|

Title: Son Of A Gun, We'll Have Big Fun On The Radar Source: New Musical Express magazine (UK), by Bill Foreman. Thanks to Kevin Molony for donating scans Date: January 10, 1987 Key words: Down By Law, Jim Jarmusch, John Lurie, Filmmaking, Roberto Benigni Magazine front cover: New Musical Express. January 10, 1987 |

| Accompanying pictures |

Son Of A Gun, We'll Have Big Fun On The Radar

Long-time cig-chomper, piano man and barfly Tom Waits has just made another cinema appearance, in Down By Law, directed by Jim Jarmusch. Bill Foreman interviews director and star about the mechanics of black and white moviemaking and how to succeed as the Prince of Melancholy.

"Sorry I wasn't around earlier, I was, uh, bitten by a rattlesnake." The corrugated voice and hyperactive imagination belong to Tom Waits, a man whose talent for free-association could send a herd of psychiatrists back to their textbooks. Seahorses, bad reputations, motel suites, spies, condensation, men's assistance centres, high fashions and low, low prices all swim amicably in Waits's stream of consciousness, but he's aware that reality can be less colourful.

"That's why people make up these little stories, in order to escape into them sometimes," says the acclaimed song-writer now actor. 'You become impatient with your life and so you find these little places where you can move people around, change their names and, you know, alter things a little bit."

In Down By Law, Waits finds himself in the position of his own characters, delegating a measure of his free will to 33-year-old writer/ director Jim Jarmusch. Cast in the role of Zach, a down-and-out DJ, Waits winds up in a Louisiana prison cell with a pimp (played by Lounge Lizards leader John Lurie, who also starred in Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise) and a wide-eyed tourist (played by Italian comedian Roberto Benigni). The prematurely silver-haired Jarmusch says the characters are based on the actors themselves, but only to a limited extent.

"I try to take things from my perception of their personality - which may not always be right - and put it into the character," says Jarmusch. 'But I also try to eliminate parts of their personality that don't fit the character. So it's never like, okay, this is a role where John Lurie can just be John Lurie. It doesn't work that way. John Lurie has to suppress certain parts of his personality that don't fit the character.

"It's obvious in the case of Tom Waits that the character he portrays is not really Tom Waits. It's Zach, it's someone that has different obsessions and different responses to people. But there is a strong element of Tom Waits in that character. It was actually Tom's idea that he should play a DJ. In my first draft, I had him as an unemployed musician, but I always felt that was too close to Tom, and so did he."

Dr. Sullen and the silent DJ

"I've been making fun of those guys for years," says Waits in reference to Lee baby Sims(1), his character Zach's on-air handle. "Lee baby Sims is a real guy that I used to hear in Rapid City. He's one of those kinda gypsie DJs that moves around a lot. Those guys live like Fuller Brushmen, change their name, leave town, set up somewhere else, live in hotels. So it's just a voice from my youth I remember.

"I like the way Jim approaches filmmaking," says Tom of the director, who, unlike Jarmusch's friends Susan Seidelmen and Alex Cox, keeps his set closed to visitors. "I consider Jim more a lonesome filmmaker than an independent filmmaker. Lonesome Jim Jarmusch." Tom laughs. "It's a real social activity, so you really have to be simple-minded about what you want. Reorganising details of behaviour - it's a pretty insane thing to be doing, I guess." Waits is not entirely a social animal himself, and admits to trusting few people apart from his wife (Kathleen Brennan, with whom he writes songs) when he comes to full collaborations. His previous film appearances (in The Cotton Club, Rumble Fish, The Outsiders, Wolfen and Paradise Alley) were mostly limited to a few lines, and he remembers being real nervous and wanting to back out of Down By Law. But once on location in New Orleans, Waits regained his confidence. 'It was Dr Sullen [Waits' name for Jarmusch], Bob Angeles [Benigni], the Great Complainer [Lurie], and I'm the Prince of Melancholy. For me, it was like once we got there, it started to feel like something was gonna happen, you know?"

Dr Sullen and the Prince of Melancholy met, by Jarmusch's recollection, at a going away party for John Lurie on the eve of a Lounge Lizards European tour. "It was put on by this friend of ours who was a painter(2), and he invited a lot of people like Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger. And Wim Wenders was there, because he was in town and we told him to come. [Jarmusch apprentices with the German filmmaker on Lightning Over Water, while Down By Law director of photography Robby Muller has worked on several other Wenders films.] I don't really much enjoy that kind of thing with celebrities hanging around. I'm still kind of shy, and Tom seemed to be sort of in a corner also. And I just kind of ended up being in that corner with him." The director recalls mixed first impressions of his future star. "He was sort of shy and guarded, and yet had an incredible sense of humour. His use of language, just in conversation, is really amazing." Jarmusch who was already a fan of Waits' music, was soon to be impressed by this acting. The director raves about Waits and his wife's theatrical production, Frank's Wild Years, which he saw three times during its run in Chicago, and says he was impressed by Waits' grace in subtly unfolding the character of Zach in Down By Law. "We form an impression of him at the beginning that we slowly let go of by the end of the film, because we know that character differently. And I think that, as an actor, that's something very delicate and not so easy to do. Jarmusch suggests that the contradictions in Waits' character Zach, a DJ who doesn't like to talk but does it for a living, remind him of the artist himself. "He's contradictory in certain ways. I mean, his personality is very strong and his opinions and thinking are very clear, but he's very careful before he responds to something. He thinks things through before he says what he feels about something. But he can also have a hot temper. "He's somebody who's very tough and very gentle at the same time. He doesn't really stop between those two poles. He's always shifting back and forth between them. It makes me like him a lot."

Jarmusch says he personally feels more comfortable with musicians than film people, a preference that dates back to hanging around New York clubs like CBGB's(3), catching shows by the Rotating Power Tools (who would become the Lounge Lizards) and Talking Heads (for whom he would direct 'The Lady Don't Mind' some ten years later). The director tried his own hand at music in a band called the Del Byzanteens, who released an EP and album on Britain's Beggar's Banquet. "I played keyboards and vocals and did some kind of strangely - tune guitar playing," he recalls. "The keyboards were often tapes treated through synthesizers - very crude stuff... The band kinda took a strange turn and was less interesting when we did our album, and I don't think it worked very well. But the EP I still like." Jarmusch and one former Byzanteen are planning to record another EP, which promises to sound like "Bo Diddley goes to Istanbul or something." As for Waits, he's rearranging songs from Frank's Wild Years for an upcoming album, trying to make them work on their own without visual assistance. "It's hard to get them to all walk around in the same shoes," says Tom, "so it's all in one piece and consistently mad in it's own way."

Down on the Bayou.

After grappling for the right word, Jeffrey Lyons and Michael Medved, the unfortunate filmcrit duo from America's Public Broadcasting Service, decided "goofy" was really the only word to describe Down By Law. This of course comes from the same mouths that pronounced Blue Velvet "putrid", and joyfully suggested you dress up before going to see the Cannon Films version of Othello. The pair also warned that many Down By Law scenes are just too long. But those of us less concerned with wearing tuxedos to opera films will appreciate Jarmusch's talent for taking a scene to the point where it appears played out, and then going considerably further to reach unpredictably marvelous results. His pacing, combined with his spectacular use of black and white film in both Stranger and Down By Law, has made Jarmusch the sort of director pop film critics like to call "offbeat". And while he frequently devises "oblique strategies" (like having every scene in Stranger Than Paradise be a single shot) that gives his work an original style, there is much about his films that has, despite the minimalism, a classical feel. "All of my films take place in that present, but they have a look that suggests other decades, and that's certainly intentional, " Jarmusch acknowledges. "Hopefully they make it not that obvious to the audience, so they just slip into it as an imaginary world that is not very obviously taking place right now. I mean, black and white does that by nature for people. And I'm certainly not interested in the current TV language of editing, that kind of rhythm of films and language of close-ups that tells you, 'This is dramatic, so now we have a close-up'.

Down By Law doesn't fit into a Miami Vice style of filmmaking, this kind of MTV disease that seems to be infiltrating everything. "So we can assume Jarmusch doesn't confer regularly with Michael Mann. "Well, see, I'm not saying that that's garbage. It's just not my style. I couldn't make a film that way, because I don't think that way. So people who do work that way, I don't look down on them or feel that my way is better. But I'm not about to imitate their way because it doesn't come naturally. "It does annoy me also," he admits, 'because I think that when you watch that style of film, you're being treated as though your attention span is only six seconds long. I think that's condescending to the audience. 'It's not that I don't like things that are quick cut, because there are lots of great filmmakers that use that style, especially the early Soviet film directors like Eisenstein and Vertof. They use that machine gun style of editing sometimes that's really effective, really beautiful. It's just how you employ things." Though less radical in its departure from film convention than Stranger Than Paradise, Jarmusch's "prison film" was subjected to its own set of oblique strategies. There are no cutaway shots and, in an effort to keep audiences from associating with any single character, there are also no point of view shots. In order to keep all his characters within the frame and in focus, Jarmusch relied almost exclusively on a 25-millimetre lens, the same type used by Japanese director Ozu, whose regimented camera techniques so influenced Wim Wenders that he filmed a documentary on them. "Ozu used to use only two camera positions, as you know from that film," says Jarmusch. "We were not that rigorous, but we did use a 25-millimetre lens for almost the entire film, because we needed to have deep focus in a lot of scenes... If we had used a lens that was any wider, it'd start to distort. It's actually a beautiful lens, the 25." As is Jarmusch's continuing use of black and white, which these days is more expensive to use than colour. "I had a lot of trouble getting good prints," says the director, "because most of the black and white technicians are retired. And young lab technicians don't really know black and white, they're not trained."

Film costs notwithstanding, Jarmusch's black and white characters are still inexpensive by today's standards - Stranger came in under $200,000 and Down By Law held the line at a million. The director doesn't imagine his next film could cost more than two or three million at most, which means he may continue to finance his projects outside the Hollywood studio system. "I'm spoiled in a way, but I'm in a good position right now. I'm very lucky that there are ways I can finance my next projects without having a studio tell me who to cast and how to cut my film and what kind of music to use. So if that were the only way they wanted to finance the project, I'd walk." But Jarmusch says he has been courted by a number of major studios. "I've only been meeting them to see what they say, to see intuitively how I feel about people specifically... I don't care where the money comes from, I just don't want businessmen telling me how to make my films." The director concedes that a Hollywood studio might have pressured him to scrap Down By Law's opening sequence, tracking shots of New Orleans neighbourhoods that, while striking, are sometimes blurred, "It's something very strange that happened that we still don't know technically how it happens, "Jarmusch admits. "When you shoot something flat on, as opposed to passing something at an angle, you get this kind of aberration. We did tests and everything to try and figure it out, and it wasn't the lenses. It might have had something to do with aeroflex cameras, although we're not even sure of that I kept them." Jarmusch laughs. "I should probably lie and say, Yeah, we intended to do that."

Jarmusch's use of music in films is nearly as individual as his approach to filmmaking itself. Down By Law, in addition to its soundtrack of avant-garde atmospherics by John Lurie and raspy songs by Tom Waits, also features a touching scene in which two characters dance to a jukebox playing Irma Thomas' classic New Orleans ballad 'It's Raining'. Likewise, in Stranger, Jarmusch used Screaming Jay Hawkins' 'I Put A Spell On You' as a recurring theme. "I don't have a specific song for the next film that I'm making, but there will be one," says Jarmusch. "It seems like people use music, especially pop songs, in films these days to drive a sequence, something that's not really important in the film. And instead I use them with very static shots, and let the song really interact with the characters, the way that people listen to music." Jarmusch's eye for detail and careful approach to each scene can be credited to the influence of director Nicholas Ray(4), who collaborated on Wenders' Lightning Over Water, Jarmusch's first notable film credit. "I learned from Nick about constructing a film in an architectual way, about talking and working with actors, and the fact that every scene has to have one essential meaning for you, the director or writer. And if every scene works as a single idea, then the film will work." Down By Law does work beautifully, and Tom Waits knows why: "It's a fable. I think to understand that. With Bob Benigni, you know, God protects dogs, fools and little children. Whereas Zach and Jack are cynical, plotting, low-rent, smalltime, chickenshit little guys. You know, they treat their women badly, they're walking around in the dark. "The character of Jack," Waits continues, "has a bad temper, he's a stick of dynamite. He's a refrigerator. He's like a bad detective. He's a pimp in the woods. Bad table manners, uptight, self-centered, well-dressed, bad attitude. He's like an old cigar." But Benigni's Italian tourist, says Tom, is like an angel, and it is he who finds his rewards here on earth. "Benigni is filled with hope, you know? He takes off his hat and all the birds fly out of his head. He still believes in songs and things he saw in movies. He walks between the raindrops. So all things come to him, he's a force of nature, he's like a magnet. It's like we scare all the birds away and Benigni puts little crumbs out and they all land in his lap... And you gotta hope you have a little bit of Bob Benigni in you, you know?"

Notes:

(1) Lee baby Sims: Lee "Baby" Sims on KCBQ (San Diego, 1970), WPOP (Manchester, CT), WCSB FM (The Lee Baby Sims Show, Cleveland State University), KONO FM (San Antonio). Also passing mention of this fictional Waitsian character in Salman Rushdie's "The Ground Beneath Her Feet".

(2) This friend of ours who was a painter: That would have been Jean Michel Basquiat November 1984.

- John Lurie: "Jean Michel Basquiat was a really good friend of mine, probably my best friend at this particular time and my band was about to go on tour so he throws this dinner party for me. Now, at the dinner party was Andy Warhol, Steve Ribel, Bianca Jagger, Julianne Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, Wim Wenders, Tom Waits, Jim Jarmusch and like 30 other people - everybody's a heavyweight in some area. This party was just a great party. So, Andy Warhol writes in his diaries that this party was THE BEST PARTY he's been to in, like, 5 or 10 years and he was going to stop hanging out with faggots and start hanging out with artists because they are just so much more elegant and interesting. Now, the woman who transcribed his goddamned diaries turned me and Tom Waits into - John Waite - . Do you realize a person could retire from nightlife FOREVER if Andy Warhol said your party was THE BEST PARTY he's been to in 10 years!! I really got screwed, boy. Her name's Pat. If you put her in the article, misspell Pat."(Source: Rebirth of the Cool - the Toast chat with John Lurie of the Lounge Lizards by Melissa Maristuen. Toastmag).

- "Andy Warhol Diaries" - Author: by Pat Hackett (Editor) Warhol dictated his diary to Pat Hackett at 9:30 am daily from whereever he was in the world. It started out as an expense account diary, but evolved into a chronicle of the wild times in the Warhol world of the 70s and 80s. The book is edited from original 20,000 diary pages. Andy Warhol: "Cabbed to Mr. Chow's (restaurant) for Jean-Michel's party. And it was great. I feel like I wasted two years running around with Christopher and Peter, just kids who talk about the Baths and things, when here, now, I'm going around with Jean-Michel and we're getting so much art work done, and then his party was Schnabel and Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch who directed "Stranger Than Paradise" and Clemente and John Waite who sang that great song, "Missing You." I mean, being with a creative crowd, you really notice the difference. It's intriguing both ways, and I guess both ways are right, but ..." (Source: Andy Warhol on Jean-Michel Basquiat, November 14, 1984. Excerpts from the Warhol Diaries).

(3) CBGB's: New York club located at 315 Bowery in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. For further reading try the official CBGB site. TW: "I was on the Bowery in New York and stood out in front of CBGB's one night. There were all these cats in small lapels and pointed shoes smokin' Pall Malls and bullshitting with the winos. It was good." (Source: Tom Waits: The Slime Who Came In From The Cold, Creem magazine (The Beat Goes On) by Clark Peterson. March, 1978)

(4) Nicholas Ray: Waits too was inspired by this director's movies.

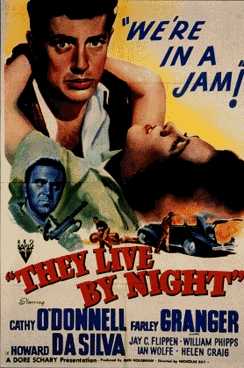

- Brian Case (1979): "Did he get "Burma Shave" from the Nick Ray movie, They Live By Night, from 1947?. TW: "Yeah, that's the one. In fact that's a great story. Very sad at the end where he gets mowed down at the motel. Farley Granger does soap operas now, I think. He was in Minneapolis and this woman disc jockey played it for him and he got a real kick out of it. He always played the baby-faced hood. He don't work much any more. I guess Sal Mineo got most of his roles. Yeah, I used that. I kept coming back to that movie image." (Wry & Danish To Go, MelodyMaker magazine, by Brian Case. Copenhagen. May 5, 1979).

- The motion picture "They Live By Night" (w. Farley Granger) was released October, 1949. "A powerful tale of the tribulations of a young couple running from the law. This film marked the directorial debut of Nicholas Ray. Based on the novel by "Thieves Like Us" by Edward Anderson. AKA: "The Twisted Road" and "Your Red Wagon." (� 1981-1999 Videolog. All rights reserved.) Further reading: Classic Film and Television, E-online, They Shoot Pictures, Marino Guida

The original film poster for the movie: "They Live By Night"