|

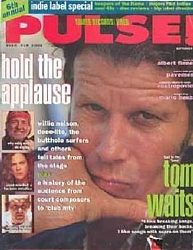

Title: Composer, Musician, Performer, Actor - TOM WAITS Is A Renaissance Man Whose Musique Noir Captures The Sound Of The Dark Age Source: PULSE! magazine (USA), by Derk Richardson. Photography by Christine Alicino. Thanks to Larry DaSilveira for donating copies Date: Rinehart's/ Petaluma. September, 1992 Key words: Bone Machine, Elvis Presley, Machinery sounds, Experimental instruments, Creative process, Kathleen, Keith Richards, Voice, Black music, Filmography Magazine front cover: Photography by Christine Alicino (?) |

Composer, Musician, Performer, Actor - TOM WAITS Is A Renaissance Man Whose Musique Noir Captures The Sound Of The Dark Age

"What I like to try and do with my voice is get kind of schizophrenic with it and see if I can scare myself."

Tom Waits is stirring his third cup of coffee, pouring in the creamer from one of those little plastic thimble-like containers. Outside this truck-stop cafe, just off Highway 101 in Petaluma, the Northern California drought has taken a rare day off and a steady summer rain is falling on 18-wheelers, Ford pickups and Waits' faded gold 1964 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. It's 4:30 in the afternoon and Waits, after half an hour of conversation, is just warming up to the task of doing his first interviews in nearly five years and talking about his new album, Bone Machine (lsland/ PLG), his first studio album of songs since 1987's Franks Wild Years. "I don't like to be pinned down," he mutters in the unmistakably gruff voice that has grown increasingly graveled and ravaged on record since his 1973 debut Closing Time. "I hate direct questions. If we just pick a topic and drift, that's my favorite part."

Glancing around the diner, where truckers are wolfing down pork chops and making calls from the red leatherette phone booths. Waits notices the clocks-on one, the hands sweep across the face of John Wayne; the other's face is that of Elvis Presley. The young, healthy, "Love Me Tender" Elvis. "I went to Graceland," he says in his rumbling whisper. "I had to pull away from the crowd about half way through. My little boy said, 'Hey why don't we dig him up and take his teeth out and make a necklace.' A lot of people on the tour act like they're seeing the place where Christ lived and they don't like to hear things like that. But I got a kick out of it. There was a bullet hole in the swing set where his kid used to play. I didn't like that; that was a little rough. A bullet hole in the slide. Even the way they discussed that aspect of it, it was like, 'Oh the boys, they were just having fun.' But you know what the scene was like-they were all liquored up and opened the back door and someone got the carbine 410 and they had to shoot at something or they would've hit a neighbor, so they said, 'Try for the swing set.' The trip was a little rough that way.

"But it was a good eyeball on our country," he continues. "It has a hollow center, like those Valentine candies with a hollow center. Whoa. It was very much like a sideshow, and I'm always curious about those things-you know, two-headed cows and stuff like that. Forget about it; I'm there. I don't care what it costs. I'll pay, I'll go in, sit down. I'll see the three-headed baby and all that stuff(1). When I got it on that level, it made better sense."

Anyone familiar with the evolution of Waits' music has a sense of his fascination with society's underbelly and the modem legacy of broken American dreams. Such concerns have long since marked his output, from the introspective, bohemian singer-songwriter folk of his "Old '55" (covered early by the Eagles) and "San Diego Serenade" (recently recorded by Nanci Griffith(2)), through the sleazy "Pasties and a G-String" /"Warm Beer and Cold Women" nightlife world of Small Change and Nighthawks at the Diner, to the sometimes murky and clangy, musically complex, urban soundscapes of Swordfishtrombones and Rain Dogs (commonly regarded as the first two parts of a trilogy with Franks Wild Years). As well, Those preoccupations resonate in Waits' live performances, especially his theatrical Big Time tour of 1987, his film roles (see sidebar), his film scores (most recently for Jim Jarmusch's Night on Earth) and his choice of material for a variety of tribute compilations-including "Heigh Ho" for Hal Willner's Stay Awake Disney roast, Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht's "What Keeps Mankind Alive" for Lost in the Stars, and an ironic "It's Alright With Me" for Red, Hot + Blue. "I like things that are kind of falling apart," Waits says, "'cause I come from a broken home, I guess(3). I like things that have been ignored or need to be put back together." With Bone Machine, Waits takes everything-the themes and the sounds of breakdown and decay-to new extremes. The portrayals of judgment day, rural desolation and various forms of betrayal, the rattling percussion, the grinding guitars, the wheezing saxophones and keyboards, and Waits' hoarse bellowing and sinister whispers flesh out the songwriter's vision of heaven/hell. "I have some new categories," he says. "The end of the world, that's kind of a new category for me. Suicide notes(4). Murder. "The Earth Died Screaming'-that's one of my favorites; it's got kind of an apocalyptic, I don't know, African thing." You can picture Waits, in his boots, jeans and black leather jacket with a big rip under the left arm, rummaging through the rubble of a suburban neighborhood ravaged by the big earthquake or the nuclear holocaust. He's poking at things with a stick, looking for metal shards and bits of broken machinery that only he would salvage, whacking them to make them confess their innermost feelings.

"We're like bone machines," he says of the album title. "Most machines take on a certain kind of human quality, even a bicycle, particularly an old bicycle that's been ridden a lot, even when no-body's on it. I like that aspect of machinery. I saw a picture of a bottle making machine and a guy working it, back in the '20s. It made like 40,000 bottles in like 12 hours, and there was something very human, something very animal about it; it looked like some kind of creature with the skin burned off. I like those sounds. I wanted to explore more machinery sounds."

So Waits commissioned a percussion rack called the Conundrum(5). "It looks like some kind of perverted giant Spanish iron cross or something." The results include "In the Colosseum," which sounds like someone's hammering and clamoring in the next room, and "The Ocean Doesn't Want Me," a Ken Nordine-meets-Sea Hunt recitation about a foiled suicide attempt, haunted by the muffled clang of a giant iron chain knocking against an underwater pier.

"On 'The Earth Died Screaming,' we got sticks and we tried them everywhere," Waits says. "I wanted to try and get some of that sound of pygmy field recordings that I love so much, and we couldn't get it. We tried different places in the room, different microphones, nothing. Different kinds of sticks, sizes of sticks. And then we went outside and just put a microphone on the asphalt and there it was, boom, 'cause we were outside.

"I'm exploring more and more things that make a sound but are not traditional instruments," he continues. "It's a good time to do it, too, because there's a lot of garbage in the world that I can use that is just sitting out there rusting. I can't believe it. I think something is gonna come out of this garbage world we're living in, where knowledge and information are becoming so abstract and the things that used to really work are sitting out there like big dinosaur carcasses, rusting. Something's gonna have to be made out of it that has some value. What can we do? Bury it and live on it? Americans still have some sense of, 'What can I do with this now that it's no good anymore besides just leaning it up against the barn?'

"I've heard that trash day in Japan is pretty wild, if you want to pick up some pretty weird things that have become obsolete in just the last seven or eight days. So I think about those things. I go up and hit stuff a lot to see what it sounds like. Getting it to make sense in the studio is always something different - how it's miked, what kind of room it's in. You're always up against the physics of it. I'm interested in that. I get into absurd arguments with myself about sound and the texture of it, all these things that keep you up at night that just drive you nuts, which is why I'm glad that this record's finally gonna be released: Get it out of my house! But I love the process, I really do. I like having music going through my fingers."

One of the dinosaurs Waits reclaimed on Bone Machine is the Chamberlain(6), a pre-synthesizer key-board that taps into analog tape loops of pre-re-corded material. "It's stunning, really," he enthuses. "I have like 70 voices on the instrument, from horses to rain, laughter, thunder, seven or eight different trains, and then all the standard orchestral instruments. It's a good alternative if you don't like the sound of the more conventional state-of-the-art instruments-sometimes it's like they've had the air sucked out of them."

Most of the music on Bone Machine is, appropriately, stripped down to guitar and percussion, predominantly by Waits, with Larry Taylor (Jerry Lee Lewis, Canned Heat) on upright bass. Waits is self-deprecating about the extraordinary array of guitar sounds he has generated. "Actually," he says, "I had somebody else doing it and I paid them. I said, 'Well, listen, I'm not gonna use your name; do I have to pay you a lot more so I can say it was me?' And in a lot of cases they said that I could do that: 'Just pay me off and I'll disappear, and there'll be no suit or anything.' I can play guitar in a limited spectrum, but I can play anything within a limited spectrum. It's like if the leg of the chest of drawers is broken off, I can get four books at just the right height so it won't fall over. I can be those four books with a song. I can't be the chest of drawers but I can be the four books.

"And a lot of times, that's what you're doing in a song. You're listening and thinking, 'What does it need?' Some of what goes into song-building is almost a medical Frankenstein process. What does it need? It's very beautiful but it has no heart, or it has nothing but heart and it needs a rib cage, or what-ever. I'm usually good at the medical questions about music. Eventually I'll probably just be a medical consultant in music. I'll be called in to look at sick songs and I'll either say, 'Put the sheet over it,' or, 'Operate.' I'll have a little bag with my saw. Sometimes you have to break the leg and then reset it. I'm good at that. But it's painful. But if you didn't call me in early and you need me now, you gotta be willing to go through some discomfort. I like breaking songs, breaking their backs. I like songs with scars on them - when I listen to them I just see all the scars."

Instead of forming a band to fit the surgical needs of his new songs, Waits invited his favorite musicians to make guest appearances: saxophonist Ralph Carney, bassist Les Claypool from Primus, the Limbomaniacs' Brain on drums, guitarists Joe Gore (also senior editor at Guitar player magazine), David Philips and Waddy Wachtel, David Hidalgo from Los Lobos on accordion and violin, and, on "That Feel," co songwriter Keith Richards.

"If I had started out in a band, if I was a band, I would have already broken up," Waits laughs. "But I've had great musical impulses and experiences with many people. I'm not a real gregarious type of person where I'm like some kind of magnet so that people are brought into my gravity. Although it would appear that music has a more social aspect than maybe bug collecting, people are still isolated regarding their own peculiarities. I venture out there very carefully and then have to shut my mouth a lot. But when you meet someone you have a rapport with, it's really thrilling. I like it when you soar after a session-your knuckles are bleeding and your butt hurts, you've got skinned elbows and knees, and your pants are wet and you've got blood in your hair. I consider that really great. It's not always the case but you hope for that, you work for that. The responsibility to whatever you're doing requires that you do take yourself into those kinds of configurations in order to remain some kind of meaningful antenna and to stay filled with wonder about it all."

If Waits had let himself go completely, he says, Bone Machine might have turned into a total experiment in sound. But in the process of putting it together, the album was taken over by the themes of the songs. That didn't make his work any easier, however. He waxes on at length about the struggle to bring new songs into the world. About half of them were co written with his wife, Kathleen Brennan. "Kathleen and I went into a room for about a month and banged 'em out," he says. "We started with nothing sometimes. One on one. It's a different kind of thing, writing songs with someone. But hey, we got kids together, we can make songs together. I fall into a groove too easily. I get in there and say, 'Oh, here's my place." It's like a shovel handle. Even on the piano, my hands are at the same place every time, because your hands have an intelligence that's separate from your own. But sometimes you need somebody to say, 'No, put 'em over here and try this,' and she does that. She calls me on all that stuff. 'Oh, this again, oh Jesus! Oh, here's the hundredth one of those.' But, oh yeah, I beat her up, too. Not literally," he says, leaning into the tape recorder. "I don't really beat her up, don't misunderstand me."

Waits describes the agony he puts his songs through "Some come out of the ground just like a potato," he says. "Others, it's like papier-m�ch�: I gotta get the flour out, I gotta get dirty, and it makes you mad. With some, it's like the good son 'Proud of you son,'" he says in Jack Nicholson's The Shining voice. '"You've always been a good son. You, on the other hand, have always given me problems, you won't be going on our little trip east.'

"I get real cranky about the songs," he says, "I get mad at the songs. 'Oh, you little sissy, you little wimp, you're not gonna go on my fucking record, you little bastard. No way are you going, and we're leaving in about three days and you're not going with us, 'cause you're a sissy and a wimp.' And then songs start to get like, 'Oh, god, we can't go.' Toward the end it's always good to whip the songs a little bit, scare 'em, and then make fun of them. And then they change. You come back the next day and they're better-behaved.

"You know who really does that great?" Waits asks rhetorically. "Keith Richards. He's real like voodoo about it. He circles it. He's like an animal, smelling it, kicking dirt on it. He's real ritual about it, real jungle. I had an experience writing with him for several weeks and it was really thrilling. He's written so many different kinds of songs. You identify him with that really dirty guitar and that gang-like stance, like a killer at a gas station- 'Oh man, we better not stop for gas here'-and then you realize he's a real gypsy. We had some wild times. You can't drink with him-just forget about it, you'll be leaving early, he reduces you to something very embarrassing. You'll be the table- they'll put drinks on you. He toughens you up."

After spending the past five years on special projects, including the soundtracks, guest shots on word-jazz maestro Ken Nordine's Devout Catalyst and saxophone legend Teddy Edwards' Mississippi Lad, and a joint-effort operatic piece. The Black Rider(7), written with William Burroughs and Robert Wilson (staged in Hamburg, Germany, where he'll do Alice in Wonderland(7) with Wilson, as well). Waits may have needed to toughen himself up a little bit to face down those songs. "If you're writing for film," he says, "it's all collaborative and sometimes you're like part of an orchestra, you're the trombone, you're the percussion, or whatever. You're the pallbearer, that's what you really are! Most films and most records are like the tombstone beneath which is buried the real film or the real record. It's amazing how much of the project ends up buried-ideas that you had, things that could have happened but didn't, songs that didn't make it. You hope that in dragging it out of the hole, you don't tear its head off and you're left with fur. It's rough for me."

But what he loves about writing songs, he says, is the opportunity they afford for tinkering. "You can change everything if you want," Waits says. "If you don't like the way something is going, you can totally change the bone structure of a song, or three or four songs in the way they all work together. The thing I hate about recording is that it's so permanent. Ultimately you have to let it dry, and I hate that, 'cause I like to just keep changing the shape of 'em, and cut 'em in half and use the parts that I didn't want on that one on another one.

"That's the part that drives everybody crazy. I like to get in there with the songs and eat them up and push them around and explore all the variables. Sometimes it sounds Irish and then you tilt it a little bit this way and it sounds more Balinese and over here it sounds more Romanian. I like that part of working with music; you can find yourself in a different latitude and longitude. There's a lot of different coordinates for rhythm, and when you start exploring rhythms, you find that maybe it sounds Chinese, and then you realize it's just kind of like banging sticks on the ground, it's just something that comes naturally and you don't necessarily have to put it in a particular country. Some of these things come out of your own rubber dream."

Over the years. Waits has grown more confident about his ability to bring what he hears in his head into being as music. "I like to think wherever I aim this thing, I can hit it," he says. "You get to where if you really know how to shoot it, you can pick anything off. But a lot of songs don't want to be caught, and they do get away. If you want to take them alive, you have to have something other than a conventional understanding of music. It's like anything else-what you put yourself through in milking it is what comes back to you, in direct proportion."

Then there's the issue of his voice, which he has disciplined and sometimes processed, with megaphones and other devices, into an extraordinarily expressive, if harrowing, vehicle. "What I like to try and do with my voice is get kind of schizophrenic with it," he explains, "and see if I can scare myself or go from one song to the next and see if I can like turn my head around on my body so my vertebrae cracks. Or I put on lipstick and start screaming into a tin can. Oh, yeah, I'm happy with my voice as an instrument. I quit smoking and nobody noticed. Or I say, 'I lost my voice, I have no voice,' and they say, 'I didn't notice.' That really hurts."

Finally, after improvising at length on the riffs about the blood and bones of songmaking. Waits leans into the corner of the booth and tries to place himself in the overall picture of American culture, a picture that doesn't have much room for someone who likes to walk into his neighbor's yard and bang on things. "It's hard sometimes if you're faced with having to deal with the traditional world of commerce," he says. "We seem to salute anything that you can make 10 million of and sell to everybody; the fact that everybody's got one is a triumph, not the fact that you made 10 great ones. I don't use that as a gauge.

"But there are parts of America where music is a living thing. In New Orleans, music is just like this Tabasco here. They just go get some and put it on their food. The only thing really vital in this country, that is constantly evolving and working very hard, the only real American music is America's black music. It's infused with something so important. My daughter listens to the rap station and it's a music that is like graffiti or jail poems, it's like a brick through the window. It's powerful and essential."

For Waits, making a culture of his own in the vast wasteland of middle America has been an ongoing project much like composing songs. "For me, white boy from California," he says, "I listen to things and break a piece off of this, and a piece off of this, and I tie this to that, put these two together and then I take them out to meet the pieces coming down from the top and wrap it all in newspaper and set it on fire. It's like making a record," (or maybe like doing an interview?), he concludes before driving off in the rain that nobody expected. "You don't really finish, you just stop. You just keep painting it and doing things to it and eventually you have to stop."

Sidebar:

Lifting Waits Portrait of an Artist as a Matinee Idol

"You're a good DJ; all you have to do is learn how to jerk people off a little- that's all they really want," says Ellen Barkin to Tom Waits' gruff Zach in the 1986 film Down by law. "I never jerk people off and you know that," he replies. If anything captures the Waits aesthetic, it's that classic moment in his breakthrough film as an actor. Directed by Jim Jarmusch, Down by Law stars Waits as a misunderstood drifter set up for a crime he didn't commit and sent to a New Orleans parish prison with two other unfortunate misfits (Waits' voice is also heard as the DJ in Jarmusch's Mystery Train). Since this is a Jarmusch movie, attitude and appearance are everything - and that's exactly what Waits delivers. He plays himself - coarse, edgy, speaking with a slur - a colorful character actor to those outside the music world.

Waits' film accomplishments have been a steadily growing side job. Usually he plays bit parts: He was cast for his musicianship in his first role, in Sylvester Stallone's 1978 opus, Paradise Alley, and for his scrappy, disheveled nature in last year's The Fisher King(8), where he played a wheelchair-bound vet who offers Jeff Bridges a few unsound words of advice. Many of Hollywood's director-elite are attracted to Waits' off-kilter sensibilities, often bringing him back for subsequent films. Francis Ford Coppola turned Waits into a recurring player in his early-'80s films after Waits delivered an Academy Award-nominated score for the director's noble failure, One From The Heart. Coppola cast Waits as the owner of a smoky barroom dive on the edge of town in The Outsiders (1983) and in Rumble Fish (1983), and as a nightclub manager in 1984's The Cotton Club. Waits will next appear in Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula, due out at Thanksgiving.

Acclaimed director Hector Babenco also took a liking to Waits' surly presence and gave him two of his most challenging acting roles to date. In Ironwood (1987), based on William Kennedy's Pulitzer Prize winning novel, Waits is Rudy, a Depression era bum who learns he has cancer and just a few months left to live. Playing opposite veterans Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep, Waits hits an acting high. He holds his own with the always scene-stealing Nicholson and even gets some bittersweet mileage from his character.

In Babenco's At Play in the Fields of the Lord (1991), Waits is a grizzled bear of a pilot who wants nothing more than to get back to civilization after being trapped in the South American jungles. Though his role doesn't add much to the already convoluted nature of this three-hour-plus failed epic. Waits is a shining light in an otherwise tepid drama.

While Waits tends not to stray too far from roles that are reflections of himself, he does dabble in filmic extremities. In the broad farce Cold Feet, he got his first chance in a leading role opposite Keith Carradine and Sally Kirkland. Playing a ruthless murderer with a penchant for Turkish figs, he gives the sometimes over-the-top character of Kenny an undeniable charm. His darkly humorous nature saves this film from being a washout.

Waits plays a similar derelict in Queen's Logic. As Monte (he wears gaudy clothes and buys a Monte Carlo every year because of his name), he's the outsider friend to the film's core group of '70s nostalgia-starved big chillers. His scenes are sparse, but are some of the film's best.

Casting against type, 1988's Candy Mountain gave Waits a juicy little part as the wealthy, golf-playing brother of a legendary luthier who's being sought by the film's main protagonist. The cast is filled with other rock luminaries, including Joe Strummer, Dr. John, David Johansen (aka Buster Poindexter) and Leon Redbone.

Perhaps the test of Waits' durability was his 1988 concert film Big Time, in which he used filmed material as a clever framing device for his onstage musical theatrics.

"On the outskirts, I'm a restless person," says Rudy in Ironweed, and though Waits provides mainly local color in his movie roles, he's used his one-of-a-kind persona and restless nature to secure a niche - without once jerking off his audience.

Anthony C. Ferrante

Notes:

(1) I'll see the three-headed baby and all that stuff: as later mentioned in "Lucky Day Overture" (The Black Rider, 1993): "Ladies and gentlemen Harry's Harbor Bizarre is proud to present Under the Big Top tonight Human Oddities! That's right, you'll see the Three Headed Baby You'll see Hitler's brain."

(2) Recently recorded by Nanci Griffith: "Late Night Grande Hotel", Nanci Griffith, 1991 Label: MCA Records, MCAD-10306. Song covered: "San Diego Serenade"

(3) Cause I come from a broken home, I guess: refering to Waits's parents divorcing when he was 9 or 10

(4) Suicide notes: refering to "The Ocean Doesn't Want me"

(5) Conundrum: Percussion rack with metal objects. Made for Waits by Serge Etienne. Further reading: Instruments

(6) Chamberlain: Should be spelled "Chamberlin". The Chamberlin was the original US keyboard instrument from which the Mellotron was copied, designed by Harry Chamberlin in the USA during the 1960's. The Chamberlin used exactly the same system as the Mellotron for playing back tape samples yet had a sharper more accurate sound. Compared to the Mellotron, the Chamberlin is a bit harder to play, requiring a rather heavy and consistent hand on the keys. Further reading: Instruments

(7) The Black Rider/ Alice: further reading: The Black Rider. Further reading: Alice

(8) The Fisher King: Fisher King, The (1991) Movie directed by Terry Gilliam. TW: actor. Cameo as disabled veteran. Interviewer: In The Fisher King, Tom Waits puts in a really memorable performance. I've been a fan of Tom for ages. It was a real shock to see him since he wasn't credited. How did Tom get involved? Terry Gilliam: He was a friend of Jeff Bridges, basically. He said, "You ought to meet Tom". It's funny because when I met him and even in the course of making the film, I'd never heard a Tom Waits record. I'd never listened to them at all. I just met him and liked him immediately. So into the film he went, and he was great. The studio was trying to cut him out. They felt it wasn't advancing the narrative in any significant way so they thought that was things that could go. They were totally wrong. (Source: "Dreams: December 1997 interview with Terry Gilliam Edited by Phil Stubbs).

- Transcript: NY station hall. Jeff Bridges as DJ Jack Lucas. Tom Waits as disabled veteran in wheelchair. Legs hidden. Holds cup which says "I love NY". TW: Did you hear Jimmy Nickels got picked up yesterday? JL: Oh yeah? TW: Yeah, he got caught pissin' on a bookstore. Man is a pig. No excuse for that! (woman throws coin in cup ) TW: Thank you babe. We're heading for social anarchy when people start pissin' on bookstores. (man throws coin next to cup ) JL: Asshole. Didn't even look at you. TW: Well, he's paying so he don't have to look. You see, the guy goes to work every day. Eight hours a day, seven days a week. He gets his nuts so tight in a vice he starts questioning the very fabric of his existance. Then one day by quitin' time, boss calls him into the office and says: "He Bob! Why don't you come on in here and kiss my ass for me will you?" Well, he says: "Hell with it! I don't care what happens. I just want to see the expression on his face as I jam this pair of scissors into his arm." Then he thinks of me. He say: "Wait a minute! I got both my arms. I got both my legs. At least I'm not begging for a living." Sure enough Bob's gonna put those scissors down and pucker right out. You see, I'm much like a moral travellight really. I'm like saying: "Red, go no further! Boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie, boo-ie." (Transcription by "Pieter from Holland". As sent to Raindogs Listserv discussionlist. April 1, 2000)