|

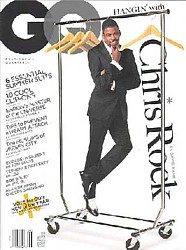

Title: Play It Like Your Hair's On Fire Source: GQ magazine (USA) June, 2002 by Elizabeth Gilbert. Transcription by Dorene LaLonde as sent to Tom Waits Yahoo discussionlist May 24, 2002. Photography by Mark Seliger Date: Washoe House/ Santa Rosa, CA. Published: June, 2002 Keywords: Alice/ Blood Money, Kathleen, recording Magazine front cover: June, 2002. Thanks to Dorene LaLonde for donating magazine |

Play It Like Your Hair's On Fire

Tom Waits Would Be America's Springsteen - If America Were A Strange Dispossessed Land Of Circus Freaks.

by Elizabeth Gilbert

He Never Looked Quite Right As A Child. He was small, thin, pale. He stood funny. He had a trick knee, psoriasis, postnasal drip. There was no comb, lotion or prayer in this world that would get his hair to lie down flat. He read too many books. He was unduly fascinated by carnivals, buried treasure and mariachi music. When he grew nervous, he rocked back and forth like a rabbi deep in prayer. He was often nervous. Moreover, there was something kind of wrong with him (maybe, he thinks now, some minor brush with autism) that made him almost painfully obsessed with sound. He heard noises the way van Gogh saw colors - exaggerated, beautiful, shimmering, scary. There were sounds all around him that made his hair stand on end, sounds nobody else seemed to hear. Cars driving by under his bedroom window roared louder than trains. If he waved his arm near his head, he heard a sharp whistle in his ear like the whipping of a fishing line. If he ran his hand across his bedsheets, he heard a harsh scrape, rougher than sandpaper. Engulfed by these noises, he'd be compelled to clear his head by reciting rhythmic nonsense syllables aloud (shack-a-bone, shack-a-bone, shack-a-bone, shack-a-bone...) until he could think straight again. When he was 11 years old, his father- a Spanish teacher who used to drive his boy out of San Diego and over the Mexican border for haircuts- left the family. So now the child didn't have a dad around anymore. He became fixated on dads as a result. He would visit the houses of his friends and neighbors, not to hang out with his buddies but to hang out with his buddies' dads. While the other kids were outside playing kickball in the sun, he would slip into the darkened den and sit there with somebody's father for the entire afternoon, listening to Sinatra records and talking about home insurance. He'd pretend to be a much older man(2), maybe even a father himself. Kicked back in some grown man's Barcalounger, this skinny little kid would clear his throat, lean forward and say, "So. How long you been with Aetna, Bob?" He wanted to be old so bad it drove him nuts. He couldn't wait to shave. At 11, he wore his grandfather's hat and cane. And he loved the music that old men loved. Music with some grizzled hair on its chest. Music whose day was long over. Dead music. Dad music. How 'bout that brass section, Bob?" he'd say to somebody's father while listening to the hi-fi on a quiet afternoon. "Can't find players like that anymore, can you, Bob?" This was back when he was in, like, sixth grade. So, yes, in case you were wondering- Tom Waits was always different.

I'm Waiting For Tom Waits on the porch of the Washoe House- one of California's oldest inns. It's in the middle of the grassy countryside of Sonoma County, across the street from a vineyard, next to a dairy farm and somewhat near the mysterious, secret rural location where Tom Waits lives. It was his decision to meet here. No mystery why he likes this place. The sloping wooden floors, the sticky-keyed piano in the bar, the yellowing dollar bills thumbtacked to the ceiling, the weary waitresses who look like they've been on the business end of some real hard love their whole lives- every story in the house is a true one. So I'm waiting for Tom Waits when a homeless man wanders up to me. Thin as a knife, weathered skin, clean and faded clothes. Eyes so pale he might be blind. He's dragging behind him a wagon, decorated with balloons and feathers and signs announcing that the world is coming to an end. This man is, I learn, walking all the way to Roswell, New Mexico. For the apocalypse. Which will be happening later this spring. I ask his name. He tells me that he was christened Roger but that God calls him by another name. ("For years I hear God talkin' to me, but he kept calling me Peter, so I thought he had the wrong guy. Then I realized Peter must be my real name. So now I listen.") With no special alarm, Roger-Peter informs me that this whole planet will be destroyed within a few short months. Pandemonium unleashed. Madness and death everywhere. Everybody burned to cinders. He points to the passing cars and says calmly, "These people like their comfortable lives now. But they won't like it one bit when the animals get loose." Appropriately enough, this is the exact moment when Tom Waits shows up. He wanders over to the porch. Thin as a knife, weathered skin, clean and faded clothes. "Tom Waits," I say, "meet Roger-Peter.' They shake hands. They look alike. You wouldn't know at first, necessarily, which one was the eccentric musical genius and which one was the derelict wandering doomsayer. There are some differences, of course. Roger-Peter has crazier eyes. But Tom Waits has a crazier voice. Waits, immediately comfortable with Roger-Peter, says, "You know, I saw you around here just the other night, walking down the middle of the highway." "God redirects traffic around me so I don't get hit," replies Roger-Peter. "I don't doubt that. I like your wagon. Tell me about all these signs you wrote. What are they all about?" "I'm finished talking now," Roger-Peter says, not impolitely but firmly. He stands up, gives us a bible as a parting gift, takes hold of his wagon and heads east to meet the total destruction of the universe. Waits watches him go, and as we head inside, he tells that he recently saw another hobo with apocalyptic signs walking down the same road. "He offered to sell me a donkey. A pregnant donkey. I had to go home and ask everyone if we could invest in a pregnant donkey. But they decided, no, that would be too much trouble."

For The Past Thirty Years, Tom Waits has had a musical career in this country unlike anybody else's. His was not a meteoric rise to fame. He just appeared- a rough, tender, melancholic, thoroughly experimental, lounge-singing, piano-playing, reclusive hobo in a $7 suit and an old man's hat- and that is what he has remained. Although he tinkers endlessly with his music (since his first album, 1973's Closing Time, he has given us tragic blues, narcotic jazz, sinister German opera and delirious, drunken carnival mambos, to name just a few styles), he has never once tinkered with his image, and that's how you know it isn't an "image." You don't see much of Tom Waits in public, although he's not a total hermit. He does go on tour every now and again, he has performed on The Tonight Show(3), and he shows up in the occasional movie (The Cotton Club, Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula, Robert Altman's Short Cuts) as a brilliant, scene-stealing character actor. Still, he prefers his privacy. He agreed to meet me today only because he has a new album coming out and he guesses he should probably promote it. Actually, he has two albums. (One is called Alice, the other is called Blood Money(4), and their single complexity and dark beauty shall be discussed at a later point in this article, so please hold tight.) Tom Waits is, famously, not the easiest interview out there. Reporters often get frustrated with him because he speaks inaudibly or "won't give straight answers." (When asked once why he had allowed six long years to pass between albums, Waits replied stonily, "I was stuck in traffic.") He's notorious for telling make-believe stories about himself. Not out of malice, mind you. Mostly just to pass the time. He quite enjoys the lies that have been printed about him over the years. ("My father was a knife-thrower," he has said. "And my mother was a trapeze artist. So we were a show-business family.") He's not the most marketable guy out there, either. He doesn't have the conventional good looks or a very nice voice. He has been called "gravelly voiced" so many times over the decades, you'd think journalists were required by law to describe him this way. Tom Waits has grown a bit weary of this description. He prefers other metaphors. A little midwestern girl once wrote him a letter saying that his voice reminded her a cherry bomb and a clown, to which he replied, "You got it, babe. Thanks for listening." As a songwriter, he has an unerring instinct for melancholy and melody. His wife says that all his songs can be divided into two major categories- Grim Reapers and Grand Weepers. The latter will knock you to the very floor with sadness. (A devastating little number called "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis" comes to mind.) He has never had a hit, though Rod Stewart did take Waits's "Downtown Train" to the top of the charts. But other Tom Waits songs aren't so radio-friendly. (How 'bout this for a catchy pop lyric: Uncle Bill will never leave a will/And the tumor's as big as an egg/He has a mistress, she's Puerto Rican/And I heard she has a wooden leg.) It's this darkness and eccentricity that have kept him from being a megastar. Still, he has never vanished into obscurity. For thirty years, as bigger and more conventional rock stars have shimmered and melted away in hot spotlights all around him, Tom Waits has stayed on his dimly lit side stage, sitting at his piano (or guitar or sousaphone or cowbell or fifty-gallon oil drum) creating extraordinary sounds for a loyal audience. As for the devotion he inspires and how he claimed his unique position in American music, the artist has only this to say: "There's an aspect of going into show business that's like joining the circus. You come to learn that there's certain people in show business who do the equivalent of biting the heads off chickens. But, then, of course, there's the aerialists...and sideshow curiosities. You work with what you came with. Well, maybe I came in with no legs. But I can walk on my hands and play the guitar. So that's just me using my imagination to work with the system."

Tom Waits Is Full Of Facts. He leans in close to me and says, "The male spider. After he strings four strands of his web, he steps off to the side, lifts one leg and strums them. The chord that this makes? This attracts the female spider. I'm curious about that chord...." Waits keeps these facts jotted down in a small notebook, which is also filled with driving directions and unfinished songs and hangman games he has been playing with his young son. His handwriting is a crazy wobbling of huge, scrawly capital letters. You'd swear it was the penmanship of a crippled man who has been forced to hold his pencil in his mouth. He thumbs through his notebook like he's thumbing through his own scattered memory. This provided me excellent opportunity to stare at his face. He looks good for a man of 50-however-many-years-old-he-is. He's been clean and sober for almost a decade, and it shows. Doesn't even smoke anymore. No puffiness along the jaw. Clear eyes. Four deep parallel lines are grooved into his forehead, as evenly spaced as if they'd been dug there with a kitchen fork. He's far better looking (handsome, even) in real life than he is on stage and screen, where -lost in the struggle of performance- he often employs such puzzled facial contortions and shambling postures and spastically waving arms that he looks (and I'm sorry to say this about my hero) something like an oversize organ-grinder's monkey. But here, in this dark old restaurant, he's nothing but dignified. He even looks like he's in shape. Which leads me to try to picture Tom Waits jogging on a treadmill. At a gym. Wearing what? "Ah, here's another interesting fact," he says. "Heinz 57." He picks up the bottle of Heinz 57 from the table to illustrate his story. Between 1938 and 1945," he says, "Heinz released a soup only in Germany. It was an alphabet soup. But in addition to every letter of the alphabet, they included swastikas in every can." "You're kidding me." He puts the bottle down. "I imagine it would be called pastika." It's a great story. Too bad further investigation proves it to be an urban myth. Not that it matters. What matters that it gets Tom Waits to thinking. Gets him to thinking about a lot of things. Pigs, for instance. He's concerned because scientists are splicing human genes into pigs these days. Apparently, this is to ensure that the animal's internal organs are more accessible for transplant into human bodies. Ethically, Waits thinks this is a horrific notion. It's also having an unsettling effect on the appearance of the pigs. "I saw pictures of these pigs," he muses. "You look at 'em and you say, 'Geez! That's Uncle Frank! Looks just like him!"

Which Brings Us To His Wife. Chances are, it was Tom Waits's wife who showed him the photograph of the experimental pig-humans, because she reads four local newspapers a day and cuts out all the weird stories. You can also bet she's the person who dug up the story about the swastika-noodle soup. And if there's anyone who has ever heard the mating chord of the male spider, it's probably Kathleen Brennan. But who is Kathleen Brennan? Hard to know, exactly. She's the most mysterious figure in the whole Tom Waits mythology. Newspaper articles and press releases always describe her the same way, as "the wife and longtime collaborator of the gravely voiced singer." You will see her name on all of his albums after 1985. ("All songs written by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan.") She's everywhere, but invisible. She's private as a banker, rare as a unicorn, never talks to reporters. But she is the very center of Tom Waits - his muse, his partner and mother of his three children. And sometimes, when he is playing live, you will hear him mumble, almost to himself, "This one's for Kathleen," before he eases into a slow and tender rendition of "Jersey Girl." I've never met the woman, and I know nothing for certain about her, except what her husband has told me. Which means that she is a person thoroughly composed, in my mind, of Tom Waits's words. Which means she's the closest thing out there to a living Tom Waits song. He has called her "an incandescent presence" in his life and music. She's "a rhododendron, an orchid and an oak." He has described her as a cross between Eurdora Welty and Joan Jett." She has "the four B's. Beauty, brightness, bravery, and brains." He insists that's she's the truly creative force in the relationship, the feral influence who challenges his "pragmatic" limitations and stirs intrigue into all their music. ("She has dreams like Hieronymus Bosch(5) .... She'll start talking in tongues and I'll take it all down.") He says "she speaks to my subtext, not my context." He claims she has expanded his vision so enormously as an artist that he can hardly bear to listen to any of the music he wrote before they met. "She rescued me," he says. "I'd be playing in a steak house right now if it wasn't for her. I wouldn't even be playing in a steak house. I'd be cooking in a steak house." "She's the egret in the family," he says. "I'm the mule.'

"We Met On New Year's Eve." Tom Waits tells me. He loves talking about his wife. You can see it, the pleasure it gives him. He tries not to go too nuts with it, of course, because he does want to protect her privacy. (Which is why he sometimes dodges interviewers' questions about his wife with typical Waitsian nonsense stories. Yeah, he'll say, She's a bush pilot. Or a soda jerk. Runs a big motel down in Miami. Or this: He once claimed he fell for Kathleen because she was the first woman he'd ever met who could "stick a knitting needle through her lip and still drink coffee.") And yet he wants to talk about here because- you can just see it- he loves the way her name feels in his mouth. They met in Hollywood, back in the early 1980s. Waits was writing the music for the Coppola movie One from the Heart, and Kathleen Brennan was a script supervisor on the film. Their courtship had all the drunken, spinning, time-warping delirium of a good New Year's Eve party in someone else's house. When they were first falling in love, they used to drive wildly around L.A. at all hours and she'd purposely try to get him lost, just for the entertainment value. She'd tell him to take a left, then hop on the freeway, then cross over Adams Boulevard, then straight through the ghetto, then into a worse ghetto, then another left... "We'd end up in Indian country," Waits remembers. "Out where nobody could even believe we were there. Places where you could get shot just for wearing corduroy. We were going into these bars- I don't know what was protecting us- but we were loaded. God protects drunks and fools and little children. And dogs. Jesus, we had so much fun." They got married at the Always Forever Yours Wedding Chapel (6) on Manchester Boulevard in Watts. ("It was planned at midnight for a 1 A.M. wedding." says Waits. "We made things happen around here!") They'd known each other, what? Two months? Maybe Three? They had to page the guy who married them. A pastor carried a beeper. The Right Reverend Donald W. Washington. "She thought it was a bad omen that it was a $70 wedding and she had fifty bucks and I only had twenty. She said, "This is a hell of a way to start a relationship.' I was like, "C'mon baby, I'll make it up to you, I'll get you later....'" There wasn't much of a honeymoon: Soon after the wedding, the couple realized they were dead broke. Waits was already a celebrated musician, but he'd made some serious young-artist mistakes with contracts and money(7) , and now it was looking like maybe he was dried-up. Plus, he was on the splits with his manager. And legal headaches? Everywhere. And studio producers trying to put corny string sections behind his darkest songs? And who owned him, exactly? And how had this happened? It was at this point that his new bride stepped in and encouraged her husband to blow off the whole industry. Screw it, Kathleen suggested. You don't need these outside people, anyhow. You can produce your own work. Manage your own career. Arrange your own songs. Forget about security. Who needs security when you have freedom? The two of them would get by somehow, no matter what. It's like she was always saying: "Whatever you bring home, baby, I'll cook it up. You bring home a possum and a coon? We will live off it." The result of her dare was Swordfishtrombones - a big, brassy, bluesy, gospel-grooved, dark-textured, critically adored declaration of artistic independence. An album like none before it. A boldly drawn line, running right through the center of Tom Waits's work, dividing his life into two neat categories: Before Kathleen Brennan and after Kathleen Brennan. "Yeah," Waits says, and he's still all dazzled about her. "She's really radical."

They Live In The Countryside. In an old house. They have neighbors, like the guy who collects roadkill to shellac and make into art. And then there are the Seventh-Day Adventists and the Jehovah's Witnesses who knock on the door wanting to talk about Jesus. Waits always lets them in and offers them coffee and listens politely to their preaching because he thinks they are such sweet, lonely people. He only recently realized that they must think the same of him. Waits drives a 1960 four-door Cadillac Coup DeVille. It's a bigger car than he probably needs, and he admits that. It devours gas, smells terrible, radio doesn't work. But it's good for little day trips, like visits to the dump. Dumps, salvage yards, rummage sales, junk shops- these are his special retreats. Waits loves to find strange and resonant objects hidden deep in piles of garbage, objects he can rescue and turn into new kinds of musical instruments. "I like to imagine how it feels for the object to become music," he says. "Imagine you're the lid to a fifty-gallon drum. That's your job. You work at that. That's your whole life. Then one day I find you and I say, "We're gonna drill a hole in you, run a wire through you, hang you from the ceiling of the studio, bang on you with a mallet, and now you're in show business, baby!" Sometimes, though, he just goes searching for doors. He loves doors. They're his biggest indulgence. He's always coming home with more doors- Victorian, barn, French... His wife will protest, "But we already have a door!" and Waits will say, "But this one comes with such nice windows, baby!" The Waits household has a family dog, too. Waits feels a special affinity for the animal and believes the two of them have a lot in common: Like "nerves", he says. "Barking at things that are inaudible. A need to mark a territory. I'm kinda like that. If I've been gone for three days, come home, first thing I have to do is take a walk around the house and establish myself again. I walk all over, touch everything, kick things, sit on things. Remind the room and everyone else that I'm back." He's home almost all the time, because- unlike other dads- he doesn't have a day job. Which is why he's known by the local schools as the guy they can count on whenever they need an adult to do the driving for a field trip. "I'm down with the field trips," Waits says. "I got the big car. I'm always looking for a nine-passenger opportunity." Recently, he took a group of kids to a guitar factory. It was a small operation, run by music types. "So I'm waiting for somebody to recognize me. OK, I think, someone's gonna come up and say, "You're that guy, right?" Now, I've been there for, like, two hours. Nothing. Nothing. Now I'm getting pissed. In fact, I'm starting to pose over by the display case. Still waiting, but nothing all day. I get back in the car. I'm a little despondent. I mean, it's my field. I expect a nod or a wink, but nothing." Waits takes a pause to stir his coffee. "So a week later, we go on another field trip. It's a recycling thing. OK, I'm in. We pull up to the dump and six guys surround my car- 'Hey! It's Tom Waits!'" He shrugs wearily, like he's telling the timeworn story of his life. "Everybody knows me at the dump."

Perhaps The Most Singular feature about Tom Waits as an artist- the thing that makes him the anti-Picasso- is the way he has braided his creative life into his home life with such wit and grace. This whole idea runs contrary to our every stereotype about how geniuses need to work- about their explosive interpersonal relationships, about the lives (particularly the women's lives) they must consume in order to feed their inspiration, about all the painful destruction they leave in the wake of invention. But this is not Tom Waits. A collaborator at heart, he has never had to make the difficult choice between creativity and procreativity. At the Waits house, it's all thrown in there together- spilling out of the kitchen, which is also the office, which is also where the dog is disciplined, where the kids are raised, where the songs are written and where the coffee is poured for the wandering preachers. All of it somehow influences the rest. The kids were certainly never a deterrent to the creativity- just further inspiration for it. He remembers the time his daughter helped him write a song. "We were on a bus coming to L.A. And it was really cold outside. There was this transgender person, to be politically correct, standing on a corner wearing a short little top with a lot of midriff showing, a lot of heavy eye makeup and dyed hair and a really short skirt. And this guy, or girl, was dancing all by himself. And my little girl saw it and said, "It must be really hard to dance like that when you're so cold and there's no music.'" Waits took his daughter's exquisite observation and worked into a ballad called "Hold On"- a song of unspeakably aching hopefulness that was nominated for a Grammy and became the cornerstone of his album Mule Variations. "Children make up the best songs, anyway," he says. "Better than grown-ups. Kids are always working on songs and throwing them away, like little origami things or paper airplanes. They don't care if they lose it; they'll just make another one." This openness is what every artist needs. Be ready to receive the inspiration when it comes; be ready to let it go when it vanishes. He believes that if a song "really wants to be written down, it'll stick in my head. If it wasn't interesting enough for me to remember it, well, it can just move along and go get in someone else's song." "Some songs," he has learned, "don't want to be recorded." You can't wrestle with them or you'll only scare them off more. Trying to capture them sometimes "is trying to trap birds." Fortunately, he says, other songs come easy, like "digging potatoes out of the ground." Others are sticky and weird, like "gum found under an old table." Clumsy and uncooperative songs may only be useful "to cut up as bait and use 'em to catch other songs." Of course, the best songs of all are those that enter you "like dreams taken through a straw.' In those moments, all you can be, Waits says, is grateful. Like a clever kid with a new toy, Waits is always willing to play with a new song, to see what else it can become. He'll play with it forever in and out of the studio, in ways a real grown-up would never imagine. He'll pick it apart, turn it inside out, drag it backward through the mud, ride a bicycle over it- anything he can imagine to make it sound thicker, rougher, deeper, different. "I like my music," he says, "with the pulp and skin and seeds." He's always fighting for new ways to hear or perform things. ("Play it like your hair's on fire,"(8) he has instructed musicians in the studio, when he can't explain his vision any other way. "Play it like a midget's Bar Mitzvah.") He wants to see the very guts of sound. Just as the architect Frank Gehry believes buildings are more beautiful when they're under construction than when they are completed, Tom Waits likes to see the naked skeleton of song. This is why he finds one of the most exciting sounds in all of music to be that of a symphony orchestra warming up. "There's something about that moment, when they have no idea what they sound like...," he rhapsodizes. "Someone's tightening up the threads of the timpani, someone else is playing snatches of an old song he hasn't played in a long time, someone else is going over that phrasing she keeps tripping on. It's like a documentary photograph- everyone is doing something without knowing they're being watched. And the audience is talking and paying no attention because it isn't music yet, right? But for me, there's lots of times when the lights go down and the show starts and I'm disappointed. Because nothing can live up to what I've just heard." He abhors patterns, familiarity and ruts. He stopped playing the piano for a while because, as he says, his hands had become like old dogs, always returning to the same place. Instead, he had fantasies of pushing his piano down the stairs and recording that noise. He is known to sing through a police megaphone. He once recorded a song in which the primary instrument was a creaking door. And on Blood Money, one of his new albums, he actually recorded a solo on a calliope- a huge, howling, ungodly pneumatic organ, best known for providing music for merry-go-rounds. "I tell you," Waits says, "playing a calliope is an experience. There's an old expression, 'Never let your daughter marry a calliope player.' Because they're all out of their minds. Because the calliope is so flaming loud. Louder than a bagpipe. In the old days, they used them to announce the arrival of the circus because you could literally hear it three miles away. Imagine something you could hear three miles away, and now you're right in front of it, in a studio...playing it like a piano, and your face is red, you're hair is sticking up, you're sweating. You could scream and nobody could hear you. It's probably the most visceral music experience I've ever had. And when you're done, you feel like you should probably should go to the doctor. Just check me over, Doc, I did a couple of numbers on the calliope and I want you to take me through the paces." He likes a day in the studio to end, he says, "when my knees are all skinned up and my pants are wet and my hair's off to one side and I feel like I've been in the foxhole all day. I don't think comfort is good for music. It's good to come out with skinned knuckles after wrestling with something you can't see. I like it when you come home at the end of the day from recording and someone says, "What happened to your hand?" And you don't even know. When you're in that place, you can dance on a broken ankle." That's a good day of work. A bad day is when the right sound won't reveal itself. Then Waits will pace in tight circles, rock back and forth, rub his hand over his neck, tug out his hair. He and Kathleen have a code for this troublesome moment. They say to each other, "Doctor, our flamingo is sick." Because how do you heal a sick flamingo? Why are its feathers falling out? Why are its eyes runny? Why is it so depressed? Who the hell knows? It's a fucking flamingo- a weird pink foreign bird. And music is just that weird, just that foreign. It is at difficult moments like these that Kathleen will show up with novel ideas. (What if we played it like we were in China? But with banjos?) She'll bring him a Balinese folk dance to listen to, or old recordings from the Smithsonian of Negro field hollers. Or she'll just take the flamingo off his hands for a while, take it for a walk, try to put some food into it. I ask Tom Waits who does the bulk of the songwriting around the house- he or his wife? He says there's no way to judge it. It's like anything else in a good marriage. Sometimes it's fifty-fifty; sometimes it's ninety-ten; sometimes one person does all the work; sometimes the other. Gamely, he reaches for metaphors: "I wash, she dries." "I hold the nail, she swings the hammer." "I'm the prospector, she's the cook." "I bring home the flamingo, she beheads it." In the end, he concludes this way: "It's like two people borrowing the same ten bucks back and forth for years. After a while, you don't even write it down anymore. Just put it on the tab. Forget it."

Now, About Those two new albums. They are called Alice and Blood Money. They are recordings of songs Waits has written in recent years for the stage, in collaboration with the visionary theatre director Robert Wilson. Alice is a dreamy, haunting cycle of love songs based on real-life story of a middle-aged Victorian minister who fell in love with an enchanting 9-year-old girl. The little girl's name was Alice. The minister's name was Reverend Charles Dodgson, but he is more widely known by his pen name (Lewis Carroll) and for the surreal, not totally-made-for-children children's story (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland) he wrote as a valentine to the girl he adored. On Alice, Waits uses his voice as if he were singing tormented lullabies to somebody who's dying, or leaving forever, or growing up too fast. The second album, Blood Money, is completely different. It's based on the German playwright Georg Buchner's unfinished masterwork, Woyzeck, about a jealous soldier who murders his lover in a park. (Waits considered calling the album Woyzeck, but then he figured, Jesus Christ, who would buy an album with a name like Woyzeck?) This album is all rich, complex, mysterious, dark tomes about the concussion of hatred against love. The sound is not quite industrial or grating, but there is a discord to these songs, almost a physical discomfort. These are dirty little dirges, with gritty titles like "Misery Is The River Of The World" and "Everything Goes To Hell." The good people at Waits's label, Anti, struck a bit of genius when they decided to release these two albums simultaneously. Because the contrasts of Alice and Blood Money perfectly highlight the two aspects of Waits's musical character that have been colliding in his work for decades. On one hand, the man has an unmatched instinct for melody. Nobody can write a more heartbreaking ballad than Waits. On the other hand, he has shown a lifelong desire to unbuckle those pretty melodies, cleave them into parts like a butcher, rearrange the parts like into some grotesque new beast and then leave it in the sun to rot. It's almost as if he's afraid that if he stuck to writing lovely ballads, he might become Billy Joel. Yet he loves music too much to write purely brainy experimental music like John Cage, either. So he does both, going back and forth, sometimes on the same album, sometimes in the same song, sometimes in the same phrase. (In the past, he's explained this schizophrenia as some musical version of the alcoholic cycle- first you're nice; then you punch a hole through the wall; then you sober up and apologize by giving flowers to everyone; then you crash your car into the swimming pool...) This tempestuous struggle with music is the story of his life. Because while Tom Waits and sound have always been infatuated with each other, their relationship has never been a simple one. On the contrary, it's the kind of relationship that leaves broken china in its wake. There was a time, back when Waits was a child, when he had not yet made any kind of peace with sound and he was veritably tormented by the drunken disorderliness of it all. He remembers that the noises of this world felt like insects to him- insects that burrowed through every wall, crawled under every crack, penetrated every room, making absolute silence an absolute impossibility. With hypersensitivity like that (added to his inherently dark nature), Tom Waits could so easily have gone mad. Instead, he embarked on a mission to arrange a truce between himself and sound. A truce that, over the years, has become something like a collaboration and- with these two new albums- finally feels like a real marriage. Because here, on Alice and Blood Money, you can see it all together, side-by-side. All that Tom Waits is capable of. All the beauty and all the perversity. All the talent and all the discord. All that he wants to honor and all that he wants to dismantle. All of it gorgeous, all of it transporting. So gorgeously transporting, in fact, that when you listen to these songs, you will feel as if somebody has blindfolded you, hypnotized you, given you opium, taken away your bearings and now is leading you backward on a carousel of your own past lives, asking you to touch all the dusty wooden animals of your old fears and lost loves, asking you to recognize them with only your hands. Or maybe that's just how it felt for me.

At The End Of It All, the dining room in this old inn has emptied and filled and filled again several times around us. We've been sitting here talking for hours. The light has changed and changed again. But now Waits stretches and says, gosh, he feels like he knows me so well that he's almost tempted to take me on a visit to the local dump. "It's not far from here," he says. The dump! With Tom Waits! My mind thrills at the thought- the two of us banging on sheet metal or blowing songs into old blue milk-of-magnesia bottles. Sweet Jesus, I suddenly feel like there is nothing I have ever wanted more then to go to the dump with Tom Waits. But then he notices the time and shakes his head. A trip to the dump is impossible today, it turns out. He was due home hours ago. His wife is probably wondering where he is. And, anyhow, if I'm going to catch that flight out of San Francisco, shouldn't I get moving? "I still have fifteen minutes before I have to leave!" I say, not yet letting go of the dream. "Maybe we could run over to the dump real quick!" He gives me a grave look. My heart sinks. I already know the answer. "Fifteen minutes would not be fair to the dump," Tom Waits pronounces, proving that he is above all things a fair and respectful man. "Fifteen minutes would be an insult to the dump."

Elizabeth Gilbert is a GQ writer-at-large. Her book The Last American Man, based on a piece she wrote for GQ about the rugged outdoorsman Eustance Conway, has just been published by Viking.

Notes:

(2) He'd pretend to be a much older man: Gilbert has an interesting point here. This posture is indeed an integral part of Waits' early stage persona. We don't know how Waits behaved when he was still in high school, but it does indeed look as if he started behaving like an older person from the time on he worked at Napoleone Pizza House (ca. 1965 - 1968)

(3) He has performed on The Tonight Show: Tonight Show with Jay Leno (2000) TW: musical performer and interviewee. NBC television talkshow with Jay Leno. NBC Studios. Burbank/ USA (broadcast March 15, 2000). Interview and performs "House Where Nobody Lives"

(4) One is called Alice, the other is called Blood Money: Alice (the play) premiered on December 19, 1992 at the Thalia Theater, Hamburg/ Germany. Further reading: Alice. Woyzeck (the play) premiered November 18, 2000 at the Betty Nansen Theatre in Copenhagen/ Denmark. Further reading: Woyzeck

(5) She has dreams like Hieronymus Bosch: Dutch renaissance painter. Further reading: WebMuseum, Artcyclopedia, Artchive, Dutch domain

(6) They got married at the Always Forever Yours Wedding Chapel: Further reading: Always Forever Yours Wedding Chapel

(7) He'd made some serious young-artist mistakes with contracts and money: refering to conflicts with Waits's former manager Herb Cohen. Further reading: Copyright

(8) Play it like your hair's on fire: As first mentioned in "Mojo Interview With Tom Waits" Mojo magazine (USA) April, 1999 by Barney Hoskyns (Tom Waits: "When you say you want musicians to play like their hair is one fire, you want someone who understands what that means. Sometimes that requires a very particular person that you have a shorthand with over time.")