|

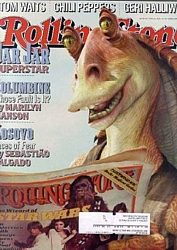

Title: The Resurrection Of Tom Waits Source: Rolling Stone magazine (USA), by David Fricke. Photography by Mark Seliger, M. Ferguson/ Galella Ltd, Chapman Baehler Date: Washoe House/ San Francisco. June 24, 1999 Key Words: Mule Variations, Testamints, Music Business, Napoleone's, Kathleen, Fish in the Jailhouse Magazine front cover: Rolling Stone. June 24, 1999 |

The Resurrection Of Tom Waits

For Mule Variations, his first record in six years, Tom Waits rounded his multiple personalities - barfly poet, avant-garde storyteller, family guy - and came up with the biggest hit of his career

by David Fricke

You know what I'm big on? Strange and unusual facts, Tom Waits says, flipping through the pages of a crumpled notebook filled with bursts of serpentine scrawl that he has pulled from his back pocket. Waits should be gabbing about Mule Variations, his first album of new songs since 1993 and his debut, after long spells with Elektra and Island Records, on the independent Epitaph label. Instead, the forty-nine-year-old singer and composer - dressed in ranch-hand denim, with brown dirt encrusted on the left shoulder of his jacket - takes a moment to decode his handwriting, then looks up with a lopsided grin.

Did you know there are more insects in one square mile of rural earth than there are human beings on the whole planet? Waits asks in the warm, lumpy growl that, with a few extra notes, doubles as his singing voice. Most dangerous job? Sanitation worker. There are 35 million digestive glands in the human stomach. Waits turns to the blackboard menu in Washoe House, a nineteenth-century roadhouse that is a short drive from Waits' home in the verdant California farmland north of San Francisco. What did you order - the club sandwich? You're gonna need all those glands.

When he finally starts talking about the fantastical blues and spectral ballads on Mule Variations - about his songwriting and the autobiography embedded in his stories - Waits still sounds like he's reading weird-science entries from his notebook. Take, for example, Chocolate Jesus, a hobo-string-band stomp about religious icons that literally melt in your mouth.

My father-in-law has, over the years, tried to get me interested in certain business propositions, he says. One of them was Testamints(1): These lozenges, they got a little cross on 'em and a Bible saying stamped on the back. Unable to worship? Have a Testamint, Waits says, his face so deadpan you're tempted to ask for a stock prospectus. So Kathleen and I - referring to his wife, co-songwriter and co-producer, Kathleen Brennan - just took it out: 'What is he trying to get us involved in? What's next? A chocolate Jesus? '

The riotous field holler Filipino Box Spring Hog is, Waits claims, based on the queer cuisine and mad guests ( Rattlesnake piccata with grapes and figs/ Old brown Betty with a yellow wig ) at rent parties he used to attend. And the vacant piece of real estate in House Where Nobody Lives a country-soul weeper about how love, not decor, makes a home - was inspired by a place not far from Washoe House.

It had busted windows, weeds, junk mail on the porch, Waits says, It seems like everywhere I've ever lived there was always a house like that. And what happens at Christmas? Everybody else puts their lights up. Then it looks even more like a bad tooth on the smile of the street.

This place in particular, he goes on, everybody on the block felt so bad, they all put some Christmas lights on the house, even though nobody lived there.

Waits stops for a gulp of his split-pea soup. I'm just like everybody else, he admits. I'm nosy. If I know three things about my neighbor, I take those, and that's enough for me to go on. And what he doesn't know doesn't stop him: Everybody mixes truth and fiction. If you're stuck for a place for a story to go, you make up the part you need.

Waits wags his notebook in the air as if to suggest that his most outrageous Mule inventions - Eyeball Kid, a guy who is all cornea and smarm; the mystery recluse in the creepy spoken-word piece What's He Building? ( He has no dog, and he has no friends, and his lawn is dying.... And what about all those packages he sends? ) - are only as twisted as life itself. Songwriting, he says, is not a de deposition.

Waits is standing in a record store down the road a piece from Washoe House holding a Japanese import CD by Rage Against the Machine that he's just bought for his thirteen-year-old son, Casey. He'll think I'm really cool for getting him this. , Waits says proudly.

Everybody mixes truth and fiction. If you're stuck for a place for a story to go, you make up the part you need.

He looks at the store racks packed with CDs. It's gotta be hard for someone starting out now, Waits remarks, a bit sadly. All the business you have to go through, making the videos, all this competition. He waves a hand at the mass of music in front of him. I thought it was bad when I started out.

That was in 1973, the year Waits issued his debut album, Closing Time - a collection of hard-luck and bruised-love songs, soaked in Johnny Walker Red and Johnny Mercer chord changes, released in the thick of glitter rock and arena boogie. I'm on the wrong end of the wheelbarrow every time, Waits notes with a gritty laugh.

Waits has spent much of the Nineties disengaging himself from the grind of what he drolly calls this business we call show. His last major tour was more than ten years ago, documented on the 1988 live record Big Time. You can count the albums he's issued since then on one hand: 1992's Bone Machine and the soundtrack to the Jim Jarmusch film Night on Earth; Waits' score for The Black Rider, his 1993 theatrical collaboration with Robert Wilson and the late William S. Burroughs; the anthology Beautiful Maladies: The Island Years.

I see what you mean, Waits concedes. It's like looking for your waitress. People get like that with artists. We are a product-oriented society. We want it now, and we want an abundance of it in reserve.

But there are limits to what you can do. One is not a tree that constantly blooms in the spring; the fruit falls and you put it in a basket.

As an Epitaph artist, Waits is no further from the mainstream than he was as a major-label act. Of the fifteen records he made for Elektra and Island, only Small Change (1976) and Heartattack and Vine (1980) cracked the Top 100. Waits' deal with Epitaph, the indie-punk imprint founded by ex-Bad Religion guitarist Brett Gurewitz, only covers Mule Variations. But Waits says he already plans to re-sign: They're easier to be around than folks from Dupont. Not to generalize about large record companies, but if you're not going platinum, you're not going anywhere.

Ironically, Mule Variations - which debuted at Number Thirty on the Billboard 200 - is Waits' most commercially accessible record in years. It is actually three records in one, a vibrant survey of a restless talent often compartmentalized on concept albums, Big in Japan, Get Behind the Mule and Chocolate Jesus are all cut from the Brecht-does-Leadbelly crust of Waits' mid-Eighties classics, Swordfishtrombones and Rain Dogs. The deathbed dada of Bone Machine is cranked up to comic effect in the guitar-and-toolbox clatter of Eyeball Kid and Filipino Box Spring Hog.

And in Hold On and House Where Nobody Lives, Waits returns to the Gin Pan Alley romanticism of Closing Time, Small Change and his cult breakthrough LP, 1974's The Heart of Saturday Night. I wasn't very adventurous, Waits says, explaining why he ditched the genteel-beatnik act in the Eighties. Most people, when they start out, are much more adventurous. As they get older, they get more complacent. I started out complacent and got more adventurous.

But Waits' early, barroom-piano diamonds - Ol' 55, (Looking for) The Heart of Saturday Night, Drunk on the Moon - were the product of sincere research. Born December 7th, 1949, in Pomona, California, the son of a Spanish-language teacher, Waits has, since adolescence, been fascinated with the surreal properties of real life. When I was fourteen, he says, I worked in an Italian restaurant in a sailor town(2). Across the street was a Chinese place, and we'd trade food. I'd take a pizza to Wong's, they'd give me Chinese food to bring back. Sometimes Wong would tell me to sit in the kitchen, where he's making all this food up. It was the strangest galley: the sounds, the steam, he's screaming at his co-workers. I felt like I'd been shanghaied. I used to love going there.

Later, when he started touring, Waits made a point of avoiding standard rock-star hotels. I'd get into a cab at the train station, he says, and pick an American president. I'd tell the driver, 'Take me to the Cleveland.' Invariably, there would be a Cleveland.

I would wind up in these very strange places - these rooms with stains on the wallpaper, foggy voices down the hall, sharing a bathroom with a guy with a hernia. I'd watch TV with old men in the lobby. I knew there was music in those places - and stories. That's what I was looking for.

By the end of the Seventies, Waits had burned out on the stew-bum-bard routine. I felt like one of those guys playing the organs in a hotel lobby, he says, making the boom-chicka-chicka sound of a cheesy rhythm machine for emphasis. I'd bring the music in like carpet, and I'd walk on it. My wife, she's the one who pushed me. Finding a new way of thinking - that came from her.

Waits and Brennan met in 1980. He was in a small office at Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope studios, working on the score for One From the Heart. She was a script editor at Zoetrope. He was listening to Captain Beefheart, Howlin' Wolf and Ethiopian music. She encouraged him to take more risks in his writing - to, Waits says, distort the world. After they were married, Waits made Swordfishtrombones. It was interesting, he says. My life was getting more settled. I was staying out of the bars. But my work was becoming more scary.

I'm the kind of bandleader who when he says, Don't forget to bring the Fender, 'I mean the, fender from the Dodge.

Brennan declined to be interviewed for this story. Waits, too, is privacy-conscious; he is politely sketchy about his personal life, the location of his home and the couple's three children, Casey, Kellesimone and Sullivan. But he talks about how he and Brennan work together - with a rented piano in a local hotel room - and describes co-writing as a sack race. You learn to move forward together. Example: Brennan had some lines - I got the style/ But not the grace/ I got the clothes/ But not the face. Waits had an old tape he'd made of himself beating a jungle-telegraph rhythm on a chest of drawers. The result: Big in Japan.

Fish in the Jailhouse,(3) written for but not included on Mule Variations, came from a dream Brennan had one night: that she was in prison and an inmate was singing about how he could open any jail door with a fish bone. It kind of became a swing tune, with a big backbeat, Waits explains, then belts out a verse in his gale-force howl: Peoria Johnson told Doug Low Joe/ 'I can break out of any old jail, you know/ The bars are iron, the walls are stone/ And all I need me is an old fish bone'/ Servin' fish in the jailhouse tonight.

I went through a period where I was embarrassed by vulnerability as a writer things you see, experience and feel, and you go, 'I can't sing something like that. This is too tender.' Maybe I'm finding a way of reconciling that, he says of Mule Variations. I'm married, I got kids. It opens up your world. But I still go back and forth - between deeply sentimental, then very mad and decapitated. Waits grins. I live with a bipolar disorder.

If you can't understand why Waits has stayed off the road for the last eleven years, only giving sporadic concerts and appearing at benefit shows, concerts and appearing at benefit shows, consider this list: Redd Foxx, Blue Oyster Cult, Richard Pryor, Big Mama Thornton, Bette Midler, Fishbone, Link Wray, the Persuasions, Frank Zappa and Howdy Doody. Those are just a few of the acts Waits opened for in his character building travels in the mid-Seventies.

Zappa - that was my first experience of rodeos and hockey arenas, he says, shaking his head. The constant foot stomping and hand clapping: 'We! Want! Frank!' It was like Frankenstein, with the torches, the whole thing.

The gig with Fifties TV star Buffalo Bob and his marionette, Howdy Doody(4) , was a double whammy: at 10 A.M., in front of housewives and kids. I wanted to kill my agent. And no jury would have convicted me, Waits says, only half-kidding. Bob and I didn't get along. He called me Tommy. And I distinctly remember candy coming out of the piano as I played.

Jesus, he sighs. That's when you need the old expression, 'You gotta love the business.'

Waits feels no great need to love the business anymore. He will give a few concerts to promote Mule Variations; he taped an edition of VH1's Storytellers(5). But Waits will not tour. Every night, you sing the songs, he muses. How do you do that without feeling you're hitting them real hard with a hammer, until they're flat?

He is quite happy with the shadowy, personalized space he inhabits in popular music, way off Celebrity Highway. Waits' work is critically respected; his songs have been covered by Rod Stewart, Bruce Springsteen and the Ramones, among others. He participates in outside projects of exquisite taste and eccentricity: a tribute album to the late Moby Grape singer and guitarist Skip Spence; the recent experimental-music collection Orbitones, Spoon Harps & Bellowphones, to which Waits contributed Babbachichuija, (6) a composition for squeaky doors, a 1982 Singer sewing machine and a washer set on SPIN CYCLE. I'm the kind of bandleader, says Waits, a keen student and collector of bizarre instruments, who when he says, 'Don't forget to bring the Fender,' I mean the fender from the Dodge.

Waits also has a burgeoning second career, as a character actor, playing the same kind of colorful nuts and drifters who pass through his songs. He recently finished work on Mystery Men, a comedy starring William H. Macy, Ben Stiller and Geoffrey Rush, in which he portrays a weapons designer for a gang of hapless superheroes. I make something called a Blamethrower, Waits explains. You aim it at people and they start blaming each other. 'It's your fault!' No, it's your fault!' It's a nutty movie.

There's something to be said for longevity, Waits says of his career. For some people, being in pop music is like running for office. They court the press in a very conscientious fashion. They kiss babies. No matter how black their vision is, their approach is the same.

I'm more in charge of my own destiny, he insists. And the music, the stories, the weird shit he writes in his notebook for future reference they're always there, waiting for him, no matter how long he goes between records. The songs are coming all the time, he says. Just because you didn't go fishing today doesn't mean there aren't any fish out there.

So you don't want to fish for a couple of weeks, a couple of years? Waits adds with a subterranean cackle. The fish will get along fine without you.

Notes:

(1) Testamints: further reading: Testamints (official site). Read lyrics: "Chocolate Jesus"  "Testamints share a message and they freshen breath" (2) I worked in an Italian restaurant in a sailor town: further reading: Napoleone Pizza House

"Testamints share a message and they freshen breath" (2) I worked in an Italian restaurant in a sailor town: further reading: Napoleone Pizza House

(3) Fish in the Jailhouse: released on Orphans in 2006. Read lyrics: Fish In The Jailhouse

(4) Buffalo Bob and his marionette, Howdy Doody: First mentioned in the self written press biography for The Heart Of Saturday Night (1974). Howdy Doody (w. Buffalo Bob, born Robert Schmidt on November 27, 1917) was one of the first American television shows for children. In 1947, NBC brought The Howdy Doody Show to television sets across the US. The TV show went off the air in 1960. From 1970 to 1976 Howdy Bob toured with his show and made hundreds of appearances across the US. May 1-6, 1973. The Great South East Music Hall & Emporium. Atlanta, Georgia/ USA. Further reading: Performances

(5) An edition of VH1's Storytellers: April 01, 1999 VH-1 recordings for the Storytellers' special. Burbank Airport. Los Angeles/ USA. The show aired May 23, 1999. Further reading: Performances

(6) Babbachichuija: freeform singing "Orbitones, Spoon Harps & Bellowphones". Ellipsis Arts, 1999. Read lyrics: Babbachichuija