One line is: "And if the sky falls mark/my words--we'll catch mocking birds."

It's beautiful. I don't think there is a better poet working in English, and I don't mean just in song. Pierre Joris and Jerome Rothenberg included the lyrics of "Swordfishtrombones" in their great anthology of the best poems of the 20th century, Poems for the Millennium(2).

Still, Waits claims not to have read any of the writers I suggest to him: C�line, Rilke, C�sar Vallejo, Apollinaire, Neruda, Lorca. He's known for his interest in Kerouac and Bukowski. He put one of Kerouac's poems to music on the 1999 CD Jack Kerouac Reads On the Road(3) and based a song on Frank's Wild Years on a Bukowski story but concedes no real knowledge of either of them. He worked on Robert Wilson's play Black Rider(4) with William Burroughs; there is a BBC documentary in which he and Wilson visit Burroughs in Kansas, and Waits does a little Burroughs imitation at the end of "Circus", a recitation on Real Gone, but for all that Waits disclosed in the interview, he never heard of the guy.

But Waits was probably just unhappy or didn't give a flying you-know-what. Still, 10 minutes into our conversation I wanted to tell him to either hang up or make some sort of effort. I mean, after all, he had a job to do: talk to the press. What I did tell him was that his "Uh-huhs" reminded me of the grunt used to mark a measure in work songs--"Gonna swing that hammer down...hunh."

When he does this in Real Gone's "Top of the Hill", though more melodically, it is exactly like the Statler Brothers on Elvis's "Good Luck Charm".

He grunted sardonically again. Thus encouraged, I asked about musical influences. "Muddy Waters, Jimmy Durante, Mildred Bailey, Mabel Mercer, Dock Boggs, Jimmie Rodgers. They're some people I like. The Pogues."

Then he asked me if I knew of the late Bill Hicks.

"Check him out. He's a comedian. Has a routine called Rant in E-Minor."

We talked about how blacks and whites had influenced each other. Muddy Waters listening to Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Ballard loving the voice of Gene Autry.

We talked about old people. Waits said that as a kid he was always more interested in his friends' parents than in his friends. He used to ask them questions about their lives.

He said that he had always been interested in show business and started going downtown as soon as he was able. "I wanted to see the burlesque. Get backstage."

When told that I used to shine shoes outside the Trocadero Burlesque on Arch Street in Philadelphia, he seemed genuinely interested. "The Troc! Wow! My friend Larry Beezer(5), a comedian, has a whole routine he does about the Troc. He caught the tail end of that era. He says they had the old-time comedians and were just starting to put on movies."

"They'd have two live girls and two short black-and-white films showing girls stripping," I said. "If you stood out on the pavement, you could get a glimpse of the action through where the lobby walls didn't quite meet."

"And you were out there with your box?"

"Yeah, shoeshine box just so, so guys could put their shoes up and stare through the slit, try to catch a glimpse of something."

Waits said that reminded him of guys staring through a knothole.

He wouldn't have any of an attempt to build on that hint of conviviality, retreating back into his uh-huhs and I-don't-knows. He commented briefly on the decline of downtowns, where the old theatres and burlesque halls used to be. "People want to be under a roof. Still, you can sleep in the railroad yards if you want. It's a beautiful world. You can be anything you want to be."

As for his agenda, stage work, movies, he said he didn't know what he was going to do, if anything. When asked if there was any truth to the rumour that he would be doing an additional show in Vancouver, particularly on the October 16, the day after his Orpheum gig, he said he didn't know anything about that. (Three days later, promoters announced that Waits was, indeed, doing such a show because he likes "playing in old buildings".)

I tried to engage him in conversation about cars, but he resisted. I even asked him about UFOs, about which I'd heard he was interested. He said that anything we can't identify is a UFO, "right?"

"If it's flying, yeah."

He was not amused.

I got a genuine laugh, however, when I asked if he had been consciously imitating Lee Marvin in a scene in the 1989 movie Cold Feet where Waits leans on the bar to speaks to the bartender.

We talked about Lee Marvin and Marvin movies. "He was great. His son played drums on a couple of things on Rain Dogs."(6)

There was another spate of I-don't-knows and uh-huhs, then we got around to talking about carnivals. He asked if I had been in the carnivals, and where. I said I had, and he asked what I had done, probably checking the authenticity of my lingo.

While talking about the beloved carnival, he sighed and said, "Well, look. I'm sorry if this conversation hasn't gone the way you might have wanted."

"Not at all," I lied, saying I had admired his work for a long time and had just been hoping to get a glimpse into how it got that way.

"See, who you're talking with is the ventriloquist's dummy. This 'me' is not the real me. Only my family knows the real me. So, look, I can't always be..."

I said I hadn't wanted him to be any particular way.

"You must have expected or hoped..."

I replied that, having read other interviews, I expected him to make an end run around questions. "You come off like a boxer, dazzling the opponent with your footwork. It's a good fight plan. You divert your opponents, the interviewers, and manage to keep them at a distance and they don't even realize it. Do your rounds and hang up the phone."

Waits said I was right. "That's it exactly. You were hoping for me to talk like that? It would probably look better. I mean, are you going to have enough?"

I said I thought so, and he mentioned again about disappointing me.

"Tell you the truth," I said, "the only thing I was disappointed in was that you weren't straight-up with those questions about your reading. But I also realize that you do these things, have to do these press things, and you have all this other stuff happening in your life and it's happening simultaneously."

He said that he might have his kids around, his wife, domestic chaos, and still have to talk on the phone with someone in Belgium.

"All that stuff," I said. "Bad and good. Other business, day-to-day hassles, family things."

"You hit it there, let me tell you. Trying to manage a career and a family is the hardest thing, man. It's like taking two angry dogs for a walk at the same time and they want to go different ways."

We went on about this for a few minutes, then he said: "You wanted a glimpse behind the curtain..."

"Like at the burlesque."

"Yeah," he said. "And I'm sorry if you didn't get it."

I told him that perhaps I did.

"Yeah, maybe. Well..."

I said that we might as well end this thing.

"I guess," he said.

But he didn't hang up.

"What, Tom?"

"Uh, when I'm up there..."

"Yes?"

"Come around backstage, okay?"

Notes:

(1) Waits's son Casey: Casey Xavier Waits played on the 4-track album 'Hold On' (1999). Drums and co-writer ("Big Face Money"). The album 'Real Gone' (2004). Turntables (Top Of The Hill, Metropolitan Glide), Percussion (Hoist That Rag, Don't Go Into That Barn), Claps (Shake It), Drums (Dead And Lovely, Make It Rain). Production crew. Casey also stepped in a couple of times for Andrew Borger (drums) during the Mule Variations Tour (Congresgebouw, The Hague/ The Netherlands. June 21, 1999)

(2) Poems for the Millennium: "Poems for the Millennium, Volume 2: From Postwar to Millennium". Published April, 1998. ISBN: 0520208641 Format: Paperback, 871pp. Publisher: University of California Press.

(3) Jack Kerouac Reads On the Road: read lyrics: Home I'll Never Be

(4) Wilson's play Black Rider: further reading: The Black Rider

(5) My friend Larry Beezer: Live intro to Ol' '55 from Storyteller show, recorded April 1, 1999 in Los Angeles: "This is a song about an automobile. I had a '55 Buick Roadmaster when I was a kid. Actually, this really eh... was inspired by an old friend of mine named Larry Beezer, who... I was staying at the Tropicana Hotel, and I got a knock on the door very late and... Was that a clap for the Tropicana? Excellent! I don't think I got any new towels for the whole like nine years I was there. But I never asked, I didn't wanna upset anybody. This is about eh... What was it about again? It was about eh... It was about the car! All right, Beezer came over at about 2 a.m. He said, 'I'm on a date, and she's only seventeen, and I gotta get her back to Pasadena. And all I got left on the car is reverse.' I said, 'How can I help?' He said, 'I need gas money', and so he sold me a couple of jokes. He said, 'You can have these jokes, and you don't even have to tell folks that they're mine, cause you paid for 'em for chrissake!' And I said, 'That sounds like a good deal to me.' Anyway, he rode home, in reverse, on the Pasadena freeway. In the slow lane. I think they should give awards for that kind of thing! But anyway, it was a '55 eh... what was it? Was it a "55 Caddy?" (Transcribed by Ulf Berggren. Tom Waits eGroups discussionlist, 2000)

(6) His son played drums on a couple of things on Rain Dogs: Christopher Marvin?

- Tom Waits (1999): "My wife (Kathleen Brennan) and I wrote the songs together, arranged them and produced them in the studio with great musicians like Charlie Musselwhite, Marc Ribot, John Hammond, Larry Taylor, Greg Cohen, Andrew Borger, Smokey Hormel, the guys from Primus, and Christopher Marvin -- Lee Marvin's real son -- plays drums on Cold Water." (Source: "Wily Tom Waits' Barnyard Breakthrough" Now magazine, by Tim Perlich. Date: April 22-28, 1999)