|

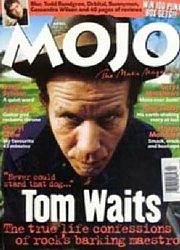

Title: Mojo Interview With Tom Waits Source: Mojo magazine (USA), by Barney Hoskyns. Transcription as published on http://www.rocksbackpages.com Date: Santa Rosa. April, 1999 Key Words: Mule Variations, Car accident, Charlie Musselwhite, Smokey Hormel, Bone Machine, Beck, Kathleen, Epitaph, Childhood, The Systems, National City, Randy Newman, Bones Howe, Frank Zappa, Troubadour, Bruce Springsteen, One From The Heart, Beautiful Maladies, William Burroughs, Manzanita Magazine front cover: Photography by Jill Furmanovsky |

| Accompanying picture |

Mojo Interview With Tom Waits

Tom Waits squats down on the fender of his blue Coupe de Ville and decides to tell a joke.

Two men, he says, are sitting on a bench in Central Park, talking about their

retirement.

"I got this new hobby," says one, "I took up beekeeping."

"That's nice," says the other.

"Yeah, I got 2,000 bees in my apartment."

"Two thousand, huh? Where you keep 'em?"

"Keep 'em in a shoebox."

"A shoebox? Isn't that a little uncomfortable?"

"Ah, fuck 'em"

According to Waits, Eddie Izzard(1) didn't get it either. Waits concedes that you probably have to have lived in New York City for a few years to fully appreciate the joke.

Watching him on this sun-dappled winter afternoon, kicking back on a country road on the outskirts of Santa Rosa, it's hard to imagine Waits living in New York City or any other city, come to that. With his feet planted in a pair of old boots and a nest of red-dyed hair dancing atop his creased, kindly face, he looks like he just wandered in from his backyard after a long afternoon of wrestling with some farm machinery. His strong, grarled fingers several adorned with chunky silver rings are grey-brown and calloused. When I ask him why he moved with his family to this part of northern California, he replies, succintly, that he likes to pee outside. One of the tracks on Waits' new, largely bucolic Mule Variations is a hilarious spoken-word piece called What's He Building in There?, and it could almost be about Waits himself. In it, a prying busybody tries to imagine what his eccentric neighbor is up to in his uninviting abode. As the monologue unfolds the conjecture becomes more and more fantastical:

"I swear to God I heard someone moaning low."

"There's poison underneath the sink, of course."

"I heard that he was up on the roof last night, signalling with a flashlight."

Sinister as the guy sounds, it's clear that Waits' sympathies lie with him rather than the speaker. Indeed, Waits laments the fact that America has become a country where any solitary activity appears to encourage suspicions that there's a serial killer, or a Unabomber, living next door. "We seem to be compelled to perceive our neighbors through the keyhole," he says, "There's always someone in the neighborhood the Boo Radley, the village idiot and you see that he drives this yellow station wagon without a windshield, and he has chickens in the backyard, and doesn't get home 'til 3 AM, and he says he's from Florida but the license says Indiana. so, you know, 'I don't trust him.' It's really a disturbed creative process."

Waits climbs into the 1970 Coupe de Ville a replacement, he informs me, for a 1967 model he totalled last year(2). ("I'm not hurt," he protested when his son Casey saw him staunching a head wound with a McDonald's takeout bag. Fortunately for Waits Sr, Casey begged to disagree.) He drives towards Santa Rosa, decrying the way people move up here from San Francisco, tear down the trees, then build gated communities called White Oaks or Pine Bluffs. He also talks about his midlife as an unlikely paterfamiliar.

Rickie Lee Jones, whom Waits squired when he lived in the '70s in the West Hollywood's notorious Tropicana Motel(3), was wont to remark that behind the man's sozzled, skid-row exterior was an old bear that wanted to settle down in a bungalow with a bunch of screaming kids. Give or take a couple of storeys, it turns out she was right. The last time I met Waits(4) , he was living in New York with his screenwriter wife Kathleen Brennan, and young daughter Kelly. Fourteen years on, he and Brennan have added Casey and a second son, Sullivan, to their brood.

"You know," he reflects as he drives, "I didn't wanna be the guy who woke up when he was 65 and said, 'Gee, I forgot to have kids.' I mean. Somebody took the time to have us, right?" Being a proper dad, as opposed to an absentee rock 'n' roll sperm bank, is clearly high on Waits' priority list. Even though he collaborates with Kathleen on most of his songs, there's precious little overlap between work and domesticity in their house. "Mostly my kids are just looking for any way I come in handy," he says, "Clothes, rides, money. that's all I'm good for. But I think it's the way it's supposed to be."

For the most part Waits is happy to answer questions about family life. But there's a wary guarded side to him that takes exception to prying. ("What's he building in there?") "Tom's a very contradictory character in that he's potentially violent if he thinks someone is fucking with him," Jim Jarmusch, who directed Waits in the wonderful Down by Law, has said, "But he's gentle and kind too. It sounds schizophrenic, but it makes perfect sense once you know him."

Jarmusch's observation calls to mind an evening in the early '80s when Waits rounded on a hapless Ian Hislop during a glib chat on the TV show Loose Talk. "Could you speak up a little?" Hislop innocently requested, unable to make out a word the gravel-toned Californian was saying. "I'll speak any damn way I please," was Waits' terse response to the future editor of Private Eye.

Waits will be 50 in December, which makes 1999 a good year to look back over his unique career. For the better part of three decades this weathered maverick has remained determinedly out-of-step with pop culture, or simply years ahead of it. When the British invaded America in the '60s, Waits played guitar in an R&B band called the Systems(5). When the world beat a path to Haight-Ashbury, he went back to the literature of the Beats and the jazz of the '40s and '50s. When the denim cowboys of southern California made pseudo-country rock records to snort cocaine by, Waits explored the Los Angeles of Raymond Chandler, penning sketches of melancholy lowlifes cruising diners on rainy nights. And when pop turned into a video parade of hideous hairstyles and bogus soul in the '80s, he offered up the primitive surrealism of Swordfishtrombones and Raindogs.

Two decades after The Heart of Saturday Night (1974) and Small Change (1976), America has finally caught up with Waits. Suddenly, one can't move for movies like Pulp Fiction, Get Shorty, LA Confidential, and the Big Lebowski, all bustling with characters straight out of Waits' songs. Where has Waits himself been? Apparently out of sight, though hardly idle: in a burst of energy in the first half of the decade, he scored Jarmusch's Night on Earth, collaborated with Robert Wilson and William Burroughs on a macarbe musical called the Black Rider, and recorded the stark, demented, Grammy-garnering Bone Machine. (Wearing his thespian hat, he also appeared as Lily Tomlin's mate in Robert Altman's Short Cuts, yet another LA movie populated by Waitsian misfits and sleazeballs.) Now, 30 years after he first left the San Diego suburb of National City to try his luck in Hollywood Babylon, Waits is releasing his first album in six years, a record that captures him in all his favoured moods and guises: barking bluesman (Big in Japan), maudlin balladeer (Take It with Me), Springsteenesque believer (Hold On), backwoods Dadaist (Eyeball Kid). He's still singing about dogs and moons and shoes and ditches and trees, and he still sounds like a mutant throwback: Howlin' Wolf by way of Harry Partch and Don Van Vliet, a poetic madman singing with the debauched growl of Orson Welles in a Touch of Evil.

Mule Variations, moreover, is coming out at a time when Waits' musical influence has never been greater when the Nick Caves and PJ Harveys of the world are carving careers out of the man's crazed Bible-belt imagery, and when everyone from Beck to Sparklehorse to Gomez is trafficking in his mangled country blues.

"With the digital revolution wound up and rattling, the deconstructionists are coming the wreckage of our age," Waits wrote in his introduction to Gravikords, Whirlies and Pyrophones(6), Bart Hopkins' 1996 book about experimental instruments. "They are cannibalising the marooned shuttle to send us on to a place that will sound like a roaring player piano left burning on the beach." Fitting words for these apocalyptic times.

*

The opening track on Mule Variations, Big in Japan, is a furious blues rocker in the vein of 16 Shells from a 30.6 and Goin' Out West. Isn't it a little ironic that here you are making music that's so much harder and grittier than you did when you were 23?

Yea, right, yeah. I always start at the wrong end of everything: throw out the instructions, and then wonder how you put this thing together. I don't know, maybe I'm raging against the dying light. What do they say? Youth is wasted on the young? You're more in touch maybe with those feelings the further you get from them. Time is not a line, or a road where you get further away from things, it's all exponential. Everything that you experienced when you are 18 is still with you. Something like 43 million tons of meteor dust fall from the heavens every day. and what that has to do with it I have no idea. And more importantly. on that same topic, while you're here you'll wanna check out the Banana Slug Festival.

I beg your pardon?

Gelatinous gastropods 10 inches long. People cook with them. You find them in your yard at about six in the morning. And this is the season of the banana slug.

Are they indigenous to northern California?

Yes. So indigenous, in fact, that a nephew of mine asked me to capture and send him one. And we did, and it was a big hit.

Do they have hallucinogenic properties?

Not that I know of, but they might. There's also a company round here that makes a wine out of ammonia, ox blood, and banana peels. There's no grapes involved. And the bottle is made out of bread and meat. I swear to God.

Is there any reason why you're playing so much less percussion on Mule Variations than you did on Bone Machine?

Gee, I don't know. You've stumped me there. Is that a true-or-false question? I don't know, when you're producing a record and you're also recording it yourself, a lot of people divide those jobs. You have to decide what your role is going to be. You farm out or subcontract the rest of the job. I don't always do my own electrical work at home, I usually hire an expert. So we hired professional musicians- and I don't know if I can honestly consider my part of that group. I am like the creator of forms and I sometimes get my own way. The main thing is to have people working with you that will succumb to the power of suggestion. The whole thing is kind of a hypnotic experience, and when you say you want musicians to play like their hair is one fire, you want someone who understands what that means. Sometimes that requires a very particular person that you have a shorthand with over time.

There are some terrific people on the album. The harmonica player Charlie Musselwhite, Beck's guitarist Smokey Hormel, along with the usual Waits suspects: Marc Ribot, Larry Taylor, Ralph Carney. How did Musselwhite come to play on the record?

Oh, we just did some gigs together, you know. I hadn't thought of using harmonica before. Somehow it suited the material, being more rural - what I like to call somewhere between surreal and rural, or surrural. Charlie is what I would consider a rather surrural gentleman. He has a tone like Ben Webster, and he developed that over a long period of time. He can play just one note and break your heart.

What about Hormel?

I used to see Smokey when he played with The Blasters in Los Angeles. They'd play this little Chinese restaurant, and I'd go see 'em there. And then Larry Taylor said, Let's get Smokey in here. So Smokey came up to the studio and brought in these West African instruments that he played on 'Low Side Of The Road'. They're these strange instruments made out of branches and gourds.

That track is amazing - it sounds like Beck's Hotwax crossed with Beefheart's Low Yo Yo Stuff, then slowed to 78 rpm. It's also the only track on Mule Variations which has anything to do with death, whereas Bone Machine seemed fixated with it.

When I was done with Bone Machine, we listened back and we were like, "Oh, man, everybody's got problems on this record." But the whole arc of it you don't really get a sense of it until it's all completely done. In the meantime, we were just doing the finer, closer work. You don't stand back from it and see how it all works together, then when it's all over you have to decide if it has four legs and a tail or what.

I know you are friendly with Beck. Are you a fan?

I like Beck very much. Saw him in concert a couple of times, and it really moved me. He's got real strong roots It's funny, I heard him talking about Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and I used to open shows for them in the old days(7). It was nice to hear a kid as young as he is talking about them, because I loved those guys. There's a really rich cultural heritage there, and it's nice to see that it's living on in someone as well-rounded and as good a spokesman as Beck seems to be. He's got some street credibility too, because from what I hear he was a busker and really went out there and stood on a corner and drew a crowd. I love that. Those are some real important chops to have. And when he goes up on-stage and throws that guitar around like a Hula-Hoop, it's pretty remarkable what he can do to an audience.

How do you and Kathleen collaborate on songs like Lowside of the Road?

Oh, y'know, one person holds the nail, the other swings the hammer. We collaborate on everything, really. She writes more from her dreams and I write more from the world. When you're making songs you're navigating in the dark, and you don't know what's correct. Given another five minutes you can ruin a song. So time's always a collaborator. Over the years she's exposed me to a lot of music. She doesn't like the limelight, but she's an incandescent presence on all songs we work on together.

Do you think musician's marriages last longer when both parties are involved in the music, at least in the career?

Well, we've got a little mom-and-pop business. I'm the prospector, she's the cook. I bring the flamingo, she beheads it; I drop it in the water, she takes off the feathers. no-one wants to eat it.

The word is that you're planning to tour this year. True or false?

A tour usually implies fifty cities. I'II play some major cities. As to whether I'm gonna be wearing a leotard or not, nothing is definitely planned. All these things have yet to be decided.

You're now on Epitaph, a label more commonly associated with punk bands like Rancid. Given what's happening in the music industry right now - with legendary labels being swallowed up left, right, and centre - it looks like you got off Island in the nick of time.

I guess. I signed with Epitaph on the basis of mutual enthusiasm. They're musicians that started the label, which appeals to me. Most record guys came from the garment industry, so this makes it a little easier to communicate. I don't mind them coming in the studio. The boss, Brett Gurewitz, is great. First thing you see when you walk in the Epitaph office is an enormous engine from some muscle car. They have good taste in cars, good taste in barbecue, and good taste in music. Wayne Kramer(8) told me everything on Epitaph was 160 beats a minute, so he was glad to have some company. My kids listen to some of the bands. See, I'm at the age now where if you wanna find out what's happening, you ask your kids: "Check this out, Dad."

D'you still listen to hip hop? A little DMX at cocktail hour, perhaps?

Oh, sure, yeah. What do my kids listen to? Tricky?

Funny you should say that - I've always felt Tricky must be one of your secret disciples.

I felt kinship there, 'cause he likes to go through the rabbit hole, where the bushes close behind you. And I just started playing around with samples, which is kind of a new world to me. Brought a guy in, DJ Mark "The III Media" Reitman. There's a gospel thing on 'Eyeball Kid', and some Balinese samples.

The Eyeball Kid(9) is making his second appearance: you namechecked him on Bone Machine's 'Such A Scream'.

I did? I don't remember that. Anyway, that's like a little showbiz tune, about the perils of the business. "You got to have a manager, that's what it's all about..." If you wanna get into music, someone will eventually say that to you.

You've said you were on your own a lot as a kid. Was that solitude important to your development?

I guess most entertainers are, on a certain level, part of the freak show. And most of them have some kind of wounding early on, either a death in the family, or a break-up of the family unit, and it sends them off on some journey where they find themselves kneeling by a jukebox, praying to Ray Charles. Or you're out looking for your dad, who left the family when you were nine, and you know he drives a station wagon and that's all you've got to go on, and in some way you're gonna become a big sensation and be on the cover of Life magazine and it'll somehow be this cathartic vindication or restitution.

Can you recall an epiphanic moment that set you off in the direction of becoming a musician?

I had a friend who was an ambulance driver, and he gave me a stethoscope, and I used to sit in a dark room by myself, and I'd take the membrane of the stethoscope and put it in the hole in my guitar. And that was really the beginning of my hearing music very close up seeing the hair on the music. And I think maybe that was some kind of seminal moment for me. I would have been about 16 or 17.

Do your early memories of Mexico still filter through your songs?

As much as anyone's memories do. I'll start out with pictures of things that have happened, then slowly they start to get more like paintings, and then maybe they just turn into shapes. Then slowly they fade to black, I guess. My dad taught Spanish all his life, so we went down to Mexico. Used to go down there to get my haircut a lot. And that's when I started to develop this opinion that there was something Christ-like about beggars. See a guy with no legs on a skateboard, mud streets, dogs, church bells going. I'd say, yeah, these experiences are still with me at some level.

Had things been different, might you have resigned yourself simply to living in National City, working at Napoleone's Pizza House, or whatever might have followed from that?

Sure, yeah. I'm still not convinced that I made the right decision. Who's to say, y'know? I go back and forth. I think I'm, like, doing this children's work. "What do you do?" "I make up songs." "Uh, OK, we could use one of those, but right now what we actually need is a surgeon." In terms of the larger view, there's no question that entertainment is important. But there are other things I wish I knew how to do that I don't.

There's this received notion that the '60s somehow bypassed you that you weren't interested in The Beatles or the radical spirit of the times.

Yeah, but it has to do with when you choose to enjoy these things. I'm just suspicious of large groups of people going anywhere together. I don't know why, I always have been. If there 30,000 people going to see some event, I'm suspicious of it. But the thing about a record is that it's a record: if you don't want to listen to it right now, don't listen. Listen in 30 years. You know, in the tombs of the Pharoahs they've found jars of honey, and the honey is just as fresh as the day they collected it. In a sense, you put a record on and there it is. There's that moment they captured. I mean, I just heard Kicks by Paul Revere and the Raiders on my way here, and that's a cool song! Wild Thing. Louie Louie. I heard Son of a Preacher Man the other day, and it just killed me. There's a point in the song where she just kind of whispers, "The only one who could ever love me", really smoky and low that's a sexy song! Hey, it's all out there.

When you finally discovered jazz and Jack Kerouac, around 1968, did you bond with other people through that, or was it a fairly solitary passion?

Oh yeah, it's just like when you buy a record and you hold it under your arm and make sure everyone can see the title of it. It's about identity, I guess. I felt I had discovered something that was so rich, and I would have worn it on the top of my head if I could've. I mean, I incorporated it into what I was.

How long did you work at the pizza place?(10)

I was there from when I was about 14 to when I was 19.

You were writing songs by the time you were about 19, I assume.

Starting to. I don't know if they were really songs. Mostly they parodied existing songs with obscene lyrics. That's what most people do, or that's what I did.

What was you life like then?

Well, it was a sailor town. The military was the centre of life. Everyone I knew came from navy families. My dad was gone for good, and their dads were in the Philippines for eight months at a time. So nobody had dads around. I remember living next door to a family, woman's name was Buzz Fletterjohn. She was, like six feet nine with no fingernails, husband was chief bosun in the navy and I think he was in Guam for a year and a half. She raised four boys, and their backyard was this strange place with carp in the bathtub. I was never allowed in Buzz Fletterjohn's yard, that was the big thing. We actually made up a song about it, but it didn't wind up on the record. Then we had a big dog, a boxer, and whenever our dog got out, all the kids in the neighbourhood would shout, "Pepper's out!! Pepper's out!!" It was like an air-raid warning. All the kids would scramble and hide in the trees. At a certain age, you realised the cool thing about San Diego was that there were a lot of tattoo parlours, and when you were ready, you knew exactly where you were going. I was talking to Paul Ruebens [Pee-Wee Herman] about it the other day. He said that he grew up in Sarasota, Florida, and hated it, but when he went one night to a diner, and the whole joint was populated by circus people, and he went, Oh, what a cool place to live. So there's a certain place where you make that identification with your community. And then the next thing it's like, Jeez, I gotta get the hell out of here!

But you got your tattoo...

Oh, yeah, I got a map of Easter Island on my back. And I have the full menu from Napoleone's Pizza House(10) on my stomach. After awhile they dispensed with the menus: they'd send me out, and I'd take off my shirt and stand by the tables.

What were the first songs you sang publicly?

Oh god. I'm not gonna tell you the truth about this. I did an all-Schoenberg programme for the first year. no, I played Hit the Road Jack, Are You Lonesome Tonight. It was pretty lame, really, but I knew at a certain point that I had to get into show business as soon as possible. I probably should have changed my name, but by then it was too late.

What prompted the switch from acoustic guitar to piano?

Somebody gave me a piano. Put it out in the garage. I played and I learned songs, and then I memorised songs and pretended to be reading the notes. I'd even get a little closer to the sheet music. I realised that I was good at memorising: if I heard a song I could play it. And I still pretty much can do that. If I hear a particular change or something on somebody else's song, I can go to the piano and find it.

Was Randy Newman an influence?

Yeah, because he was always like a Brill Building guy. He was part of that whole tradition: you go siddown in a room and you write songs all day. Then you get these runners and you get the songs out to Ray Charles or Dusty Springfield. I mean, that's what Joni Mitchell was doing too, she was sitting in a room writing songs, it was just the perception of yourself as a songwriter was changing. And I caught that wave, the songwriters garnering understanding and sympathy and encouragement. Up until that point, who cared who wrote the songs? Just, you know, kill me with it. Nobody made a distinction between a song Elvis sang and a song Elvis wrote. Did he write it? Does it matter? No. And then everybody kind of wore that around. For awhile there anybody who wrote and performed their own songs could get a deal. Anybody. So I came in on that.

On the first album, Closing Time, one could almost be forgiven for thinking, here's another member of the Asylum gang: Joni, The Eagles, Jackson Browne, J.D. Souther.

They always try to create scenes, just making connections so that they can create circuitry. It all has to do with demographics and who likes what: if you like that, you'll like this. If you like hairdryers, you'll like water-heaters. Then you try to distinguish yourself in some way, which is essential- you find your little niche. When you make your first record, you think, That's all I wanna do is make a record. Then you make a record and you realize, Now I'm one of a hundred thousand people who have records out, OK, now what? Maybe I outta shave my head.

To what extent was the Tom Waits persona already in place with Closing Time? How much had you learned from Lord Buckley and Lenny Bruce at that point?

I don't know. You take a little bit from here and a little bit from there. Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue. My dad's hat, my mom's underwear, my brother's motorcycle, my sister's pool cue. and there you go.

When did you know you'd found your voice?

After I got my grandma's purse.

How important was it meeting Bones Howe - somebody who understood what you wanted to do?

Well, Jerry Yester [producer of Closing Time] was a great producer- the first guy whose house I ever went to and found a pump organ. Bones I met. I don't remember how I met Bones(11). In those days, nobody would even think of sending you into the studio without a producer. In their mind, they gave you 30 grand, you might disappear to the Philippines and they never see you again. They're not giving you 30 grand, they're giving this guy who plays tennis and wears sweaters and lives in a big house, they're giving him the money and he's paying for everything. Just show up on time and stay out of jail. Bones and I did a lot of 2-track records. Even though there were more than four tracks available, I was paranoid about it. Once I left town and they added strings and chick singers and all this, I was like, "I don't like that. Let's just do it so it's done." Bones had a background in jazz, and he'd done a lot of records like that anyway. He's a gentleman. We've had our conflicts. He loves the mythology of the music scene. He'll say, "I stood right here with Elvis Presley." A lotta stories. See, I was not really able to articulate what I wanted to do. Ended up putting strings on everything. My voice has this cracked quality, so let's put strings behind it. It was kind of like taking a painting that's made out of mud and putting a real expensive frame around it. It was about as deep as that. And I look back later and think, well, I could have done a lot of different things, but I didn't have the wherewithal.

You regret all those string arrangements?

Well, it's MSG(12): enough already. Enough with the corn starch.

I always thought you were in this unique position of having one foot in the Elliot Roberts-Asylum camp and the other in the Herb Cohen-Bizarre camp. You had a song covered by the Eagles, but you went on tour supporting Frank Zappa.

I was always rather intimidated by Frank, 'cos he was like some type of baron. There was so much mythology around him, and he had such confidence. Tremendous leadership and vision. When I toured with him, it was not well thought-out. It was like your dad saying, "Why don't you go to the shooting range with your brother Earl?" And I was like, I don't really want to, I might get hurt. And I did get hurt. I went out and subjected myself to all of this intimidating criticism from an audience that was not my own. Frank was funny. He'd just say: "How were they out there?" He was using me to take the temperature, sticking me up the butt of the cow and pulling me out. Kind of funny in retrospect. I fit in, in the sense that I was eccentric. Went out every night, go my 40 minutes. I still have nightmares about it. Frank shows up in my dreams, asking me how the crowd was. I have dreams where the piano is catching fire and the legs are falling off and the audience is coming at me with torches and dragging me away and beating me with sticks. so it was a good experience.

How do you remember the Troubadour in LA?(13)

That was the big place to play. They'd put a big picture of you in the window. In those days, if you sold out at the Troubadour, that was it. People weren't playing sports facilities. At the Troubadour, they announce your name and picked you up with a spotlight at the cigarette machine, and they'd walk you to the stage with the light. It was the coolest. The owner, Doug Weston, would go out on-stage naked and recite The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. He'd have guys on acid who wanted to tell stories. It was like Ed Sullivan, without Ed. Anyone could get up. It was very thrilling, though, because you would find people who'd hitchhiked to this sport for their 20 minutes.

To what extent did the persona you created on The Heart of Saturday Night merge with the real Tom Waits?

You mean, am I Frank Sinatra or am I Jimi Hendrix? Or am I Jimi Sinatra? It's a ventriloquist act, everybody one.

But some people are more honest about it being an 'act' than others. We aren't supposed to think Neil Young is doing an 'act'.

I don't know if honesty is an issue in show business. People don't care whether you're telling the truth or not, they just want to be told something they don't already know. Make me laugh or make me cry, it doesn't matter. If you're watching a really bad movie and somebody turns to you and says, "You know, this is a true story," does it improve the film in any way? Not really. It's a bad movie.

Let me put it like this. The person that people thought they were seeing on-stage- how much of a true story was that?

I don't know. How many Germans does it take to screw in a lightbulb? How many sperms are in a single ejaculation? Four hundred million. And it's hard to believe that all of us are the ones that won.

In 1975, when Born to Run and Nighthawks at the Diner came out, did you ever look at Bruce Springsteen and think, Gee, maybe I should have done that? Later songs like Downtown Train sort of lean in that direction, as does the new album's Hold On, for that matter. Bruce could easily sing that one.

I saw Bruce in Philadelphia when I was about 25, and he killed me- just killed me. I don't know, nobody sits down to write a hit record. I got to a point where I became more eccentric- my songs and my world view. And I started using experimental instruments and ethnic instruments and trying to create some new forms for myself. Using found sounds and so forth. Everybody's on their own road, and I don't know where it's going.

Did you feel, as many of your fans did and do, that Small Change was the crowning moment of your beatnik-glory-meets-Hollywood-noir period?

Well, gee. I'd say there's probably more songs off that record that I continued to play on the road, and that endured. Some songs you may write and record but you never sing them again. Others you sing 'em every night and try and figure out what they mean. Tom Traubert's Blues(14) was certainly one of those songs I continued to sing, and in fact, close my show with.

Foreign Affairs had extraordinary songs like Burma Shave and Potter's Field on it, but one sensed you were growing tired of working in that musical vein.

I guess I was. I was still in the rhythm of making a record, going out on the road for eight months, coming home and making another record, living in hotels. That's kind of what my life was in those days. I was trying to find some new channel or breakthrough for myself.

Would it be fair to say with Blue Valentine and Heartattack and Vine you were inching your way towards the sound of Swordfishtrombones? I'm thinking, for example, of the heavy blues guitar riff on Heartattack itself.

Well, when you're working with the same producer and you're kind of collaborating on the records, it's a little harder to go your own way. You kind of wanna take everybody with you. For me, eventually I just wanted to make a clean break. Both those records I did with Bones, and I as kind of rebelling against this established way of recording that I'd developed with him. And I was still with Herbie Cohen(15) in this tight little world.

Were you happy or unhappy at that point?

I don't know if I'd call it particularly unhappy, but I was at the end of a cycle there.

Were you also tiring of the whole Tropicana lifestyle at that point?

At some point there, I moved to New York and then came back to start working at Zoetrope Studios and writing songs for One From the Heart. Then I took a break from that and got in a humbug over my whole thing with the picture there. For a brief spell I moved out of my office at Zoetrope and went and wrote a record, and that was Heartattack and Vine. And by then I had Kathleen.

Is it fair to say that the One From the Heart soundtrack drew a curtain on that very melancholy Tin Pan Alley style?

I think by the time Francis called and asked me to write those songs, I had really decided I was gonna move away from that lounge thing. He said he wanted a "lounge operetta," and I was thinking, well, you're about a couple of years too late. All that was coming to a close for me, so I had to go on and bring it all back, It was like growing up and hitting the roof. I kept growing and kept banging into the roof, because you have this image that other people have of you, based on what you've put out there so far and how they define you and want they want from you. It's difficult when you try to make some kind of turn or a change in the weather for yourself. You also have to bring with you the perceptions of your audience.

There's always been this dialectic on your albums between hard and soft, grit and schmaltz, and it's still there on Mule Variations. For instance, you come straight out of the demented Eyeball Kid into the very delicate Picture in a Frame, the out of the completely crazed Filipino Box Spring Hog into the tender Take It with Me. Is that dialectic indicative of some split inside you?

I don't know if I've reconciled those things. I guess I would like to try and find some way to put those things together, instead of putting them end-to-end. Find a way to smash one into another, or mutate it in some way. I guess they're different facets of things I'm drawn to. Or maybe it's just, you put your fist through the wall and then you apologize- the alcoholic cycle! I don't know, I think Swordfishtrombones was trying to channel some of that rage through the music. But I think maybe it goes back to dances when I was a teenager. You know, they'd do four or five fast songs and then it was a slow dance when you'd get to ask the girls to dance. And that cycle of music, I think, always stayed with me. It really has to do with the heart rate, and then songs that are slower, and I guess I've always made a distinction between those.

What drew you to acting?

Well, I wasn't drawn to it, I was asked. I don't know if I really think of myself as an actor. I like doing it, but there's a difference between being an actor and doing some acting.

Tell me about the "perverted doctor" you play in the forthcoming film Mystery Men.

Perverted? I don't know. There's a scene with a woman in her nineties at a rest home where we watch television and I make advances, but I wouldn't necessarily call that perverted. Dr. Heller likes older women, and I guess it's so radically different from the Hollywood cycle of older men with younger women. What's really perverted is these old- timers going and picking up these young gals. I respect maturity and longevity.

You've said that One from the Heart helped to discipline you as a songwriter. Did that discipline carry through to the Island records?

I think I always tried to imagine for those guys who sat in an office all day and wrote songs. I always fantasized about what that might have been like, and I really had my chance to do that on One from the Heart.

Would you ever return to the kind of lush orchestrations that were so prominent on your earlier records?

Uh, yeah. I'm not saying I'm not going to ever use a string section again. I think I exhausted that whole genre and I've gone off in a whole different direction now.

How much impact did New York have on the sound of Swordfishtrombones and Raindogs? Some of the imagery in the songs on those albums was obviously affected by that environment.

Any place you move is going to have some effect. I was exposed to a kind of melange of sounds out there, because I went to clubs more. It's rather oppresssive, I think. I'd write and go down to the Westbeth building [Greenwich Village,] where I shared a room with John Lurie and his brother Evan. We'd go down there at night and write songs. It was quiet at night. I'd work 'til late and come home. The thing when you have kids is that you can stay up 'til five in the morning, but you still gonna get up and have to feed them.

You've said that Victor Feldman [English-born vibraphonist] had a lot to do with the sound of Swordfishtrombones, although as I understand it you were already fully aware of people like Harry Partch by that point.

I don't know, a lot of credit has to do to Kathleen, because that record was really the first thing I decided to do without an outside producer. It was really Kathleen that said, "Look, you can do this. You know, I'd broken off with Herbie, and we were managing my career at that point, and there were a lot of decisions to make. I mean, I thought I was a millionaire, and it turned out that I had, like 20 bucks. And what followed was a lot of court battles, and it was a difficult ride for both of us, particularly being newly weds. At the same time, it was exciting, because I had never been in a studio without a producer. I came from that whole school where an artist needs a producer. You know, they know more than I do, I don't know anything about the board. I was really old-fashioned that way. And Kathleen listened to my records and she knew I was interested in a lot of diverse musical styles that I'd never explored myself on my own record. So she started talking to me about that- you know, "You can do that." She's a great DJ, and she started playing a lot of records for me. I'd never thought of myself being able to go in and have the full responsibility for the end result of each song. She really co-produced that record with me, though she didn't get credit. She was the spark and the feed. The seminal idea for that record really came from Kathleen. So it was scary and exciting, but it was like, "Well, OK, let's find an engineer." And I found Biff Dawes, and he was into it. And I knew a lot of musicians. So I went in and did four songs, and I went and played them to Joe Smith at Elektra-Asylum. And he didn't know what to make of it, and at that point I was kind of dropped from the label. Then [Chris] Blackwell heard the record and picked it up. That was kind of a bumpy ride there for a while.

You must have felt liberated by the time you'd come out the other side.

A lot more self-esteem, I think. We'd done something on our own. It just felt more honest. I was trying to find music that felt more like the people that were in the songs, rather than everybody being kind of dressed up in the same outfit. The people in my earlier songs might have had unique things to say and have come from diverse backgrounds, but they all looked the same.

Would you ever attempt anything as ambitious as the Steppenwolf Theater Company production of Frank's Wild Years again?

Well, you have to be a little foolish to do something because a play takes a lot of energy- emotionally, financially. And the other thing is that it only lives when you're in it. But Steppenwolf was the right way to go. First person we approached was Robert Wilson, and he didn't know what to make of it. Of course, later I came to work with him on The Black Rider and Alice in Wonderland.

How did you make the selection on the Island anthology Beautiful Maladies? It must have been hard to leave out things like 'Blind Love'.

We'd already started writing Mule Variations, so we had to kind of stop and put that together. That was a little hard, because we had some forward momentum and then we had slam on the breaks. It was hard to get excited about it, really, because they're all old songs.

Could you have written songs like Bone Machine's Murder in the Red Barn if you hadn't moved to the country?

I buy the local papers every day, and they are full of car wrecks and. I guess it all depends on what it is in the paper that attracts you. I'm always drawn to these terrible stories. I don't know why. Black Irish? You know, my wife is the same way, she comes from an Irish family and she's drawn to the shadows and the darkness. Murder in the Red Barn is just one of those stories, like an old Flannery O'Connor story. My favorite line is, "There's always some killin' you gotta do around the farm." and it's true.

How much of a homebody have you become in recent years?

Gee, I don't know. That sounds like a loaded question. If I say no, I'll get into trouble with my family, and if I say yes I get in trouble with everybody else. You know, I live in a house with my wife and a lotta kids and dogs, and I have to fight for every inch of ground I get.

Do your songs stand up on the printed page as writing? Does 'Potter's Field', say, look good in print?

Oh gee, it looks like I got carried away. All these things are songs. It's nice when people say they like the words, or the songs work by themselves as lyrics, but that wasn't really the way they were created.

Did 'The Black Rider' grow out of an interest in that German cabaret style? Were you already interested in that style before you did What Keeps Mankind Alive on Hal Wilner's Kurt Weill album?

That macarbe, dissonant style, yeah. See, when I hear Weill I hear a lot of anger in those songs. I remember the first time that I heard that Peggy Lee tune, Is That All There Is?, I identified with that. (Sings.) "Is that all there is? If that's all there is, then let's keep dancing." So you just find different things that you feel your voice is suited to. I didn't really know that much about Kurt Weill until people started saying, "Hey, he must be listening to a lot of Kurt Weill." I thought, I better go find out who this guy is. I started listening to The Happy End, and the Threepenny Opera and Mahagonny and all that really expressionistic music.

How did you get on with William Burroughs when you collaborated on The Black Rider?

Well, we all went to meet William in Lawrence [Kansas.] Greg Cohen and Robert Wilson and myself. And we talked about this whole thing. It was very exciting, really. It felt like a literary summit. Burroughs took pictures of everyone standing on the porch. Took me out into the garage and showed me his shotgun paintings. Showed me the garden. Around three o'clock he started fondling his wristwatch as we got closer to cocktail hour. He was very learned and serious. Obviously an authority on a wide variety of topics. Knew a lot about snakes, insects, firearms.

Had he been an influence on you the way that Kerouac was?

Oh, course, yeah. He was Bull Lee in On the Road. He was the one that I guess was more like Mark Twain with an edge. He was more suited to the whole notion of the country having some type of alter ego. He seemed to be ideally suited to the position of poet laureate. He seemed to have an overview, and one of maturity and cynicism. I've heard a lot of the stuff he did with Hal Willner. The Thanksgiving Prayer and all that stuff. It just really killed me. He had a strongly developed sense of irony, and I guess that's really at the heart of the American experience. If you read the papers over the years, you have to see that there's something very ironic about everything.

You've said that you tend to "bury" directly autobiographical stuff. What about Who Are You? Should we know who that's about?

Gee, I dunno. I think it's better if you don't. The stories behind most songs are less interesting than the songs themselves. So you say, "Hey, this is about Jackie Kennedy." And it's, "Oh, wow." Then you say, "No, I was just kidding, it's about Nancy Reagan." It's a different song now. In fact, all my songs are about Nancy Reagan.

One last question. What or where is Manzanita?(16)

Manzanita is a tree. Everything around the Sacramento River Valley seems to be named after Manzanita: Manzanita School, Manzanita Market, Manzanita Road. It's gnarled, twisted, blood-red wood.

Barney Hoskyns 1998

Notes:

(1) Eddie Izzard: Waits and Izzard had just got aquainted on the set of "Mystery Men". Mystery Men (1999). Movie directed by Kinka Usher. TW: actor. Plays weapons designer Dr. A. Heller.

(2) A 1967 model he totalled last year: unknown/ unidentified incident

(3) West Hollywood's notorious Tropicana Motel: Further reading: Tropicana Motel.

(4) The last time I met Waits: Interview "The Marlowe Of The Ivories", New Musical Express magazine (UK), by Barney Hoskyns. May 25, 1985

(5) The Systems:

- Tom Waits (1973): "Yeah, I guess so, I couldn't think of anything else I really wanted to be, seems to be today nobody wants to be anything but, nobody wants to be a baseball player anymore or anything - everybody wants to be a rock n roll star. I was always real interested in music, it never really struck me to write until I guess about the late 60's, about '68 or '69 I started writing, up until then I just listened to a lot of music, played in school orchestras, played trumpet in elementary school, junior high, high school, went through all that and hung around with some friends of mine that played classical piano and picked up a few little licks here and there, played guitar and stumbled on the Heritage - and actually the first real songwriter I really saw and really got enthused about was Jack Tempchin and that was in about 1968 at the Candy Company on El Cajon Boulevard, he was playing on the bill with Lightning Hopkins and he was real casual and everything, it was just something I wanted to try my hand at, so I tried my hand at it, I don't know, I guess you get better as you go along, the more music you listen to and the more perceptive you become towards melody and lyric and all. The only place really to play in San Diego were folk clubs. I used to go to a lot of dances. I played in a band in junior high called The Systems... I played rhythm guitar and sang. I listened to a lot of black artists, quite a few black artists. I had a real interest in that - James Brown and the Flames were real big, I went to O'Farrell Junior High School, all black junior high school, and I went out to Balboa(?) and saw James Brown - he knocked me out, man, when I was in 7th grade. So I've kept up on that scene too and I listen to as many different kinds of music as I can." (Source: "Folkscene 1973, with Howard and Roz Larman" (KPFK-FM 90.7). Date: Los Angeles/ USA. August 12, 1973)

- Tom Waits (1976): "I did a few rock things; I was in a group called the Systems, I was rhythm guitar and lead vocalist. We did Link Wray stuff. Hohman: Link Wray - that's the guy who made all those killer rock instrumentals back in the late '50s, Rumble, Rawhide, Comanche, The Swag. TW: Yeah, Rumble was his first hit. I've been trying to pin down Frank Zappa's guitar style for a long time and I think Link Wray is the closest I can get. I think Frank is trying to be Link Wray. We did stuff by the Ventures, too, a lot of instrumentals. I finally quit that band; we had a drummer with a harelip and a lead guitar player with a homemade guitar. Actually, there were only three of us, so in a sense we were sort of like pioneers." (Source: "Bitin' the green shiboda with Tom Waits". "Down Beat" magazine. Marv Hohman. Chicago. June 17, 1976)

- Dan Forte (1977): "Around this same time Waits formed his first group, soulfully named The Systems. "I played rhythm guitar and sang," he comments. "Rhythm and blues - a lot of black Hit Parade stuff, white kids trying to get that Motown sound. I went to an all-black junior high and was under certain social pressure. So I listened to what was around me." Tom dropped out of high school during his junior year, because he was already working by that time - not as a musician, but as a cook. Several years on the graveyard shift at an all-night diner in San Diego, besides providing him with what would become fuel for subsequent songs and stories, convinced him that there had to be a better medium through which to channel his energies and words. As he told the Los Angeles Times, "I knew when I was working there I was going to do something with it. I didn't know how, but I felt it every night." (Source: "Tom Waits - Offbeat Poet And Pianist". Contemporary Keyboard magazine, by Dan Forte. April, 1977)

- Tom Waits (2002): "Heck I don't know if it was a soul band. It was surf and soul. I played guitar and sang. In those days, you didn't play a lot of gigs. You'd play a dance every now and then. I knew I wanted to do something with music, but navigating that seems almost impossible. It's like digging through a wall with a spoon, and your only hope is that what's on the other side is digging with the same intensity towards you... The band was called the Systems. Up until that point, you know, I played the ukulele when I was a kid and I played a guitar - my dad gave me a guitar. There was always music in the house. Frank Sinatra, Harry Belafonte and Louis Armstrong and Mexican radio." (Source: "Tom Waits". SOMA magazine. July, 2002 by Mikel Jollett)

(6) Gravikords, Whirlies And Pyrophones (Experimental Musical Instruments). Sound Hound: Foreword by Tom Waits to Bart Hopkin's book/ CD: "Gravikords Whirlies & Pyrophones - Experimental Musical Instruments." Publisher: Ellipsis Arts. October, 1996. Read foreword: Sound Hound

(7) Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and I used to open shows for them in the old days:

(8) Wayne Kramer: another old goat on the Epitaph label. Further reading: Wayne Kramer official site

(9) The Eyeball Kid: further reading: The Eyeball Kid

(10) Napoleone's Pizza House: further reading: Napoleone Pizza House

(11) I don't remember how I met Bones: longtime friend, collaborator/ producer. Further reading: Who's Who?

- Jay S. Jacobs (2000): "Howe himself had seen the writing on the wall. He and Waits were clearly pulling in different directions. "After we did One from the Heart and the sound-track album came out" he recalls, "Tom and I sat down and had a glass of wine at Martoni's. He said, 'I'm trying to write the next record. The problem that I'm having is, I know you so well and everything that I write, I keep thinking to myself, I wonder if Bones is going to like this? Or, I can't write this tune because I don't think you'll like it.' I told him, 'Tom, I shouldn't have any influence on what you create. Yeah, we do know each other really well, and of course you know the things that I like.' He said, 'I really want to get away from composing on the piano, because I feel like I'm writing the same song over and over again'. While assuring Tom that he was in no such rut) Bones did concede that if he truly felt that way, there was no "more rational reason for two people to stop working together than this. So, we sort of shook hands and said, 'Okay, that's it.' I just told him, 'Look, if you ever want to make another record with me, you know the kind of records I'll make. Call me, and wherever I am, whatever I'm doing, I'll stop it and make a record with you.' Because that was really, really fun. I miss doing that with him. I've never found anybody I've enjoyed doing that with as much as Tom." So, over an amicable glass of wine, a long and fruitful partnership was dismantled. Howe adds that Kathleen played a role in the demise of the relationship, as well. "She really separated him from everybody in his past. And, frankly, it was time for that for Tom. Kathleen has been very good for him. He was never as wild as many people have said, but he was living in a motel and not really taking that good care of himself. It really was time. She separated him from everybody. Unfortunately, I was in the cut. I was from the past." (Source: "Wild Years, The Music and Myth of Tom Waits". Jay S. Jacobs, 2000)

(12) MSG: "MSG is a flavor enhancer which has been used effectively for nearly a century to bring out the best flavor of foods. Its principal component is an amino acid called glutamic acid or glutamate. Glutamate is found naturally in protein-containing foods such as meat, vegetables, poultry and milk. The human body also produces glutamate naturally in large amounts. The muscles, brain and other body organs contain about four pounds of glutamate, and human milk is rich in glutamate, compared to cow's milk, for example. Glutamate is found in two forms: "bound" glutamate (linked to other amino acids forming a protein molecule) and "free" glutamate (not linked to protein). Only free glutamate is effective in enhancing the flavor of food. Foods often used for their flavoring qualities, such as tomatoes and mushrooms, have high levels of naturally occurring free glutamate." (Source: "MSG Facts". The Glutamate Association, Washington, DC)

(13) The Troubadour in LA: Monday's "hootnights" at Doug Weston's Troubadour (located at: 9081 Santa Monica Blvd., West Hollywood) where Mr. Waits got his break into show business during the summer of 1971. Further reading: The Troubadour.

(14) Tom Traubert's Blues: further reading: Tom Traubert's Blues

(15) Herbie Cohen: rockmanager and label owner Herb Cohen. Further reading: Copyright

(16) Manzanita: Manzanita n.: Any of various western North American evergreen shrubs (genus Arctostaphylos) of the heath family (Tom Waits Digest: Websters Dictionary) One can imagine a cross grown out of the red wood of the Manzanita.

- As mentioned in "Pony" (Mule Variations, 1999): "I run my race with Burnt Face Jake gave him a Manzanita cross" and "Murder In The Red Barn" (Bone Machine, 1992): "The watchman said to Reba the Loon Was that Pale at Manzanita, was it Blind Bob the Coon?"