|

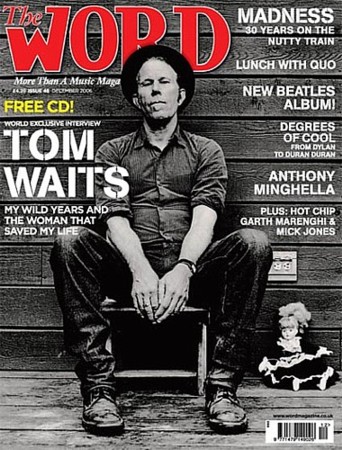

Title: My Wild Years And The Woman That Saved My Life Source: Word magazine (UK), December 2006. By Mick Brown. Thanks to Jarlath Golding for donating transcript and scans. Date: Published November 9, 2006 Key words: Orphans, politics, television, childhood, parents divorce, Johnny Cash, Bukowski, songwriting, Kathleen, Sinatra Magazine front cover: Word magazine (UK), December 2006. Published: November 9, 2006. Photography by Anton Corbijn. |

My Wild Years And The Woman That Saved My Life

"I'm alive because of her. I was a mess. I was addicted. I wouldn't have made it. I really was saved at the last minute, like deus ex machina. I'm like The Roadrunner, you know, who ran off the cliff and looked around, and just before he dropped like a bullet, he ran back on the smoke from his feet, back to the cliff. That's me. I've been fortunate enough to be able to walk on smoke."

Mick Brown meets Tom Waits - the man who had his luck extended.

"My career," Tom Waits once said(1)," is more like a dog. Sometimes it comes when you call. Sometimes it gets up in your lap. Sometimes it rolls over. Sometimes it just won't do anything. In recent years it has been walking on its hind legs, doing cartwheels and even singing in tune."

A strange dog, indeed.

Waits was born in Pomona, California in 1949, the son of a Spanish teacher. A recalcitrant student, he dropped out of high school at the age of 15, continuing his education as "a jack-off of all trades", including washer-up and short-order cook at a pizza parlour, and nightclub doorman(2). "Place must have been really hurting if they had me as their bouncer. Everybody got in..."

His career can be neatly divided into two distinct parts. Between 1974 and 1979 he made a series of albums about that area of town marked out by the pawnbroker, the tattoo parlour and the flophouse hotel - wonderful stories in which raindrops were diamonds, every hooker was an angel, and skid-row bums were "little boys"(3). 'With his boho threads and graveyard pallor, Waits didn't just sing the life of the inebriated bar-fly, down in the gutter but looking up at the skies - he appeared to be living it, to the point where it became hard to tell if he was an actor playing a part, or whether the part was playing the actor. Either way, what was clear was that Waits, who was drinking heavily and living badly, was at risk of being annihilated by his creation.

In 1980 he married Kathleen Brennan, a script-editor whom he had met while working on the soundtrack for Francis Ford Coppola's film One From The Heart. A radical overhaul ensued. Waits fired his manager Herb Cohen, and severed relations with his producer Bones Howe. He left his record company, Asylum, and signed with Island. His first record under the new arrangement, Swordfishtrombones, was also the first Waits had produced himself, and marked a radical shift in direction. The songs became more abstract - wheezing polkas, funeral marches and drunken sea-shanties; suites written for rattling bones and chains; country blues re-written as a Tod Browning script. He enjoyed an extra-curricular career as a film actor and collaborated on stage productions with the avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson. He stopped drinking, and all but gave up touring, preferring to spend the time with his growing family. The abiding curiosity about all this was that Waits' radical swerve towards the avant-garde, the idiosyncratic and the wilfully obscure has made him more successful, in commercial terms, than at any time in his career. His album Mule Variations, released in 1999, brought him his first UK Top 10 entry in 25 years, and his highest ever position (#20) in the US.

This month sees the release of a new three-album set called Orphans. It is the Waits aficionado's dream, every facet of his extraordinary canon rolled into one package: the plangent sentimentalist; the avant-gardist; the shamanistic bone-shaker and channeller; the bar-room storyteller. One album, subtitled Bawlers, consists of lovelorn ballads, piano blues and Irish airs. Brawlers stirs together rockabilly, Beefheartian yodels and roughneck blues and roll. Bastards is a collection of off-kilter instrumentals, tall tales, yarns and poems, including tributes to two of Waits' great literary influences and idols, Jack Kerouac and Charles Bukowski, and the bleakest childrens story(4) you've ever heard ("Once upon a time there was a poor child with no father and no mother, and everything was dead. No one was left in the entire world.."). Waits says his own children, "can do it word for word. They get all choked up..."

The origins of Orphans are complicated. A handful of the songs have already appeared elsewhere in various projects. King Kong is Waits' cover of a Daniel Johnston song, which was previously released on a tribute album, The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered, in 2004. What Keeps Mankind Alive first appeared on an anthology of the songs of Brecht and Weill in 1990; a scarifying version of Heigh Ho, on a Hal Willner produced compilation of Walt Disney songs originally released in 1988. Little Drop Of Poison has already been heard on the soundtrack for Wim Wenders' film The End Of Violence (and contains a vintage piece of Waits' word-play - "I'm all alone, I've smoked my friends down to the filter').

Of the remainder, some are recordings from the sessions for Mule Variations and Real Gone which were not included on those albums, some songs from that period that have been recorded anew; some are completely new songs. As Waits puts it: "Kathleen and I wanted the record to be like emptying our pockets on the table after an evening of gambling, burglary; and cow-tipping." The treasures here are too numerous to count, but a few stand out. Down There By The Train is Waits' roof-raising, gospelised version of one of his own compositions that was first recorded by Johnny Cash on American Recordings in 1994. Road To Peace, the most explicitly political song Waits has ever recorded, is an epic dissertation on the Israeli-Palestine conflict, which moves from the story of a young suicide bomber to a pitiless anatomy of the futility of war, invoking Henry Kissinger's infamous observation that "we have.no friends, America only has interests", and concluding that "Maybe God himself needs/ All of our help/ And is lost upon the road to peace". Meanwhile, Bend Down The Branches and The World Keeps Turning are Waits at his most unrepentantly romantic and heartfelt. But as much as this collection is a demonstration of Waits' extraordinary range as a composer and musician, it is also testament to his singular talents as a singer. Nobody sounds like Tom Waits - but here, nobody sounds like Tom Waits in quite as many different ways and guises. "At the centre of this record is my voice," Waits says. "I try my best to chug, stomp, weep, whisper, moan, wheeze, scat, blurt, rage, whine, and seduce. 'With my voice, I can sound like a girl, the boogieman, a Theremin, a cherry bomb, a clown, a doctor, a murderer. I can be tribal. ironic or disturbed. My voice is really my instrument."

Waits lives with his wife and three children in a large, rambling, wood-framed house in Sonoma County, Northern California. 'Wine country (an irony: he gave up drinking 14 years ago). Large and rambling - or so I've been told. Waits guards his privacy fiercely, and never entertains journalists at home. His preferred meeting-place on this occasion is the Little Amsterdam(5), a run-down roadhouse, a few miles from the town of Petaluma, on a quiet back road which appears to be seldom bothered by traffic. The restaurant is faced with foreclosure (only optimists need apply) dark, nicotine-stained and, at lunch-time, completely devoid of custom. Waits is well-known here. One wall is devoted to framed photographs and news-clippings about him.

Waits' affection for old cars - delapidated Caddies, pick-up trucks - is well-known too, and it occasions a mild frisson of surprise to see him turn into the parking-lot in a new, top-of-the-range 4WD Lexus, carrying a bulging black attach� case under his arm. He is dressed in a black suit. He looks fit and healthy. He has spoken in the past of how he spent most of his childhood wishing he were an old man - an ambition in which he was to prove remarkably successful. In his thirties, he looked like a man in his sixties. Now he seems to be reversing the process, and at the age of 56 he looks 10 years younger. Only his familiar rough, tubercular growl suggests a punishing and misspent youth.

He is an arresting talker; conversation follows a rambling, circuitous path, replete with digressions and parenthetical thoughts, ruminative pauses, jokes and tall stories. Occasionally, to illustrate a point - or simply for the sheer hell of it - he bursts into song, rocking back on his chair, his hands reaching out, as if for an invisible piano.

From his case he pulls a few scraps of paper - notes and aide-memoires for the conversation, written in a spidery hand. Digging deeper, he produces a flattened and rusted tin-can. "Here, this is for you. I found it on the way here." Noting my expression of bemusement (and gratitude, of course), he goes on. "Those are hard to find, because nowadays it's all aluminum. That's a real tin can. I don't think you'll get through the airport with that. Put it in your baggage. You still might get in trouble..."

WORD: It's very noticeable watching television here how America is being kept in a state of constant anxiety over 'the war on terror'. But here you are in a very quiet and beautiful part of the country - do you feel insulated from all of that?

TW: Well first of all, I don't have a TV. That helps. I pick up the newspaper. 'Course you can't really get around it. They run us with fear. We're all dominated by it, but there's nothing new about that. It's just this is the current form of fear. In the '50s it was Communism, so this is just a new '-ism'. And there'll be another '-ism' after this, I guess. I try to stay current with things. I have a lot of friends who keep me current. But I threw the television in the swimming pool about a year ago, and I haven't been able to get a picture on it. I'm still trying.

WORD: You got rid of it because you were sick and tired of it, or you didn't want your children exposed to it?

TW: That was more it. When they were kids there was the danger of flipping around the dial, you know. Especially giving them the changer and then leaving the room. You come back and you don't know what they'll be watching. And the strange thing about it, with the ability to flip channels so quickly it makes you wish that you could change the channels on other things when you're bored. Like your mother talking to you, or your teacher. Or even reading a book: "I want a picture now. I'm sick of these words." I think also what happens is that kids, without knowing it, are editing a very peculiar film for themselves. Because that's what editors do in films. They say, you know what? I'm bored. We need a new image. So when you sit down and do this for an hour and a half you've created a film - dental surgery to the Middle East conflict, to new-born baby, to a diaper commercial, to a swimming pool filled with dead bodies. You've edited your own film based on your inability to hold attention

WORD: And constructed a very distorted view of the world...

TW: Distorted or not. Maybe that's the only vision to have of it. I don't know. Because I don't even know if there's a real vision of the world. As soon as it reaches your eyes, your imagination takes hold. If you tell somebody seven words that have no relationship to each other the mind will go to work - refrigerator, heart-beat, dog-crap, diving-board, Dutch masters and broken watch. Okay, I get it... we're all spies and now we've been given this puzzle. The mind never sleeps. Not 'til you're dead. And sometimes it works harder while you're asleep than while you're awake.

WORD: Do you ever find yourself thinking too much?

TW: I don't know if I think too much. My wife would say I don't think enough. But she's not here, so I'll say, yes I think much too much and I need a break. I'm like everybody. My life is like an air-traffic controller. Moments of boredom broken up by moments of sheer terror. Some days I'm floating down the creek on a lily-pad, then the next moment the wind is tearing my skin off. And you just deal with it.

WORD: Do you like being the age you are? Does life become better, more interesting to you, as you get older?

TW: Do you mean I can go back to when I was 19 ?

WORD: I can't offer you that deal, I'm afraid. But is 56 a good age to be?

TW: It's really the only age to be when you think about it. I'm on the home stretch. None of us can go back, but you go back in your mind your imagination. Nobody lives in a linear fashion. Some days I'm about nine; other days I'm about 90. We're all trying to move forward and backward. I think what happens is your past goes from being like a little film, to a photograph and from there it gets more like abstract painting - the further I get from my past, the more it gets like an out-of-focus image or a Rauschenberg. I remember when I was a kid, being in a car with my folks, and we go on a long drive to visit my grandmother over maybe 100 railroad tracks. We were always waiting for trains to pass. And the magic of that for a kid, hearing the bell - ding, ding and counting the cars as they go by. And then the other thing - I knew we were getting further out of town when I could smell horses. When I got that smell, then I was glued to the window, looking for my first horse. As soon as that smell hit, it was like perfume to me - it was like the smell of watermelon, or coffee, or popcorn. That was like a promise of all these great things. This was in Southern California. La Verne, Pomona. Let's see ... Snoop Dogg lives out there now. Crazy. It was like a lot of orange groves and just the one road, Foothill Boulevard. It wasn't this grid, like the back of a radio, that it is now. It was much simpler then. I was eight or nine. That was a long time to go without a cigarette, stuck in the car with my family. I couldn't wait to get to my grandparents' so I could smoke. I was smoking two packs a day by the time I was 11.

WORD: Do you miss it?

TW: Smoking? I don't. I laid that off and I laid off drinking. My wife said, You drank enough.

WORD: Wives are often better at knowing what's good for you than you know yourself.

TW: WelI, it comes from love, you know? 'I want you to stick around, goddamit!' I saw a guy at crap table in Las Vegas with his wife. I'd been playing craps next to him for an hour, and his face getting redder and redder, getting angrier and angrier. And finally he grabbed his chest and he went down on the carpet. His eyes rolled back. And his wife was pounding on his chest in the middle of the casino, screaming, "You can't die on me now, Ray!" She said that over and over again. And then I heard, "New shooter coming out, get him out of here." This is Las Vegas. And then there's a little ripple through the crowd, while they bring the stretcher, and Ray's gone. It closed up like the ocean.

WORD: Your parents separated when you were 11 What effect did that have on you?

TW: Huge. But I didn't understand why at the time. It was an extreme loss of power, and totally unpredictable, as you can imagine. I was in turmoil over it for a long time. I stayed with my mother and two sisters. But when I think back on it, my dad was an alcoholic then. He realy left - this is getting a little personal - to sit in a dark bar and drink whatever, Glenlivet. He was a binge drinker. So there was no real cognisance of his drinking problem from my point of view. So he kind of removed himself- he was the bad tooth in the smile, and he kind of pulled himself out. So in a sense I come from a family of runners. And if I had followed in my father's footsteps I'd be a runner myself, and so would my kids.

WORD: So do you think that has a hereditary aspect that you've had to be alert to?

TW: Well, like anything, the genetic pull to following your father's footsteps, whether he teaches at Harvard or died on the Bowery... there's a path that he left for you. And you get to a crossroads eventually and you see his path, and there's a magnetic quality to it, so yeah I was pulled. But he was a great story-teller, so in a way what I've done was a way of honouring him.

WORD: There have always been a lot of religious allusions in your records, both musical and lyrical, of a salvation army band, revival tent variety On this record you've got a traditional gospel song, Lord I've Been Changed, and a gospel song you've written yourself, Down There By The Train. Is it the music you love or the sentiment?

TW: I don't know.. I always thought religion should be more visceral and that you should get beat up a little by it, you know? I was hitchhiking through Arizona(6), it was New Year's Eve and I got stuck in a little town called Stanfield, Arizona. You think Arizona's hot - in January it's 10 below zero - and I'm not getting any rides. I'm about 17. And an old woman named Mrs Anderson comes out to the sidewalk and I'm with my good buddy Sam, and she says, "It's getting a little cold, it's getting a little dark, it's New Year's Eve, come in the church". And they sat us down in the back of the church, and it was all Pentecostal. They had a band up there; two Mexican guys and a black drummer and an old guy on the guitar - very weird - and a boy about seven playing piano. And they did this talking in tongues. I had never experienced anything like this before, so as far as I was concerned it was like scat singing; they were just going crazy. We were in the back, starting to laugh because it was unusual, and we were young and naive. And at the end of the service they took up an offering and they gave all of the money to us. They said, "We want to honour our wayfaring strangers, our travellers in the back who've come a long way to be with us tonight". They gave us a basket of money, and we bought a motel that night, warm with a TV, trucks out the back. And we got up next morning, and we hit a ride and went all the way to California. That was probably the most pivotal religious experience I've had. If I was going to join a church, I'd join that church.

WORD: Down There By The Train(7) pursues that theme of redemption. What's the history of that song?

TW: How many years ago, I don't know, Johnny Cash did a version of it, when he was doing the first of those American Recordings with Rick Rubin. I don't know who asked me; somebody said, "You got any songs for Johnny Cash?" I just about fell off my chair. I had a song and I hadn't recorded it. So I said, "Hey - it's got all the stuff that Johnny likes - trains and death, John Wilkes Booth, the cross... OK!"

WORD: It's such a wonderful song, the idea that even the worst sinners will be saved. "Charlie Whitman is holding on to Dillinger's wings, they're both down there by the train..."

TW: Yeah, yeah, available to all. Charles Whitman -- he's the one that went up a tower in Texas and shot all those people. He was probably bipolar. [He reaches in his bag and pulls out a promotional copy of the new album, the sleeve printed with strange and unusual facts.] We got the famous last words of dying men here, all that sort of stuff. Oscar Wilde - "Either that wallpaper goes or I do". Isn't that beautiful? That at that final moment he could still be witty. He'd leave you with his wit. I dug that. WC Fields: "On the whole I'd rather be in Philadelphia". You know, he was so paranoid because he grew up poor that he put money in hundreds of banks all over America. Every time he was on the road he'd put money in a bank, and he'd make up a name for the account. And when he died he was penniless. But he had millions of dollars, apparently, all spread out, and he'd forgotten the names. They're probably still there. What else we got here... Queen Elizabeth was annoyed by her red nose. Her attendants were accustomed to powder it every few minutes to keep it presentable. Wow! That's something else. That's not a bad job to have. We all should have somebody to do that.

WORD: What made you decide to structure the new record in this way, as three quite discrete albums?

TW: It was hard to sequence because the tempos were different, the subjects were so different. At first, to be honest with you, when we tried to sequence it in a normal fashion - like an up-tempo song, then a ballad, paced like you traditionally try to do, but it didn't make any sense. You didn't know why we went from this terrible thing to this light thing. It needed a faucet and a sink. It just didn't work. So Kathleen said, "Oh yeah - slow ones, rockers, spoken. In a general way. If you're a ballad, you go over there. Door Number Three." And it worked.

WORD: You didn't sit down one day a couple of years back and say, 'OK, I'm going to write 45 new songs to go with these odds and ends'?

TW: No, no. They happened over time and then they were put in a drawer. Some were recorded, and then we didn't do anything with it. Or we made a record and the song didn't fit on the record. Or it was a song that fell behind the stove while we were making dinner, can't use it. Well, let's cannibalise it, cut it up and use it for bait. No! It's a good song! Okay, fuck it, let's just put it over here. And then I lose them. Then it's in a drawer with microphones and hair oil - "I knew it would be ruined if you didn't use it." Then I end up buying some of the songs from a guy in Russia, for big money [laughs]. This is a guy who's somehow got hold of these tapes. A plumber! In Russia! I'm talking to him on the phone in the middle of the night, negotating a price for my own shit!

WORD: You're kidding me.

TW: No! I'm not kidding. Poor Little Lamb ...there's probably 12, 13 things on there that this Russian guy had.

WORD: How did he come to have them?

TW: I don't know! That's the weird thing. It's the internet now, you know? I had no DATs on these, I had no multi-tracks. I don't have a vault. He had recordings of these songs, good recordings. These were recordings that had come off the desk at one session or another, and then I didn't get the DAT of. I did the project, and then these got lost and there was only one copy and someone got hold of it and made two copies and he sold them to somebody and... who knows? When you don't keep track of things meticulously, which I try to but I'm not good at, and now I've got people collecting weird stuff of mine.

WORD: So some of these are old songs that you've recorded a new, having bought them from a man in Russia?

TW: Right. Songs that might have been on Mule Variations, or out-takes from Real Gone. And then after we did Real Gone we just carried on and wrote a whole bunch of new songs. You say, you'd better keep going. We'd better get a holding tank. And then they say, "Hey the project's over". But it doesn't really end until someone takes it from you and says, "We need this - we have to master it". So a lot of those we just kept writing. And then the cover versions are just affectionate tributes - the Kerouac, and the Bukowski.

WORD: You do two versions of the same Jack Kerouac piece, one entitled Home I'll Never Be and the other, On The Road(8).

TW: Yeah, one is a ballad and one is a blues. What happened, I made the song first with Primus, the rocker version, Home I'll Never Be. And then Hal Wiliner asked me to come down and play for an Allen Ginsberg memorial. There were a lot of people there talking about him. I didn't have a band. So I said, well, this is an actual song written by Jack Kerouac - an a capella song they found on one of the tapes. [Sings] "I left New York, 1949. To go across the country without a damn blame dime! Montana in the cold, cold fall! found my father in a gambling hall..." Kerouac sang it alone on a microphone - it's on a collection of his work - and it's beautiful, very touching. So I tried to do my version like that. I ended up liking it. Somebody had the tape from that night, so we stuck it on there.

WORD: It seems very much like an act of homage for you. And to precede that with the Charles Bukowski poem, Nirvana, about a young man on the road, stopping in a cafe and being struck dumb with a sense of wonder -"The curious feeling swam through him/ That everything was beautiful there/ That it would always stay beautiful there..." What I love about that Bukowski poem is that it's completely unapologetic in its sense of wonder, completely innocent and open-hearted.

TW: Yeah, and we've all been on that bus, where you wish you could just freeze everything right now. Like people say, "Shoot me! Things are good. Shoot me right now!" [laughs] The moment in the church in Arizona was like that for me. 'Course, in that community you wouldn't want to say. "Shoot me". Because they would.

WORD: There's that wonderful entry in Jack Kerouac's letters where he describes a similar scene, that he later dramatised in On The Road, where he's in a diner in Wyoming having breakfast, and a cowboy walks in -- the first cowboy Kerouac's seen - and he describes it as if the very essence of life itself was gusting in the door. You seem to be very alive to those kind of moments, those epiphanies, in your songs.

TW: Well, I think once you've experienced some of those moments you try to influence them. You're always waiting for them to happen, the way cats wait for things to move around the house; you sit quietly and wait, you know. You never know when they're going to happen, and you want to be ready. I think that's what people look for in songs. I write down song titles usually, and usually something that you're going through emotionally will make a particular title leap out at you. This is what my wife says - there's something that you're already working on inside that this song will be the manifestation of. Now you have a container. The first thing that anybody ever created was a container. Someone made a bowl to hold the water. And then they made a song about the bowl that held the water. You know, people only travel really with their seeds and with their songs. In Bosnia they interviewed a lot of the refugees - they'd left with nothing and they asked them what they had, and they had seeds, in their pockets, from their gardens. And their songs. That was it. Once you're nourished in that most fundamental way, everything else will follow.

WORD: So do you feel writing songs, making music, is an honourable calling?

TW: Gee, I don't know. There are times when it seems very... triffing and trivial. Making these little songs up, I feel like I'm glueing macaroni onto a piece of cardboard and painting it gold. And then other times...when Johnny Cash wants to sing one of your songs, you think, "Oh man..." Because there's a hierarchy in music, and there's certain indications that you're doing better, you're getting closer to the source.

WORD: Who's at the top of that hierarchy for you?

TW: Gee.., well, there's a lot of people. That's a big room. I'd say, the Gershwins and Bob Dylan and Louis Armstrong and Ray Charles. Howlin' Wolf, people like that. Giants among men. Judy Garland and Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday...

WORD: It's invidious to ask, but I'll ask it anyway - do you have any sense of your own position in that hierarchy?

TW: I don't know. It would be presumptuous of me to say. It's better to have some things like that said about you rather than say it yourself. [Looking momentarily discomfited, Waits rifles through his notes] But I was going to say, I've just found some things here I wanted to mention... the thing about songs is that they're about so many things. Crop failure. My son died. Cautionary tales. There's a song about everything. And when you think about how songs were written and how they were kept alive before the recording industry, that to me is fascinating. 'Cause we were all part of writing those songs when it says 'Traditional' or 'Negro spiritual' or 'Public Domain'. Like all the songs that Alan Lomax collected. Those were songs that were written by all of us. Those were songs that if you learned it, you would change a verse or line. Just like a recipe. When you got a recipe from your neighbour, or if somebody asked for a recipe, the traditional thing to do was to change one thing about it. You never gave anybody your recipe. No, it's only a cup and a half of flour, honey instead of sugar, chopped quince instead of apples. And that's how songs moved along. You would add your verse. Or, it doesn't apply in this town, in this weather, with that gender. I have to change it to make it fit.

WORD: And now things are recorded, enshrined, like a monument.

TW: Right. But it also keeps it from decomposing in the ground. Like being buried in a coffin.

WORD: You said a song very often begins with a phrase or a title that becomes a container. Can you give me an example of that?

TW: Oh, alright. [Consults notes] Here's some titles that aren't songs yet. I'm In Love With The Girl On The Mudflaps - like the big semi trucks. I'm In Love With The Girl On The Raisin Box. Things Will Be Different In Chicago. You can almost hear the song. [Sings in a robust, bier-keller baritone] "Things will be different in Chicago..." So I pick 'em according to cadence and rhythm and the value of the sentence. They All Died Singing - that's a title. I love all these circus freaks - you know, Turtle Boy, Mule-Face Woman, Camel Girl. There was an act in the early 1900s, they were Siamese twins - two women and they both sang - and they billed themselves as The Two Headed Nightingale. One was a soprano, one was a contralto. They used to break people's hearts. There's a song right there.

WORD: You like places in songs, don't you? Minneapolis. Kentucky Avenue. On this album you've got Elkhart, Indiana in The First Kiss.

TW: My theory is that if you're going to make a song it's like packing somebody a lunch. You've got to give me weather, a name of a town, you've got to give me something to do and something to eat. It helps with the atmosphere. If you want to invite somebody into a song of yours it's kind of like inviting them into your home, and you have to give them some place to sit down. Because there's too many songs that are already written that are well-furnished. 'With a new song you've got to use some old tricks.'

WORD: A lot of the Bawlers are co-written with Kathleen - more of the Bawlers than the Brawlers. Who's the more sentimental of the two of you? Is she bringing out your sentimentality, or are you bringing out hers?

TW: A little of both. The chemistry between two people you can never really go back in and pick out what bits are you and what bits are me. It's a melting pot. We've melted. But she will say to me things like, "If you write another song where you take somebody's finger off, I'm going to leave you. If you lop somebody's arm off, or if you make another guy blind in a song, I'm going to leave you."

WORD: So she's the humanitarian in the partnership?

TW: Well she's from the Midwest. Like the song A Little Rain, which is on Bone Machine. [Sings in a bleary manner] "Well, the ice-man's mule is parked outside the bar/ Where a man with missing fingers plays a strange guitar/ And the German dwarf dances with the butcher's son/ And a little rain never hurt no one..." She says, 'Why do you have to take his fingers off? Why can't you just let him play the guitar like a normal guy in a bar? God! And why does the German guy have to be dwarf? And if he is, why do we have to know? It's not a film!" "But honey, sometimes you gotta shorten people, lop off a limb. It's just artistic licence."

WORD: lf there's a picture hanging straight on the wall, you like to tilt it to one side.

TW: Yeah, yeah, I do. I get pleasure like that.

WORD: And Kathleen comes along and straightens it.

TW: Sometimes. It's an ongoing battle. Wait for the bell and come out fighting. The only trouble is when the gloves come off. We're always arm-wrestling over various things, and when you get into lines in a song, a line that you love... (breaks into his voice, then his wife] "You know what? The weakest part about this song is that third line, scratch it... "'Are you kidding me? I'm going to move it up front. It's the most important line in the song!" Somebody told me if you're stuck in a song and you can't move, take out the best lines. Get rid of them. Now finish it. That's good advice.

WORD: I get the sense that marriage to Kathleen changed you enormously.

TW: Oh God, yeah, no question about it. In a good way. I'm alive because of her(9). I was a mess. I was addicted. I wouldn't have made it. I really was saved at the last minute, like deus ex machina. I'm like The Roadrunner, you know, who ran off the cliff and looked around, and just before he dropped like a bullet, he ran back on the smoke from his feet, back to the cliff. That's me. I've been fortunate enough to be able to walk on smoke. I got sober about 14 years ago; it was a big turning point. And then having kids, you know... once you've had kids you can't imagine not having kids. So my wife and kids really did save my life.

WORD: It's a paradox, isn't it? Cyril Connolly said, "There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hail". But for you it seems to have been the opposite - the pram in the hail, domestic life, was the catalyst for a radical transformation inyour music.

TW: You know, Nikola Tesla [the inventor of alternating current] said the reason he was celibate was... he said, "Name me one important invention that was created by a man who was married". 'Course he was also compulsive. He had to wash his hands 100 times. He had a thing about threes - everything had to be divisible by three, the number of steps to the door, the number of times he'd go around the house before he entered the door - three, three, three, three. He worked with Edison and then quit. He's really the reason we got electricity. But Edison got the medicine. And Tesla got the receipt.

WORD: But for you a stable, happy domestic life has been a boon to creativity not a detriment.

TW: I guess so. In the old days my home was on the road, and that eventually got very scary for me. I felt I was looking for my home out there. It's like looking for food, or looking for money round a Coke machine.

WORD: There's a lot of romantic idealism about that kind of life which experience proves to be just that... romantic idealism. Charles Bukowski's life seems to exemplify that.

TW: Well, none of us really know what Bukowski's life was like. We know what we have read, and what we've gathered from the work and what we've imagined. Essentially, there's backstage and there's on-stage, when you're a performer. You know what we allow you to know.

WORD: Did you meet Bukowski?

TW: A couple of times. It's like when I met Keith Richards, you try to match them drink for drink. But you're a novice, you're a child. You're drinking with a roaring pirate. Whatever you know about holding your liquor you'd better let go of it right now. So I thought I could hang in there but I wasn't able to hang in there, with either one of them. They're made out of different stock. They're like dockworkers. But it was interesting. I met Bukowski at his house. Barbet Schroeder was a friend of mine, and they tried to get me to be in that movie, Barfly, playing Bukowski. They offered a lot of money, but I just couldn't do it, plus I didn't consider myself a good enough actor to do something like that. But Bukowski... I guess everybody when you're young and you enter the arts you find father figures. For me it was more profound because I had no father - no operating father - so I found other men that supplied all that for me. I was looking for those guys all the time.

WORD: I understand after your father left home you'd go to your friends' homes and hang out with their fathers.

TW: [Laughs] That's true. I was in the den, listening to Bing Crosby while my friends were out shooting hoops. "Tom! What are you doing, man? Talking to my Dad?" I'd say, "Yeah, - what of it? You're not using him. I'm borrowing your father, for God's sake. You don't appreciate your father: He's been working for ETNA for 29 years..."

WORD: So that's where you got your taste for double-knits and Hoagy Carmichael.

TW: I probably did! It's kind of like you start imitating the things that are around you, whatever they are. I took note of Frank Sinatra. I liked the scar on the side of his face. He had this tremendous birthmark that he was always careful to obscure in photographs, but I saw one photo that showed this - it almost looked like a burn on the side of his face.

WORD: You've recorded a song indelibly associated with Sinatra, Young At Heart(10), on this new album. It's too corny to be true.

TW: [Drily] Yeah, that song always moved me. My wife just thinks it's hilarious because she says, "You sound so goddamned depressed singing it. When you say, And here's the best part/ You have a head start/ If you are among the very young at heart'.. .she says, 'I don't believe that bullshit for a minute." [Laughs] "Young at heart, my ass!"

Notes:

(1) "My career," Tom Waits once said: quoted from "Tom Waits Makes Good", Los Angeles Times: Robert Sabbag. February 22, 1987

(2) Short-order cook at a pizza parlour, and nightclub doorman: further reading: Napoleone Pizza House, The Heritage

(3) And skid-row bums were "little boys": quoting On The Nickel (Heartattack And Vine, 1980)."And what becomes of all the little boys, who never comb their hair They're lined up all around the block, on the Nickel over there."

(4) The bleakest childrens story: Children's Story of Bastards, 2006

(5) Little Amsterdam: Further reading: Little Amsterdam

(6) I was hitchhiking through Arizona: anecdote of hitchiking with Sam Jones, as told since ca. 1983:

- Tom Waits (1983): "I was stranded in Arizona on the route 66. It was freezing cold and I slept in a ditch. I pulled all these leaves all over on top of me and dug a hole and shoved my feet in this hole. It was about 20 below and no cars going by. Everything was closed. When I woke up in the morning there was a Pentecostal church right over the road. I walked over there with leaves in my hair and sand on the side of my face. This woman named Mrs. Anderson came. It was like New Years Eve... Yeah, it was New Year's Eve. She said: "We're having services here and you are welcome to join us." So I sat at the back pew in this tiny little church. And this mutant rock'n'roll band got up and started playing these old hymns in such a broken sort of way. They were preaching, and every time they said something about the devil or evil or going down the wrong path she gestured in the back of the church to me. And everyone would turn around and look and shake their heads and then turn back to the preacher. It gave me a complex that I grew up with." (Source: "Tom Waits - Swordfishtrombones". Island Promo interview. 1983)

- Tom Waits (1988): "I hitchhiked to Arizona with Sam Jones while I was still a high school student. And on New Year's Eve, when it was about 10 degrees out, we got pulled into a Pentecostal church by a woman named Mrs. Anderson. We heard a full service, with talking in tongues. And there was a little band in there - guitar, drums, and bass along with the choir." (Source: Tom's Wild Years Interview Magazine (USA), by Francis Thumm. October, 1988)

- Tom Waits (1999): "I have slept in a graveyard and I have rode the rails. When I was a kid, I used to hitchhike all the time from California to Arizona with a buddy named Sam Jones. We would just see how far we could go in three days, on a weekend, see if we could get back by Monday. I remember one night in a fog, we got lost On this side road and didn't know where we were exactly. And the fog came in and we were really lost then and it was very cold. We dug a big ditch in a dry riverbed and we both laid in there and pulled all this dirt and leaves over us Iike a blanket. We're shivering in this ditch all night, and we woke up in the morning and the fog had cleared and right across from us was a diner; we couldn't see it through the fog. We went in and had a great breakfast, still my high-water mark for a great breakfast. The phantom diner."(Source: "The Man Who Howled Wolf" Magnet magazine, by Jonathan Valania. Astro Motel/ Santa Rosa. June-July, 1999).

- Tom Waits (2002): "I had some good things that happened to me hitchhiking, because I did wind up on a New Year's Eve in front of a Pentecostal church and an old woman named Mrs. Anderson came out. We were stuck in a town, with like 7 people in this town and trying to get out you know? And my buddy and I were out there for hours and hours and hours getting colder and colder and it was getting darker and darker. Finally she came over and she says: "Come on in the church here. It's warm and there's music and you can sit in the back row." And then we did and eh. They were singing and you know they had a tambourine an electric guitar and a drummer. They were talking in tongues and then they kept gesturing to me and my friend Sam(10): "These are our wayfaring strangers here." So we felt kinda important. And they took op a collection, they gave us some money, bought us a hotel room and a meal. We got up the next morning, then we hit the first ride at 7 in the morning and then we were gone. It was really nice, I still remember all that and it gave me a good feeling about traveling." (Source: ""Fresh Air with Terry Gross, produced in Philadelphia by WHYY" radio show. May 21, 2002)

- In Waits' 1974 press release for The Heart Of Saturday Night a Sam Jones is listed as one of his favourite writers. Sam Jones is also name-checked in "I wish I was in New Orleans" (1976) "And Clayborn Avenue me and you Sam Jones and all." He's also mentioned on the booklet of the album Nighthawks At The Diner: "Special thanks to Sam (I'll pay you if I can and when I get it) Jones."

(7) Down There By The Train: Read lyrics: Down There By The Train

(8) Home I'll Never Be and the other, On The Road: Recorded with Primus, early 1979. Read lyrics: On The Road.

(9) I'm alive because of her: Further reading: Quotes on Kathleen

(10) Young At Heart: Made famous by Frank Sinatra as (opening) song from the movie "Young At Heart" (1954). Waits version on Bawlers, 2006. Read lyrics: Young At Heart