|

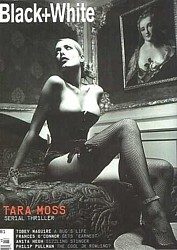

Title: Make Mine A Double Source: Black + White magazine (USA). Issue 61. June/ July 2002. By Clare Barker. Photography by Anton Corbijn. Transcription by "Pieter from Holland" as published on the Tom Waits Library. Thanks to Dorene LaLonde for donating magazine Date: telephone interview, early 2002 Keywords: Alice/ Blood Money, Poor Edward, Table Top Joe Magazine front cover: Black + White issue 61. June/ July 2002 |

| Accompanying picture |

Make Mine A Double

Misery loves company. So Tom Waits has come out with two new albums at once - One for the misfits, the other for the freaks

Text: Clare Barker

Photography: Anton Corbijn

For years, Tom Waits told journalists he was born in the back of a cab with the meter still running. He's the smart-mouthed drunk in the beat-up suit, the gravel-voiced, piano-playing poet with the sardonic scowl. In a film career that has spanned two decades, he has played down-and-outs, drinkers, convicts and lunatics. As a musician, he has written operas, mastered every odd and forgotten instrument in the book and delivered 20 albums Yet, for the most part, Waits has eluded mainstream success.

And it's hardly surprising. There is nothing radio friendly about a polka for the damned. Waits' love songs that tell of betrayal, suicide and madness, destructive fairytales that resolutely refuse to be easy on the ear. On Alice, which together with Blood Money forms the pair of albums he released in May, Waits sings a dark lullaby to Lewis Carroll's impossible love for his young heroine:

"How does the ocean rock the boat?/ How did the razor find my throat? / All the strings that hold me here/ Are tangled up around the pier/ And so a secret kiss/ Brings madness with the bliss/ And I will think of this/ When I'm dead in my grave."

Later on the album we meet "Table Top Joe", a cabaret performer born without the lower half of his body, and "Poor Edward", a man driven insane by his deformity:

"Did you hear the news about Edward/ On the back of his head he had another face/ Was it a woman's face?/ Or a young girl?/ ... The face could laugh and cry/ It was his devil twin/ At night she spoke to him."

"Don't you have the same thing going yourself?" he growls down the line from his home in Santa Rosa, California. "You write about things that you understand and have compassion for. You don't write about worlds that you don't inhabit yourself."

In 1949, Wafts was born (with one face and both legs) to schoolteacher parents. They divorced when he was 10 and he led an itinerant childhood around California with his mother and two sisters. The teenage Waits dropped out of high school to work in pizza shops and clubs. He eventually ended up as a doorman at The Heritage nightclub in San Diego, where he took to the stage between gigs mixing spoken word and song. He began playing Monday nights at the LA Troubadour, where he was spotted and later signed by Herb Cohen from Asylum Records.

His first two albums, Closing Time and The Heart Of Saturday Night, established Waits as the common man's poet, singing on behalf of truck drivers, factory workers, hobos and late-night hoodlums. He read Bukowski and Ginsberg and moved into the Tropicana Hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard with songwriter and beat poetess, Rickie Lee Jones.

Waits then had a modicum of commercial success, opening shows for the likes of Frank Zappa and playing at Ronnie Scott's in London, but by the time Small Change came along in 1976 featuring "Bad Liver And A Broken Heart" and "The Piano Has Been Drinking (Not Me)" -as a performer, he had become a caricature of himself. Tom Waits: hard drinker, chain smoker, lonesome barfly. The man who once told a journalist from Time magazine(1) that he kept his piano in his kitchen because he had no use for the icebox and "the stove is just a large cigarette lighter".

In 1979, Waits met scriptwriter Kathleen Brennan. "It was love at first sight, no question of it," he recalls. "It was New Year's Eve in LA and they were raffling off a '69 Caddy. There was a band playing called The Sandhogs, another group on the bill called The Spastic Colon. We met. She was all dressed in black. I was leaving town the next day going to New York, never to return. But never say never."

Brennan's arrival marked a shift in direction for Waits. His eighth album, Swordfishtrombones, was an experimental record incorporating the bizarre instrumentation he would become known for. He started writing songs with Brennan, and albums such as Rain Dogs, Bone Machine and the Grammy-winning Mule Variations followed.

Brennan co-wrote both the Alice and Blood Money albums, the latter of which is based on the harrowing 19th-century German stage play, Woyzech. The records feel otherworldly, inhabiting some place between day and night where an off-kilter waltz fits in with bar room jazz. Waits moans and growls. He plays on words and the Stroh violin, the pneumatic calliope and a giant seedpod from Indonesia.

"You trust someone's opinion with a road map or a recipe, you may as well trust them with a piece of music," says Waits of his partner in song. "She's got a background in opera, she's got her pilot's license, she used to work in the circus when she was a kid." This is beginning to sound like the tall tale of the taxicab birth. Waits has a reputation for embellishing the details of his past to suit his point - in this case, that Brennan is at least as complex and creative as he is. "She wanted to be a nun, but she gave that up. She's originally from Illinois, her family is from Indiana, right out in the middle of the country where everything is flat and all you can do is dream. So I think I'm the conservative one of both of us. She's much more adventurous. I keep her from floating off."

And perhaps Waits is, if not conservative, at least grounded. He has been married to Brennan since 1980 and they have three children. Now a ravaged 52, he looks as if he might be a decade older; you could hang a coat hook from the grooves in his forehead. But his is a stately crumbling, having nothing in common with the addled, rock star disintegration of Richards or Jagger. Waits has grown into his craggy face and wayward hair, finally seems comfortable in his old fashioned suits.

His source material is becoming increasingly highbrow, from the William Burroughs operetta The Black Rider to Woyzech. And he can't be badly off. It's hard to imagine a Grammy winner fumbling for a nickel beneath an old park bench. Hell, he even has a music festival named in his honour, the annual Waitstock held outside New York.(2)

So where does that leave Tom Waits' fascination with the underclass? He has not switched to themes of health, wealth and happiness; his songs are still peopled with derelicts and freaks like "Poor Edward".

"That song is about Edward Mordake, one of those early last century characters," he explains. "It's a true story about a man who had a woman's face on the back of his head. It's kind of a sad story, it eventually drove him to madness and suicide, so it has an operatic feeling to it. I tried to get into the mind of that man, but at the same time it's a metaphor for any kind obsession or compulsion that might be impossible to control."

He might claim that, like Jane Austen before him, he writes what he knows, but it seems far more likely that Tom Waits has cut himself free from his own experience - to become the conjurer, the circus performer, the fairytale author. "I tried to make it music from another world, songs from a distant place inside," he says of his new records.

"I think music, or going into show business in any form, is like running off to join the circus. It seems like most people who have things about them that are peculiar or unusual or imbalanced, that make them unique or special, are drawn to entertainment. At one point or another, you're going to say: Maybe I could do something with this."

For example, by making a tall tale out of a legless man.

"Table Top Joe is a nickname that I gave a real life character. His name is Johnny Eck. He had a twin brother who was of normal height and size, they used to have a magic act on stage. His brother would saw Johnny in half. Johnny walked on his hands, he was about two feet tall, but he was an excellent pianist and he had his own orchestra. He was a sideshow attraction."

Waits would have you believe he met Johnny Eck in Coney Island or maybe a San Diego pizza shop, at a travelling circus or even in the back of a cab with the meter still running, Is Johnny still around?

"He's long gone. He lives only in my memory."

Alice and Blood Money are out now through Shock Records

Notes:

(1) A journalist from Time magazine: article unknown. Earliest known mention: Dan Forte (April, 1977): "Waits' Steinway upright does indeed occupy the far corner of his kitchen. "You'll notice what I had to go through in order to get it in," he says, leading the way. "First of all, I just could barely get it through the threshold. Then I had to saw off the draining board." He motions to the ragged edge of the sink's counter. "My next obstacle," he continues, "was a broom closet. Of course, I made short order of that son-of-a-bitch." The splintered-off corner of the room's entrance testifies to the validity of his statement." (Source: "Tom Waits - Offbeat Poet And Pianist". Contemporary Keyboard magazine, by Dan Forte. April, 1977)

(2) Waitstock held outside New York: Waitsstock (Poughkeepsie/ USA). Further reading: Waitstock