|

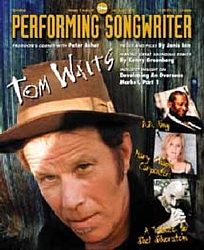

Title: Tom Waits: A Q&A About Mule Variations Source: Epitaph promo interview (MSO), by Rip Rense. Transcription as published on the Mitch Schneider Organization site. Also re-printed in "Performing Songwriter" July/ August, 1999 Date: ca. April, 1999 Key Words: Kathleen, Studio recording, Piano, Blues musicians, Studio recording, Aunt Evelyn, Testamints, Epitaph Magazine front cover:1999. Photography unknown |

| Accompanying pictures |

Tom Waits: A Q&A About Mule Variations

Tom Waits' first album for Epitaph, Mule Variations, is his first new full length studio recording since 1993. A collection of 16 pieces, it features Waits on piano, guitar, and percussion, plus musicians Larry Taylor, Dalton Dillingham III, Greg Cohen, and Les Claypool of Primus on bass; Marc Ribot, Joe Gore, and Smokey Hormel on guitars; Steven Hodges and Andrew Borger on drums and percussion; Chris Grady on trumpet; Ralph Carney and Nik Phelps on reeds; Charlie Musselwhite and John Hammond on mouth organ. Waits talked about the album, his influences, and collaboration with wife Kathleen Brennan, with journalist Rip Rense.

Q: Are you really, as the opening track declares, "Big in Japan?" How do you know this? Ever been there?

Waits: I see myself in the harbor, ripping up the electrical towers, picking up cars, going in like Godzilla and levelling Tokyo. There are people that are big in Japan, and are big nowhere else. It's like going to Mars. It's also kind of a junkyard for entertainment. You can go over there and find people you haven't heard of in 20 years, that have moved over there, and they're like gods. And then there are all those people that don't do any commercials, they have this classy image. And over there, they're hawking cigarettes, underwear, sushi, whiskey, sunglasses, used cars, beach blankets.

Q: The beginning of "Big In Japan" is one of the more startling sounds you've ever put on record.

Waits: I was in Mexico in a hotel, and I only had this little tape recorder. I turned it on, and I started screaming and banging on this chest of drawers really hard, till it was kindling, trying to make a full sound like a band. And I saved that. That was years ago. I had it on a cassette, and used to listen to it and laugh. It sounded like some guy alone in a room, which it was, trying his hardest to sound like a big, loud band. So we stuck that in the front.

Q: By the way, as an aside, that track sends my very docile, 15-year-old cat into hostile fits. He runs around, tearing things up.

Waits: Really. Therapy for him. That's a whole untapped audience. American housecats.

Q: Who wrote the Mule Variations songs?

Waits: My wife Kathleen and I collaborated on just about all of them. Of the sixteen songs that are now on the record, we wrote ten or eleven together. We've been working together since Swordfish... I'm the prospector, she's the cook. She says, "you bring it home, I'll cook it up." I think we sharpen each other like knives. She has a fearless imagination. She writes lyrics that are like dreams. And she puts the heart into all things. She's my true love. There's no one I trust more with music, or life. And she's got great rhythm, and finds melodies that are so intriguing and strange. Most of the significant changes I went through musically and as a person began when we met. She's the person by which I measure all others. She's who you want with you in a foxhole. She doesn't like the limelight, but she is an incandescent presence on everything we work on together.

Q: What prompted you back into the studio? It had been a few years.

Waits: Mainly, the only reasons to write new songs is because you're just tired of the old ones. Throw something out and get another one. It wasn't like a lightning bolt. For me, it just kind of starts with something amusing. Something amuses me, and I let it pass through my mind, along with a lot of other things. Hundreds of melodies and ideas go through your head when you're not writing. You just let them wash over you. When we start writing, we put up a little dam and start catching them. It's the old butterfly net theory.

Q: Describe the studio you work in.

Waits: It's called Prairie Sun, and it's in a small town. It's a chicken ranch out in the sticks. What's nice about it? In between takes, you can pee outside. That, for me, is the reason I keep going back. I'd say that's probably one of the more attractive qualities. In fact, they ought to put it in their brochure. That's what keeps me comin' back, that and Clive Butters(1) , who is the ranch foreman. Who is also now a member of The Boners(2) .

Q: One of the nice things about this and your recent albums is the piano sound. It sounds like a battered old upright, a practice room upright. And you can hear all the ambient squeaks and pedal noises. Probably the only record made in the last ten or twenty years where you can hear that, where it doesn't sound like a digitized concert grand.

Waits: I don't think most people notice that stuff, but I do. I appreciate you mentioning it. Pianos have to be in the right room. Most studios are designed to keep the outside world out, and they rely heavily on baffling and carpeting and all kinds of architectural devices on the wall to shape sound waves, and whatnot. I don't go in for it, myself. We've got a concrete room with a wood ceiling, and we got a great sound. We just brought the piano from home and moved it in. I gave it to Kathleen a long time ago for a birthday present. It's a Fischer from New York. We use it to catch the big ones.

Q: You commented the other day that this album is more blues-based. Some of the melodies are real simple things like "Picture in a Frame." And the ones that sound like old blues records, with the 78 scratches and hiss--- "Black Market Baby" and "Lowside of the Road." How deliberate was it to do more blues this time?

Waits: I don't know, I guess it's where I keep coming back to. As an art form, it has endless possibilities, as an ingredient or a whole meal. Definitely part of the original idea was to do something somewhere between surreal and rural. We call it surrural. That's what these songs are---surrural. There's an element of something old about them, and yet it's kind of disorienting, because it's not an old record by an old guy.

Q: What are you, about 60 now?

Waits: How'd you like a punch in the nose?

Q: The album is chock full of little stories and scenes, its remarkable how, with a suggestion or two, a line or two, you evoke a story. For example, in "Cold Water" and "Get Behind the Mule," there is one little story after another. Do you carry around a notebook and compile these little scenes?

Waits: If I forget it, I figure it wasn't worth remembering, and if I can't get it out of my mind, then I decide it must be worth hanging on to. I marvel at Leadbelly, who just seems to be a fountain of music. When he started working with Mose Ash, he told Huddie he wanted to record anything---nursery rhymes you remember, whatever. He said, get up and tapdance, and we'll put a microphone on the floor, and we'll put that on the record. And play a squeezebox, or tell a story about your grandmother. They were like concept albums. They're kind of like photo albums, with pictures of you when you're a kid. I love the way the songs unfolded, the way he would go from telling a story about the song right into the song, and there wasn't even a bump in the road when he started singing. He could have just talked for another three minutes, and that would have been fine, too. A lot of the litany in his songs were---well, he'd have a lot of repeats. 'Woke up this morning with cold water, woke up this morning with cold water. . .' It's a form. They're like jump-rope songs, or field hollers. The stuff he did with John Lomax is out on Rounder(3) right now. It's like a history of the country at that time.

Q: They recorded him tapdancing? Probably no one sounds like that anymore.

Waits: He had a strange time-step. It sounded like a Chic Webb solo. Just had a pair of old leather shoes on, and the floor of the studio. These are things that if they record today, well, you have to make sure you're not recording the bone, and throwing away the meat. It's very easily done, especially when you start thinking about it in terms of something that's going to be released. It's like the way you cook a meal alone for yourself at home is very different from when you invite seven or eight people over. I might stuff a tomato in one side of my mouth, and a piece of bread in the other, and I'm fine with that. But I wouldn't invite seven or eight people over and stuff tomatoes in their mouths, and then send them on their way, and thank them for coming. So it changes the way you feel about music, when you start recording for other people. I try to keep some of that rough-and-tumble alive when I'm recording. These other things are just as fascinating for people: what's okay for you is sometimes okay for them. So I try not to get too critical.

Q: So your process in the studio---

Waits: We go through the usual sturm and drang about it in the studio. Is this done? Or is it dead? Certain songs we'd record five different ways, and then not even use them on the record. They didn't make the cut. We ended up having to take nine songs off the record. We had 25 songs. We had enough for two records---I think, a little too much material to digest. I don't know what will happen with those songs. Probably come out in some form or another.

Q: Your writing in recent years is more succinct. You evoke more with less. Just these lines, at random, from different songs on Mule Variations: 'tend your ear to the wisdom post'. . .'found an old dog, it seems to like me'. . .'I miss your broken China voice'. . .'strangers are singing on a lawn.' . .any comment on that?

Waits: Well, I guess those are the things you try to collect and use later. Sometimes they aren't even attached to anything at all, then you start stitching them all together. You know, lines come to you all the time. People say them every day. But they're always in the context of something else. So we all say things that are fascinating without knowing it. It's like looking for interesting shapes of stones. . .like picking stuff up off the ground.

Q: Is there actually a Beulah's porch (`Fell asleep on Beulah's porch'. . .from "Take it With Me") and an Evelyn's kitchen (`I wish I was home in Evelyn's kitchen/ with old Gyp curled around my feet' from "Pony"), or are these things that just sounded or felt like the different songs?

Waits: My Aunt Evelyn died while we were making the record. She was my favorite aunt. She and my Uncle Chalmer had ten kids, and raised prunes and peaches. They lived in Gridley, and there have been a lot of times when I've been far away from home, and I've thought about Evelyn's kitchen. And I know there are a lot of people that loved them, that thought about that same kitchen. So that's why we put that in there. They had an old dog named Gyp. If you make up songs, sometimes you just get up in the morning and start singing something on the way to work. You don't know why, and maybe it's worth remembering, or maybe it's not.

Q: Ida Jane. . .Old Blind Darby. . .some of these names in Mule Variations. . .are there stories behind them?

Waits: Well, they're all real people. They all come from history, or my history. Or letters received, or things read, or half-remembered. . .or made up!

Q: Who plays the rooster on "Chocolate Jesus?"

Waits: That's a real rooster.

Q: Yes, but he was crowing right on cue.

Waits: He was crowing on cue. You know one thing about animals---when you record outside, they'll pretty much wait till you're finished with your phrase. Because no one wants to talk while you're talking, especially a rooster.

Q: Is this rooster leftover from when the studio was a chicken ranch?

Waits: It still is a chicken ranch. So if you got outside, which we did on that song---we just set up in the driveway---you use directional microphones. They look like rifles, and they use them for field recordings. The engineer found them at a flea market. So if you set up right outside with the dogs and chickens, airplanes and trucks, it's amazing how your surroundings will collaborate with you, and will be woven into the songs. So I find that a lot of times, where you're trying so hard to keep those sounds out in a studio, that it's surprising when you actually allow them in, how they become part of the tune.

Q: "Chocolate Jesus"---what is the source of inspiration? You sing 'Don't want no Abba-Zabba.'(4) Were you just tired of Abba Zabba's?

Waits: (laughs.) My father-in-law was trying to get me interested in this business venture---these things called Testamints.(5) They're these little lozenges with little crosses on them. If you're on the road, or something, and you can't worship in the way you're accustomed to, or it's during the week, you can have one of these little Testamints, and it kind of gets you right in touch with your higher power.

Q: Body of Christ?

Waits: Body of Christ. Exactly. So we just kind of took it a step further. You got your Testamints. What about your Chocolate Jesus? Melts in your mouth, not your hand. It is kind of direct. Drink this in remembrance of me. Someone might think it's blasphemous, but it's actually kind of a grassroots spirituality.

Q: To say nothing of the fact that communion wafers don't taste nearly as good as chocolate.

Waits: They don't, really. I think they ought to send the whole thing up to Flavor Management. Why those wafers? You can go through the whole seasonal thing, where you have the clove, and apple in the autumn---communion wafers with those autumn flavors: cinnamon, clove, nutmeg, ginger. You'd bring a lot more people in. You might bring a lot more people back who've left the church.

Q: "Eyeball Kid"(6) is based on the comic strip you once mentioned that your son, Casey, is a fan of?

Waits: Could he tour? Could he get Bausch & Lomb to sponsor a tour? Spends most of his days in a jar of Vaseline. Or would it be Ray-Ban? One Ray-Ban? He'd be doing the Monocle Tour.

Q: Why did you sign with Epitaph?

Waits: They are pro-artist, they're forward-thinking, and I like their taste in music, barbecue, and cars. It's a friendly place, independent label. As Wayne Kramer(7) said, 'Most of the music on the label is 160-beats per minute.' In that sense, we are probably the oldest guys over there. It's surprising how many people at the label are musicians, and are still playing gigs. Frankly, it's more like a partnership. As a business, it's a muscle car all the way.

Q: Care to comment on what inspired "What's He Building in There?" Neighbors muttering about you?

Waits: We're all, to a degree, curious about our neighbors, and we all have four or five things that we know about them. And with those things, we usually create some kind of portrait of their life. He drives that Valiant. . . Did you notice? That dog has no hair in the back. . .His wife must be sixteen. . . Look at that garage. Looks like it caught fire and he never even repainted it. . .And then you add to it, as other things unfold: I saw him last night. You ever see him wearing those lime green pants? Where's he from, St. Louis? That's the only place I've ever seen lime green pants. But he said he's from Tampa. . .And you never, ever introduce yourself. But he continues to develop like a film for you. Then you report to your wife new things every day that you've observed. His dog gets loose and comes into your yard, and has no license. We all do that, don't we? I was thinking that he's the guy. He's talking about himself. He's delusional. We've all become overly curious about our neighbors, and we all do believe, in the end, that we have a right to know what all of us are doing.

Q: Tell me about "Filipino Box Spring Hog."

Waits: That would fall in the category of surrural. Beefheart-ian. When we lived on Union Avenue in L.A., we had parties. We sawed the floorboards out of the living room, and we took the bed, the box spring, and first dug out the hole and filled it with wood, poured gasoline on it, and lit a fire. And the box spring over the top, that was the grill. We brought in a pig and cooked it right there.

Q: "Hold On," "House Where Nobody Lives," "Picture in a Frame," "Georgia Lee," "Take it With Me," "Pony" and "Come on Up to the House" are very moving songs. I don't think anything on the album is more affecting than "Georgia Lee." Can you tell me about it?

Waits: The girl's name was Georgia Lee Moses. It's been over a year. They had a funeral for her. A lot of people came and spoke. I guess everybody was wondering, where were the police, where was the deacon, where were the social workers, and where was I and where were you. Now that she's gone, one thing that's come out of it is that her neighbor has opened her home as a place where teenaged girls can come, where latchkey kids can come and hang out after school till their parents get home. A lot of kids are raising their parents. You usually run away because you want someone to come and get you, but the water is full of sharks.

Q: "Take it With Me". . .the old cliche, you can't take it with you, isn't true. Listening to this, I realized that you take a lot of stuff with you.

Waits: We wanted to take the old expression `you can't take it with you' and turn it on its ear. We figure there's lots of things to take with you when you go. We checked into a hotel room and moved a piano in there and wrote it. We both like Elmer Bernstein a lot. My favorite line is Kathleen's. She said `all that you've loved is all that you own.' It's like an old Tin-Pan Alley song.

Q: "Get Behind the Mule."

Waits: That's what Robert Johnson's father said about Robert, because he ran away. He said, 'Trouble with Robert is he wouldn't get behind the mule in the morning and plow,' because that was the life that was there for him. To be a sharecropper. But he ran off to Maxwell Street, and all over Texas. He wasn't going to stick around. Get behind the mule. . .can be whatever you want it to mean. We all have to get up in the morning and go to work. Kathleen says, "I didn't marry a man. I married a mule." And I've been going through a lot of changes. That's where Mule Variations came from.

Q: What did she mean by that?

Waits: I'm stubborn.

Q: I know you recorded a lot of songs for this record, and you had to do a lot of trimming, is it hard to make those edits?

Waits: Sometimes you have to take stuff out to let other stuff shine better. We talk about it. Flip for it sometimes. I'd like to do a record with twelve songs, but I just couldn't let go of all those songs. I didn't know which were the best songs out of 25.

Q: Tell me about "Lowside of the Road."

Waits: Leadbelly was involved in a skirmish after a dance one night on a dirt road, late. Someone pulled out a knife, someone got stabbed, and he went to jail for it. He was rolling over to the low side of the road. I seem to identify with that. I think we all know where the low side of the road is.

Q: The music on "Black Market Baby" suggests dripping water in some kind of sewer pipe. All of the songs have their own distinct atmosphere. Do these settings develop, or are they designed in advance?

Waits: You texture and layer them and turn the lights down inside the song. . .after a while, you do it by taking things away, and adding things, until you have just the right feeling for where you're going. It's like a room in your ears. It's like throwing a T-shirt over the lamp by the bedside to change the way the motel looks. Kathleen came home with "Black Market Baby." She had it almost all finished. She says, 'She's my black market baby, she's my black market baby, she's a diamond that wants to stay coal.' I thought she said cold. That was almost finished the minute that she said that. Just kind of filled it in.

Q: What's the story behind "Pony"?

Waits: Oh, I've written those songs before. You're way out far away from home. How are you going to get back? It's that kind of song.

Q: It is a recurrent idea in your work. "Shore Leave" from Swordfishtrombones, even "Shiver Me Timbers" from The Heart of Saturday Night. What were your musical inspirations, influences, before you first left home. . .

Waits: When I was first trying to decide what I wanted to do, I listened to Bob Dylan and James Brown. Those were my heroes. I listened to Wolfman Jack every night. The mighty ten-ninety. Fifty thousand watts of soul power. My dad was a radio technician during the war, and when he left the family when I was about eleven, I had this whole radio fascination. And he used to keep catalogues, and I used to build my own crystal set, and put the aerial up on the roof. And I remember making a radio on my first crystal set, and the first station I got on these little two-dollar headphones was Wolfman. And I thought I had discovered something that no one else had. I thought it was comin' in from Kansas City or Omaha, that nobody was getting this station, and nobody knew who this guy was, and nobody knew who these records were. I'd tapped into some bunker, or he was broadcasting from some rest stop on a highway thousands of miles from here, and it's only for me. He was actually broadcasting from San Ysidro near the border. What I really wanted to figure out is how do you come out of the radio yourself.

Q: Tell me about "Picture in a Frame." It's one of the more direct pieces you've done.

Waits: Simple song. Sometimes I listen to Blind Lemon Jefferson or Leadbelly, and you'll just hear a line or a passing phrase. The way they phrase something sounds like the beginning of another whole thing, and they just use it as a passing thought, kind of a transitory moment in the song. But it sounds to me like it could have opened up into another whole thing. I heard that title, "Picture in a Frame," in another song(8) . I don't even remember what the song was now. And I thought, that's a good title for a song. So I made it about Kathleen and me.

Q: Anything you want to add?

Waits: The blue whale weighs as much as thirty elephants, is as long as three Greyhound buses, end-to-end. Remember that a giraffe can go without water longer than a camel. And even though the neck is seven feet long, it contains the same number of vertebrae as a mouse's. Seven. And a giraffe's tongue is eighteen inches long. It can open and close its nostrils at will. It can run faster than a race horse and make almost no sound whatsoever. The first giraffe ever seen in the west was brought to Rome in 46 B.C. by a little guy named Julius Caesar. Something to ponder as the day winds down.

Intro by Rip Rense for the July/ August, 1999 issue of Performing Songwriter

Whenever I do an interview with Tom Waits, I wind up thinking about drainboards. Kitchen drainboards . . . It all goes back to my first meeting with him, in the fall of 1976, at the now-fabled Tropicana Motor Hotel in West Hollywood(9), where he was living. I was a police reporter for a suburban daily, and had wrangled an assignment for the entertainment page, just to break up the daily grind. I seem to remember taking the assignment because Waits' publicist represented Frank Zappa, who I really wanted to interview. If I write a piece about this guy, then maybe I can meet Zappa ...

I knew nothing about Waits. I had sort of half-listened to some of the albums that the publicist had sent: The Heart of Saturday Night, and Nighthawks at the Diner. The brand new one, Small Change, would be along in a few days. No matter ...

For the hell of it, I took a few friends along that night. (As any publicist will tell you, this is taboo.) One was six-foot-six and had an Afro the size of a tumbleweed. Another could have played linebacker for the Cowboys. We looked ... arrestable.

We made our way up the steps between the white stucco-and-wood motel bungalows, there above busy Santa Monica Boulevard, around 9:30 or 10:00 P.M. Waits was leaning against the wall outside his room under a bare white bulb, smoking. He wore pointed black boots, black chinos, and a short-sleeved shirt with the sleeves rolled up above the bicep, revealing an expansive, decorous tattoo. Three-day-old beard. A Mack cap was pulled so far forward over his face that his eyes were in shadow. I thought he looked like Henry Hull in "Werewolf of London" (who despite his lycanthropia, remained stylish in a cap). I introduced myself.

"Just woke up," growled Waits, "Come on in."

"In" was the kitchen of his bungalow, which was not quite as large as a broom closet. We sorta squeezed inside, and Waits and I sat in a couple of old wooden chairs, at an awkward angle. The other guys milled around, half-in the doorway. Waits kept glancing up at them, like he was wondering if he was about to be mugged and put in a cement overcoat. He crossed his legs, rested his elbow in one hand, and smoked and rocked incessantly. Backward, forward, rocking, rocking. Taking each drag like it was his last breath of life. I noticed that his fingers bent backward at the knuckle, in "double-jointed" fashion.

With some panic, it occurred to me that this was probably not going to be a pat interview with a dopey up-and-coming pop star. Obvious and insipid questions ("What are you working on/what inspires you") weren't going to cut it.

"Lived here long?" I ventured. (Now that wasn't insipid.)

"Uh ... a while," said Waits.

The joint was ... homey. If home was a place where you surrounded yourself with absolutely anything that interested you, in no particular arrangement. I seem to remember an automobile bumper on the kitchen counter.

"I'm thinking about putting a piano in the kitchen," he offered.

"Uh ... piano in the kitchen? Uh ... oh. Why is that?"

What is this guy talking about?

He said he just liked the idea. His delivery was marked by enigmatic pauses for head-scratching and sandpapery mumbling like, "Uhh ... well ..." and "I dunno, uh ..."

Guess I'll uh ... have to saw off the drainboard to get it in, though," he added, rocking.

What?

"Saw off the drainboard?"

He nodded, gesturing with his cigarette hand.

"Yeah. Uhh ... well .. Dunno ... Yep, gonna have to saw it off. Won't fit!"

I read articles later in which the writer referred to a piano in Waits kitchen. It was not until then that I realized that the man had not merely been attempting to discuss ... interior design. That he really did saw off the kitchen drainboard to get a piano inside.

I worked hard on that first article about Waits, especially after I listened to Small Change, and realized I had been lucky enough to meet someone highly unusual. Here, after all, was a guy only in his mid-20s (just a few years older than I was) writing melodies as durable and as wry as anything by Kurt Weill or Cole Porter, and words as impressionistic and metaphor-laden as Raymond Chandler prose. There was the whole anachronism angle, of course - drummer Shelley Manne, who played on Small Change, told me "he's like something out of the past, isn't he?" - but that didn't tell the whole story. Waits was a hipster raconteur, a bonafide craftsman, but he also had real musicianship to back it up. Played piano somewhere between Hoagy Carmichael and a late-nite whorehouse. The singing ... well, it was heartbreaking, for its substantial expressiveness and cigarette damage. You wondered whether the guy would make it to the next album; Small Change felt like the make-or-break effort of a life time. "Tom Traubert's Blues," the opening song, remains as moving, poetic, and earnest an essay about loss as has ever been set to music - and I'll include Mahler's Kindertotenlieder and anything sung by Billie Holiday in that comparison, for sheer impact.

Waits did make it to the next album, and I went on interviewing him for various publications, year after year. I admit it: I was a fan. I made writing about him a kind of mission - as I did with Zappa - to publicize a genuine original in a world overrun by music industry products and poseurs. Yet I also always found it challenging to write about him, and still do, after 22 years and a couple dozen conversations. Waits' songs force you to think, and to feel, and they acquire presence and depth with each listen.

Familiarity, in the case of this music, breeds affection, and curiosity - from the surprising tenderness of "Kentucky Avenue" (1977) to the macabre rumination of "Dirt In the Ground" (1992). I'm always thinking of things to say about his albums long after having filed the articles... For the moment, though, one of the salient things to say about Waits is that midway through his career-to-date, he changed style. The piano-bass-drums-sax-jazz/blues inflected settings mutated into something abstract. The songs became small movies; gnarled and dense short stories with Wizard of Oz endings. The "high tonight, low tomorrow" forecast of his jazz/blues period gave way to ... clouds, thunder, waterspouts, ball lightning, flash floods, and hail the size of rabbit skulls. It was a wholesale shift in climate, really, there in the country where Wait's muse lives.

Instead of telling stories in sung verse, he began framing words with haunting aural architecture, and hanging the finished works on a wall made of midnight and barbed wire. Cole porter, meet Edgar Allen Poe.

A lot of the reason for this, I believe, is Waits' undying effort to keep himself interested in his work. A lot of the reason is also his wife and often-collaborator, Kathleen Brennan, who gave him an extra pair of poet's eyes and ears.

It has been written of his new album, Mule Variations (which is being talked up as a potential record of the year), that Waits married the best of his early style with the best of his later style; that the new songs are as sonically daring as they have ever been, yet are imbued with the poignance and heart of his pure ballads. I don't know about that, but if it's true, I would say it's not by design as much as a natural outgrowth of having created art for almost 30 years, and turning 50.

I could go on and gush that the 16 songs on Mule Variations - his first album in seven years, and first for Epitaph - is as funny ("Big in Japan," "What's He Building in There?") and as thought provoking ("Picture in a Frame") and atmospheric ("Low Side of the Road") and moving ("Georgia Lee" "Take it With Me") and comforting ("Hold On") and rousing ("Come On Up To The House") and witty ("Chocolate Jesus") as his best work - or that it probably is his best work to date. But, as I say, that would be gushing.

One thing I can say with confidence is that -as with the great Zappa - the best way to write about Tom Waits is to let him do the talking. Imposing one's own thoughts, descriptions, interpretations, and witticisms on his art is like sawing off a drainboard to get a piano in the kitchen. It works, sort of, but isn't it better just to put the damned thing in the living room?

Notes:

(1) Clive Butters:Ranch foreman of Prairie Sun recording studio in Cotati/ California (former chicken ranch where Waits recorded: Night On Earth, Bone Machine, The Black Rider (Tchad Blacke tracks) and Mule Variations). Further reading: Prairie Sun official site.

Also credited on The Black Rider ("Boots" on Russian Dance) and a member of the improvised unprofessional percussion group "The Boners" (formed during the recordings for Bone Machine: Tom Waits, Kathleen Brennan, Joe Marquez and others).

- Tom Waits (1999): "Clive Butters, who is the ranch foreman (Prairie Sun). Who is also now a member of The Boners." (Source: "Tom Waits: A Q&A About Mule Variations", by Rip Rense. Date: ca. April, 1999. Also re-printed in "Performing Songwriter" July/ August, 1999)

(2) The Boners: Improvised unprofessional percussion group, formed during the recordings for Bone Machine (Tom Waits, Kathleen Brennan, Joe Marquez, Clive Butters and others).

(3) The stuff he did with John Lomax is out on Rounder: "The Alan Lomax Collection is an unrivaled assemblage of international field recordings, matchless in both sound quality and choice of performers and material, that anthologizes the work of the twentieth century's foremost folklorist, Alan Lomax. The Collection begins with Lomax's first field trips with his father in the penitentaries of the American South in the 1930s, and follows his journeys throughout Haiti in 1936 and 1937, Great Britain, Italy and Spain in the 1950s, his subsequent trips throughout the American South in the late 1940s and again in 1959 and 1960, and his visits to the islands of the Caribbean in 1962 and 1967. Many of the radio shows and concerts produced by Alan Lomax are also included in the Collection, from his pioneering BBC music programs to the hit Midnight Calypso concerts at New York's Town Hall." (Source: Rounder Records, 2004). Further reading: Alan Lomax Biography, Alan Lomax Archive website

(4) Abba-Zabba: American candy bar manufactured by Annabelle Candy Co., Inc. Further reading: Annabelle Candy official site

(5) Testamints: further reading: Testamints (official site). Read lyrics: "Chocolate Jesus"

"Testamints share a message and they freshen breath"

(6) Eyeball Kid: further reading: The Eyeball Kid

(7) Wayne Kramer: another old goat on the Epitaph label. Further reading: Wayne Kramer official site

(8) I heard that title, "Picture in a Frame," in another song: unknown/ unidentified song

(9) At the now-fabled Tropicana Motor Hotel in West Hollywood: Further reading: Tropicana Motel.