|

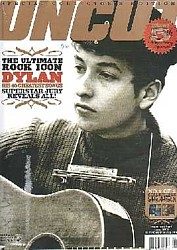

Title: Everything Goes To Hell Source: Uncut 5th Anniversary Special. Take 61, June 2002 by Gavin Martin. Transcription by "Pieter from Holland" as published on the Tom Waits Library Date: Flamingo Resort Hotel & Conference Center 2777 Fourth Street, Santa Rosa, CA. February/ March. Published: May, 2002 Keywords: Alice/ Blood Money, Paul Auster, Mel Clay, Charley Patton, Robert Wilson, Kathleen, James Brown, Bob Dylan, Frank Zappa Magazine front cover: Uncut 5th Anniversary Special. Take 61, June 2002 |

Everything Goes To Hell

He may have spent much of the past decade watching his children grow and sobering himself up after years in thrall to the bottle, but on the evidence of his brilliant new albums, Alice and Blood Money(1), Tom Waits remains the undisputed laureate of all things dark and blasted, by Gavin Martin

On a sunny Californian morning, Tom Waits pulls his family-size Suburban Chevrolet into the car park of Santa Rosa's Flamingo Hotel and begins to unpack the trunk. Every day for the next week, he'll make the 30-minute drive from his home to the hotel to meet the international press, and he's brought along some effects to give the room a personalised touch. There's a small library of books, including various encyclopedias filled with Weird, Wonderful and Exotic facts, Paul Auster's My Father Was God (2)and Mel Clay's strikingly titled Jazz-Jail And God(3), a soundbox and a selection of CDs. Pride of place is given to The Worlds Of Charley Patton CD box set(4). When I arrive for my allotted 60 minutes, he's just finished lunch and is making a brew on the kitchenette Mister Coffee machine. Springing round to offer a handshake, precariously balanced on beat-up biker boots but surprisingly agile for his 53 years, he signals towards the Patton box set. "Have you seen this? Oh boy, it's a killer," he says. "I've had three copies of it but I keep giving them away. Everybody knows Patton - well, that's not quite accurate. But maybe they will if I keep buying the box sets and giving them away," he laughs. "I first heard him when I was 18, playing coffee house and folk festivals. I was very curious about the evolution of American music and the migration of seeds and all that business." He pauses, then adds: "I guess there was something in that fat deep rich voice that taught me more than I could ever quantify."

The last time I interviewed Waits was in 1985(5), just as Rain Dogs - his first album since the classic Swordfishtrombones had signaled a fascinating sonic departure from the B-movie atmospherics, dime-store rhapsodies and lowlife jazz of his early career - was about to be released. The interview took place on a Sunday morning in a rundown New York diner. Tom was bleary-eyed, unshaven, breakfasting on dark beer and cigarettes. Part Bowery bum, part bohemian savant, he took pleasure in improvising answers that played fast and loose with the facts, determined to entertain as much as enlighten. He seemed immersed in the city, and Rain Dogs put an inspired spin on its colourful characters and junkshop musical polyglot. But he and his wife Kathleen Brennan had just become parents for the second time, and Tom figured the Big Apple was no place to raise children. "New York is like a weapon." he told me, "you live with all these contradictions and it's intense, sometimes unbearable. It's a place where the deadline to get a picture of the bum outside your apartment is more important than his deadline to get a place to sleep." In the years since, Waits has moved to LA, San Francisco and finally the place 30 minutes away that he now calls home. He's forsworn drink and cigarettes, won a landmark $2.4 million lawsuit against Frito Lay(6) for using a Waits soundalike in Dorito chip radio ads, and acted in several movies, notably alongside Lily Tomlin in Robert Altman's Short Cuts. Though he continued to add to his musical legacy with Bone Machine (1992) and The Black Rider (1993), for most of the Nineties he was a full-time father raising kids with Kathleen. I ask whether he didn't get the cabin fever out there with the family, not releasing any records between The Black Rider and 1999's Grammy-winning Mule Variations, by far the most commercially successful album of his career? Byway of a reply, he fumbles in his jacket pockets and produces a small plastic microphone with a built-in recording device. "Not at all. Y'see, you must remember toys are not for children," he grins. He spits a few human beat-box noises into the mic to demonstrate. Then, from an inside jacket pocket, he produces an identical microphone. He plays the recording on the first one back as he spits out a few more beats, and records the result with the second. Multi-tracked technology at its finest. "If you're a creative person you're always doing something creative," he laughs. "There's an old expression: 'The way you do anything is the way you do everything.' So if you're creative about how you make dinner, then you'll be creative about whatever else you do. So I didn't really feel like someone was stepping on my tail. I just thought I was looking out a different window. But music's what I love. I find myself doing it whether or not there's going to be any result or product at the end of it."

Dressed in a black suit, curly hair neatly coiffed and goatee finely trimmed, Waits is undoubtedly a wiser, more thoughtful, and indeed sober interviewee than the man I met 17 years ago. But once he sits down at the kitchen table to talk he displays a few traits that suggest he's not quite at ease. There's a tendency to mumble and speak with his hand over his mouth and, once he finds his train of thought, he rocks back and forth in his chair, hands wrapped around his torso, straitjacket-style. But he's unfailingly polite and modest, uneasy about acknowledging the considerable influence he's had since sounding the rallying call to "a world going on underground" on the opening track of Swordfishtrombones ("Underground"). "It's nice to feel that you're having some effect, but I don't want to put too much stock on it or put too much weight on my contribution," he cautions. "I'm not someone who has a lot of hit records. My effect is more subversive I guess." Waits' voyage into the undergrowth of Americana and worlds beyond has been unparalleled in the past 20 years. His first albums, Closing Time (1973) and The Heart Of Saturday Night (1974), saw him compared to Bruce Springsteen but where The Boss struck out for the heartland, Waits found teeming life in the margins. Over the years on his journey into bizarre, enchanted and terrifying lands, he's been joined by a cast of co-conspirators. His two new LPs, Alice and Blood Money, separate but simultaneous releases, initially grew out of collaborations with avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson (who also worked with Lou Reed on a production based around the work of Edgar Allen Poe). Waits' relationship with Wilson goes back to The Black Rider(7) (which also saw Waits collaborating with William Burroughs), and he talks about him with a mixture of awe and personal identification. "He's like a scientist, medical student or an architect - he has that quality when you first meet him. He also probably has an attention deficit disorder, dyslexia and probably a little compulsive disorder syndrome, too. I must have recognised aspects of myself in him. He seems almost autistic as he's compelled to communicate, but has the limits of certain known forms of communication, and he's gone far beyond in developing others. "In theatre, he's developed a whole language for himself and those he works with ... right down to the way he has people move. He's compelled to create a world where everyone conforms to his laws of physics. He has everyone move real slow, because you can't grasp the full drama of a movement onstage that happens in real time, it won't register with you. It makes you think about the simplest movement, the act of getting out of a chair or reaching for a glass. "When I met him I felt I was with an inventor, Alexander Graham Bell or one of those guys. He's a deep thinker, a man who chooses his words very carefully and is not to be trifled with. We found out we were very different, but there was something that that we both understood about each other, which was as a good thing. If you're too much alike, there's not much you can learn from each other."

Both Alice and Blood Money display a sense of wonder, intimacy and fearlessness in keeping with their instigators' theatre work. Just as significantly, they are the first records that are 50/50 collaborations between Waits and Kathleen Brennan. Brennan and her hometown were eulogised in one of Waits' simplest but most beautiful compositions, "Johnsburg, Illinois". A character bearing her name appears in Mule Variations' crazed barbecue party piece, "Filipino Box Spring Hog", sporting "a criminal underwear bra". Although she shuns the limelight ("She hates all this," shudders Waits, pointing at my mini disc recorder), her presence shines not just in his songs but in the man himself. "She does everything blood, spit and polish," he enthuses. "She has a great background in music and a great business head. She's fabulous, ominous and hilarious. And all for us." When they originally met, Brennan was a script editor at Zoetrope studios. Tom was penning what became the Oscar-nominated score for Coppola's One From The Heart. The album required him to write in a style be was trying to leave behind, and it was Brennan who helped him find the confidence, security and self-respect to follow his esoteric leanings and make the leap towards 1983's Swordfishtrombones. Their working relationship developed gradually.

"The love came first,' nods Waits, "but we used to play a game called Let's Go Get Lost. We'd drive into a town, and I would say, 'But, baby - I know this place like the back of my hand, I can't get lost: And she'd say, 'Oh hell you can't, turn here, now turn here. Now go back, now turn left, now go right again.' And we'd do that all night, until we got lost, and she'd say, 'See, I thought you knew this town?' Now you're getting somewhere, now you're lost. That's kind of a good metaphor for how we collaborate." The benefits of that collaboration shine through, polished to perfection, on ballads like "All The World Is Green" (from Blood Money), Waits' tender vocal giving delicate life to the gem-like images. "We do talk about what we're doing all the time. The way we work is like a quarrel that results in either blood or ink. You find you may not have known how you felt about a particular sound or issue or phrase or melody until you are challenged to expand or change it. If it's a successful collaboration, you end up with more things in there than occurred at the outside. But, hell, we got kids. Once you've raised kids together, you find songs come easy, actually."

Robert Wilson's original stage production of Alice - performed as an "avant-garde opera" in Hamburg in 1992 - centred on the relationship between Reverend Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll) and Alice Liddell, the girl who inspired both Alice In Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass. Blood Money, meanwhile, is based on Woyzeck, a play written in 1837 by the German poet Georg B�chner about a tormented 19th century Polish soldier, a fable previously filmed by Werner Herzog. "We were going to call the album Woyzeck, but it was thought nobody knew who he was," Waits explains. "Kathleen said, 'Let's call it Blood Money,' and that made sense. The guy's a lowly soldier who's offered money for medical experiments, which contribute to his loss of balance and sanity. His wife's been flirting with the drum major and one thing leads to another. It's kind of a sad tale, without explaining it in too much detail. "The songs aren't really a linear narrative; you couldn't understand the story from hearing them. They might have been part of a theatre piece to begin with, but if you are going to do a record it has to stand alone. You have to get beyond the original concept; it's like making a movie out of a book." Both albums are populated by compositions that draw from every era of Waits' music: Tin Pan Alley ballads, spoken-word reveries, cantankerous punk blues. In 1985, he told me the piano was "firewood far as I'm concerned. I've started peeling the boards off until there's nothing left but metal strings and ivory" But the new albums suggest he's at ease with all aspects of his past. "I'm drawn to melody as much as dissonance. I think both are completely valid," he nods, "but it as hard recording the two albums at the same time, using a lot of the same musicians and trying keep them sounding completely different." Even so, the contrast is striking. Alice is light and mournful, reflective and contemplative, while Blood Money is dark, angry and inflamed. Indeed, on the latter, songs like "Everything Goes To Hell" and "God's Away On Business" transcend their theatrical origins. They sound like anguished howls at the present state of the universe in general, and America in particular. "Who are the ones we've left in charge?/ Killers, thieves and lawyers," Waits thunders on "God's Away On business", his voice scorched and horrified. It's as if his woebegone character has legitimised and given a voice to his own sense of despair and outrage. "Possibly," he says. "It's real cathartic to rail and rant and stomp into a mic. It's kind of cleansing and feels good. There were a lot of preachers and teachers in my family. In fact, my father was more than a little disappointed when he found out I was going to be neither. It was like, 'We aren't going to be able to help you, then', Music wasn't the family business." The way Waits describes it, when he was growing up he had no option but to make music his business. A watershed experience was seeing James Brown And The Famous Flames in the early Sixties. "It was like you'd been dosed or taken a pill. I didn't recover my balance for weeks. When you're a teenager music is a whole other thing. You're emotionally fragile, and the music is for you; it's talking to you. It was like a revival meeting with an insane preacher at the pulpit talking in tongues. To have that and Bob Dylan, who I saw during the same period playing in a college gym, it set me reeling."

The Waits of Alice and Blood Money projects a magisterial reach across time and musical nuance. Sometimes the songs sound as if they've been rescued from a ghostly past - "Going back in time to locate something you can't find in the future," as he puts it. In his live show, unseen in Britain for 15 years, he assumes a range of identities, from hillbilly eccentric to Brechtian outcast. But he has had to fight to create his own artistic space. "On my first tours I had to open for Frank Zappa," he recalls. "I'd go out and get beer cans thrown at me, people spitting at me. I always felt like I was a rectal thermometer taking the temperature of the audience for Frank. I told myself, 'This is good for me; it's called paying your dues.' At least I wasn't driving a school bus or selling arms for a living. It was painful, but you move on, get your own band together and suddenly some other guy is your rectal thermometer." He's always been out of step with musical and cultural trends. When Haight-Ashbury was the place to be he was "looking for Bing Crosby records in the Salvation Army shop, anything I could call my own path outside the course my generation was taking." But there was a point, while living at Los Angeles' notorious Tropicana Motel(8), when the barfly image threatened to swallow him whole. Dissolution and the big nowhere beckoned. "Oh sure, it's inevitable, y'know? When you begin, it's a man takes a drink. When you end up, it's a drink takes a man. Keeping my balance during that period was tricky. When I was in my twenties, I thought I was invincible, made out of rubber. You skate along the straight razor and flirt with it all the time. I've been sober now for nine years; the best thing I ever did apart from getting married. Was it hard to quit? No, the hard part was before I quit. This is the easy part." He hasn't acted in a film for three years and doesn't know whether he ever will again, though he thinks the experience has allowed his songs to grow. "When you sing, you're kind of acting. The whole act of singing is like a big question you're asking, something you are reaching towards, wondering about or ranting over. In Alice there's a lot of images and reflections, like a fever dream or something. Songs are sometimes at their most satisfying when they confuse you - you don't listen to them for information. It's not like you read a recipe on a box of macaroni. If you listen to a song, you're asking to be confused or mystified. You're asking to go get lost." And, as the man says, sometimes that is the best way to find what you're looking for.

Notes:

(1) Alice and Blood Money: Alice (the play) premiered on December 19, 1992 at the Thalia Theater, Hamburg/ Germany. Further reading: Alice. Woyzeck (the play) premiered November 18, 2000 at the Betty Nansen Theatre in Copenhagen/ Denmark. Further reading: Woyzeck.

(2) Paul Auster's My Father Was God: "I Thought My Father Was God: And Other True Tales from NPR's National Story Project", Publisher: Henry Holt and Co.; 1st ed edition (September 13, 2001) ISBN: 0805067140. Publisher paperback: Picador; 1st Picador USA paperback ed edition (September 7, 2002) ISBN: 0312421001. Further reading: Paul Auster website.

(3) Mel Clay's strikingly titled Jazz-Jail And God: "An Impressionistic Biography of Bob Kaufman by Mel Clay Mel Clay's book on Bob Kaufman . . . is a work which answers the unique call of Kaufman's own -duende- inspired vision, giving back to the Poet & to the reader the Poet's life as a Poem. The book is as much poem as Biography and Mel gives us tight language running riffs of what we used to call "the real jingo" (as in lingo), making all the necessary ganglionic synapse jumps which lead us to hallucination and inspiration. Third Rail, Ira Cohen." Impressionistic Biography, 108 pages. Photographs and bibliography. ISBN 1-879594-12-9.

(4) The Worlds Of Charley Patton CD box set: "Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton" [Box Set]. Audio CD (October 23, 2001). Original Release Date: October 23, 2001. Number of Discs: 7. Label: Revenant Records. ASIN: B00005QD75.

(5) The last time I interviewed Waits was in 1985: "Hard Rain", New Musical Express magazine. Gavin Martin. October 19, 1985

(6) A landmark $2.4 million lawsuit against Frito Lay: Further reading: Waits vs. Frito Lay

(7) The Black Rider: The Black Rider: The Robert Wilson/ Tom Waits play premiered March 31, 1990 at the Thalia Theater, Hamburg/ Germany. Further reading: The Black Rider.

(8) Tropicana Motel: Further reading: Tropicana Motel.