|

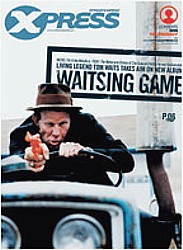

Title: Nighthawk In The Light Of Day Magazine front cover: Ottawa Xpress Magazine. October 7, 2004 |

Nighthawk In The Light Of Day

Melora Koepke

Tom Waits gets Real Gone on new album and forgets the piano at home

"Hi, I'm calling from Tom Waits' office," says the pleasant publicist voice on the other end of the line. "I'll put Tom through now. Are you ready?"

Tom Waits has an office? It strikes me as weird to be on the phone business-style, waiting to talk with a man who has written so many deeply moving love songs involving telephones. "Hello, hello, there is this Martha/ this is old Tom Frost," I think to myself, quoting from the love ballad from Closing Time (1973). "I am calling long distance/ don't worry 'bout the cost." Then there's "I got a telephone call from Istanbul, my baby's coming home today" from Frank's Wild Years (1987). There's Please Call Me, Baby from The Early Years Vol. II, and so on.

Telephones are in the Tom Waits idiom like whiskey, rain, red shoes, automobiles, bars, barns, coffee shops, Illinois, tango, female hitchhikers, the movies, glass eyes and peg legs, Jesus, shotguns and the circus. Good things every last one, and ample fodder for Waits' 24-odd albums, movie soundtracks, musical plays, road shows and collaborations, which have influenced the American songbook like no other. His songs have been covered by Springsteen, The Eagles, Johnny Cash and, yes, Rod Stewart, to name a few. He's gotta do business. So a telephone, sure. But an office?

"Hello there, where you calling from?" a voice on the other end of the line interrupts my reverie. Tom Waits sounds conversational, relaxed and slightly bored, but it's Tom Waits nevertheless. For some reason, I kind of expected him to be growling or hollering through a bullhorn.

To introduce myself, I apologize in advance for any clever-sounding questions I may be about to ask. Most of the interviews I've ever read with Waits are always trying to find something to say that hasn't been said by way of being remarkable to him. This is ridiculous, since the point of Waits is mostly that nobody says anything better than he himself does, so in an interview you're tempted to ask him nothing and everything all at once.

"Well, let's make a deal then," says Waits congenially. "If you won't try to be clever, then I won't either.

"My deal is, usually they know too much about you, or they don't know nothing about you. The nothin' is usually fine with me... I like to be invisible. I like to work on my songs on my album, and that's how I use a microphone. But sometimes [talking to people] is good for business. So here we are."

Harlots for haylofts

It's still hard to imagine Waits sitting in a room somewhere, rattling on like a kid in church, waiting for someone in an L.A. office to patch him through. This is a man whose fans are zealous and scholar-like and obsessive in a way that no other living American singer/songwriter can boast (except maybe Bob Dylan, and rumour has it that Waits himself is one of those Dylan fans).

Waits' rapturous following is fuelled, at least in recent years, entirely by his records - he's not much of a touring persona these days. In the 1970s he was on the road almost constantly, through the bar years of yearning lyrics and jazzy melodies: Closing Time, The Heart of Saturday Night, Nighthawks at the Diner, Blue Valentine, and Heartattack and Vine etc. In 1982, though, something happened: Waits was working on a soundtrack for the Francis Ford Coppola movie One From the Heart(1) (for which he was Oscar-nominated with Crystal Gayle) when he met a script girl named Kathleen Brennan. Then he (or rather they, as Kathleen is credited as a producer and co-writer on almost everything since 1982) really started to shake things up: Swordfishtrombones was born the next year (and also marked his switch from Asylum to Island Records, and the beginning of his insistence on retaining artistic control of production with Brennan). Then came Rain Dogs, Frank's Wild Years, the play Big Time, and then Bone Machine, The Black Rider (his first play with Robert Wilson), Mule Variations, Alice (the second Robert Wilson collaboration) and Blood Money. All this after he got married and moved to the country and had kids. The barn years following the bar years, and it was beautiful. At least that's the way one likes to imagine it.

But back to the conversation: It's always nice to ask reluctant conversationalists about their families, and I've always been curious about Waits' uncommon collaboration with his wife.

"You wanna know exactly how it happens? I dunno if I can tell you about that," he says. "She's the heavy equipment operator, the tree surgeon, the palm reader. She's the ventriloquist and I'm the dummy. I also think she's got the heart of an old newspaperman and she's a bathing beauty. It's a great combination."

I ask how life in a rural environment has changed the worldview of a Tom Waits record. Since Rain Dogs at least, there is less crooning about neon and yellow broken lines on the highway, and more storytelling about axes, orchard murders and little girls who disappear into the woods. Is this an indication of newly pastoral sensibilities? And what, exactly, is his thing with barns?

"I don't know... barns? They're all over the place. I really don't know. I never had anybody ask that before," says Waits. "Sure, if you move, you see different things outside your window... you know, it's amazing. You go back to L.A. and there are so many words on your windshield, hundreds of 'em, everywhere."

"When I moved out to the sticks, I felt like an unplugged appliance. It gets really dark and really, really quiet. Now the quiet is part of the music, and so are the trucks going by. I let those sounds into the recordings... I like to feel like the world is collaborating with me."

Pockets full of words

"Words are already music all by themselves, see?" says Waits, by way of describing his song craft. "Folk expressions and names of towns, names of people - that's musical to me. I hear them at family gatherings, or from books. Some are made up... sometimes they just come to you. You could make up a name right now [singing]: 'Norberry Ellen and Coriander Pyle, had 16 children in the usual style.'(2) It's a trick. A place you gotta get to. It's more like daydreams... and you're doing incantations and talking in tongues.

"You're under a spell, it's like you're high, and things start stickin' to you, and you collect them, and at the end of the day you empty your pockets out on the floor."

Someone once observed to me that every emotion it was possible for a human being to have in a lifetime was available in Tom Waits' songs, and usually in the songs of one record. No album illustrates Waits' approach to songwriting as an emotional road trip better than the forthcoming Real Gone.

"My theory is that all songs have to have weather in them, and the names of towns and streets, and something to eat, usually," says Waits. "People in songs, you can't just stick 'em in there and not give 'em something to eat! You are creating a world, and you are asking people to enter that world - you gotta give 'em something to do once they get there."

Waits, so far, is only playing three shows in the New World to support Real Gone (two in Vancouver and one in Seattle), but claims these are only a trial run of an extended tour that will, presumably, include more shows further afield. The last time he set foot in La Belle Province was the legendary 1987 Big Time show at Th��tre Outremont.(3)

Real Gone is a cacophony of African and Latin rhythms, reggae and call-and-response axe-swinging blues ballads. It's also the first album Waits has ever made without a piano.

"My deal is, if you don't bring it with you, you're definitely gonna need it. I brought it, so I didn't use it. Piano is indoors, and this is an outdoor record. Sometimes when I use piano, it brings me indoors when I don't want to come in yet."

Contributors to this big country sound include long-standing Waits collaborators Marc Ribot (on guitar), Brian "Brain" Mantia (on drums), Primus' Les Claypool and Waits' son Casey (on turntables)(4).

As usual, the track list encompasses the full range of human experience, but more than anything, and for the first time, a prevalent theme on Real Gone is the insecurity in Waits' homeland. Not only is there a song about "plundering mercenaries" called Hoist That Rag, but Sins of My Father brilliantly turns the present regime into a terrifying carnival sideshow: "Smack dab in the middle of a dirty lie/ the star-spangled glitter of his one good eye/ everybody knows the game was rigged/ justice wears suspenders and a powdered wig."

Yet as much as these songs are about this war, and this president, Waits' songwriting approach remains universally specific, and vice versa.

"Well, that's the trick isn't it?" asks Waits. "Not to make things too personal. It's the art of it. If you're going to write about something that's current, then when it's no longer current, the song will have no value. How do you photograph your driveway and make it seem like the road of life? Why would people buy pictures of people they don't know? You have to shape it, make it recognizable. If you're going to write a song about the war, you better make it about war itself, not just about some story in the newspaper. Well, that's just my way. It's not the way."

Real Gone is in stores now

Notes:

(1) One From The Heart: further reading: One From The Heart

(2) Norberry Ellen and Coriander Pyle: quoting freely from "Eyeball Kid" (Mule Variations, 1999): "Well, Zenora Bariella and Coriander Pyle They had sixteen children in the usual style."

(3) Big Time show at Th��tre Outremont: October 11, 1987. Outremount Theatre. Montreal/ Canada. Early show and late show

(4) Waits' son Casey (on turntables): Casey Xavier Waits played on the 4-track album 'Hold On' (1999). Drums and co-writer ("Big Face Money"). The album 'Real Gone' (2004). Turntables (Top Of The Hill, Metropolitan Glide), Percussion (Hoist That Rag, Don't Go Into That Barn), Claps (Shake It), Drums (Dead And Lovely, Make It Rain). Production crew. Casey also stepped in a couple of times for Andrew Borger (drums) during the Mule Variations Tour (Congresgebouw, The Hague/ The Netherlands. June 21, 1999)